The space in between

Decades ago, when a journal editor removed the term ‘nano’ from an article he had submitted, pioneering researcher Raoul Kopelman (1933-2023) was at a loss for words. The prefix, which is Greek for ‘dwarf,’ stands for one-billionth of a meter — or 10-9 — in the International System of Units. It was an accurate descriptor for the teeny, tiny particles at the heart of Kopelman’s study, but the editors feared readers wouldn’t know the term. They opted for ‘sub-micro’ instead.

As more scientists explored the field, those same editors eventually came to embrace the terms ‘nanoscience’ and ‘nanotechnology,’ which describe the ability to see and control individual atoms, molecules, or small clusters.Kopelman, who joined the U-M chemistry faculty in 1966, was less concerned with the label than the realm it described. Mostly, it was the space between those atoms, molecules, and clusters that really intrigued the scholar.

“Whole universes are in there,” he told Michigan Today just months before he died in 2023.

Let’s get small

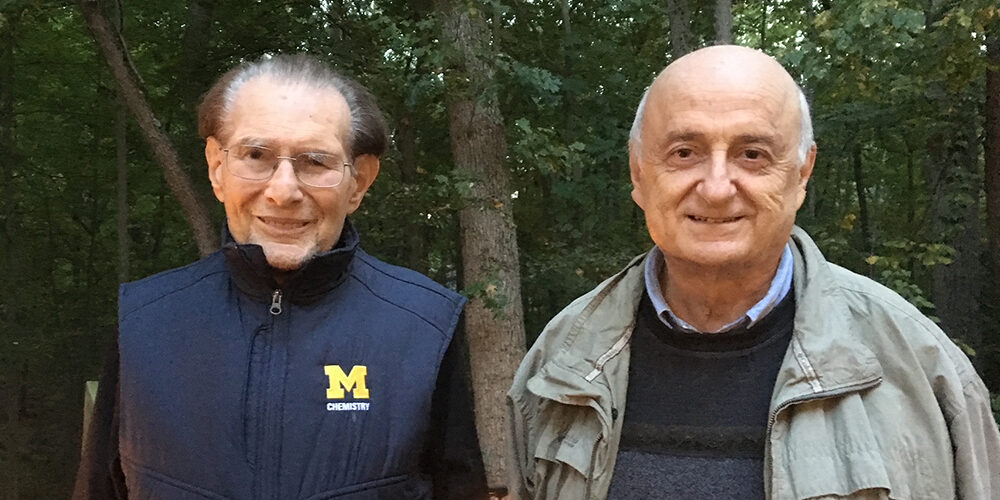

Kopelman and mentee Panos Argyrakis pose with a Kopelman Research Poster at the Chemistry Building, 2023. (Image courtesy of Shirli Kopelman.)

Some 57 years after he arrived at Michigan, Kopelman remained an active participant in ‘NanoWorld,’ advancing breakthroughs in precision medicine and developing interdisciplinary graduate-level courses in chemistry, technology, climate science, and artificial intelligence.

Research topics ranged from solid-state physics to biomedical engineering. All of his work was characterized by a rare focus on interdisciplinarity and most of it featured collaborations with treasured mentees who continue to have an impact in the industry; many are tenured professors at prestigious universities around the world.

Kopelman authored more than 700 scientific papers, patents, and books, and is perhaps best known for developing the Hoshen-Kopelman algorithm, a simple and efficient algorithm for labeling clusters on a grid, where the grid is a regular network of cells, with the cells being either occupied or unoccupied. The algorithm’s practical application is so widespread in modern technology that scholarly citations of the work pop up every single day on Google Alerts. Some 5,000 citations have appeared since publication of his 1976 paper “Percolation and Cluster Distribution. I. Cluster Multiple Labeling Technique and Critical Concentration Algorithm.”

The mentor’s journey

Argryakis leaves Kopelman’s office for the last time. A regular visitor to Ann Arbor since 1980, Argryakis often arrived at his co-author’s office with a vexing challenge to solve. (Image courtesy of Shirli Kopelman.)

In his final months, Kopelman was eagerly preparing for a reunion, on what would have been his 90th birthday, with more than 70 doctoral students and dozens of postdocs who had been trained in his U-M lab. Before arriving in Michigan in 1966, he was at the Technion (the Israel Institute of Technology), Columbia University, Harvard University, and Caltech. Four of his former students are Nobel laureates: Richard Smalley, Eric Betzig, Roald Hoffman, and Arieh Warshel.

One of his closest colleagues and former students, Panos Argyrakis, PhD ’79, had been visiting his mentor and longtime co-author twice a year since 1980. Argyrakis is a professor of computational physics at Greece’s University of Thessaloniki. It was Kopelman who set Argyrakis on that path five decades ago as together they discovered the nascent technology of computer modeling.

Converting data from analog to digital in the early days (using a computer that consumed the entire floor of a university building) offered a scientifically robust method to analyze, corroborate, and advance Kopelman’s research. He was working with lasers in the ’70s and when Argyrakis demonstrated an aptitude for computational modeling, Kopelman seized upon his mentee’s skills.

“He realized early on that I was better at calculations than doing measurements in his lab,” Argyrakis says. “I was able to study the same systems as Raoul, but computationally, rather than from the lab bench.”

A glass half full

In October 2023, Michigan Ross professor and Raoul’s daughter, Shirli Kopelman, curated and hosted a memorial symposium to celebrate her father. Stellar Multidisciplinary Research hosted more than 100 of Kopelman’s mentees and colleagues; they spent the day reflecting on the scholar’s research impact, which transcended academic disciplines, inspired entrepreneurial and institutional innovation, and contributed to the public good.

“Raoul was competitive but collegial, a ‘glass-half-full’ guy,” said Betzig, co-recipient of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. “Today’s medical molecular cancer research is an extension of Raoul’s original idea.”

Betzig is a professor of molecular and cell biology, the Eugene D. Commins Presidential Chair in Experimental Physics, a Senior Fellow at the Janelia Research Campus, and Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at the University of California, Berkeley. His mentor inspired an ability to move between fields as he made publishable, important contributions in multiple areas.

“Raoul had an immense imagination and sought impact in everything he did,” Betzig said.

That imagination allowed Kopelman to reinvent himself as he investigated new areas, said Theodore Goodson III, the Richard Bernstein Collegiate Professor of Chemistry at U-M.

“No matter what we were going to talk about — the theory of excitons or some applications about biomedicine — I knew that when I walked out of the room a couple of hours later, we would have some kind of solution to the problem,” Goodson said.

Mad skills

Argryakis would arrive at Kopelman’s office with data recorded from his computer in Greece. The label on this early version of a flash drive reads “ZEUS1.” (Image courtesy of Shirli Kopelman.)

Argyrakis, a scholar of theoretical condensed matter physics, remembers using his prehistoric computer in Greece in the early ‘80s. At the time it was considered cutting edge and small, considering the early ’60s version took up an entire room. Before trekking to Ann Arbor, Argyrakis would transfer his data onto a hard floppy disc the size of a vinyl record album that “weighed about 10 pounds.” Much of his work with Kopelman revolved around particle systems and diffusion, dubbed the “random walk.” The phenomenon exists throughout nature, from single atoms to entire galaxies. The duo co-authored numerous papers on the topic as Kopelman successfully attracted funding to continue.

“Raoul was among the top faculty for bringing money to the chemistry department, which at times was very difficult,” Argyrakis said. “One of his biggest satisfactions was to pursue groundbreaking, high-impact research and at the same time, guide his students to become independent thinkers.”

Kopelman’s determination could not be contained, even as heart issues and other medical conditions temporarily affected his movement and eyesight. U-M’s Xueding Wang, the Jonathan Rubin Collegiate Professor of Biomedical Engineering, was co-writing a proposal with his colleague when he suggested they defer until Kopelman was in better health.

“Raoul said, ‘Why? I still have one hand that can type. I still have one eye that can look at the screen.’ So we worked on it together — and we got funded,” Wang said.

Kopelman’s energy wasn’t all about academics, though. He placed an equal emphasis on social discovery. He was known to invite students to live with his family as needed and opened his door for dinners and other casual interactions.

“He treated everyone like a big family and you got to see how scientists really worked, what they really thought,” said Eric Monberg, PhD ’77, of Optical Fiber Research.

“Raoul was a model mensch,” said Rachel Goldman, Maria Goeppert Mayer Collegiate Professor, U-M professor of materials science and engineering, professor of physics, and associate director of the Program in Applied Physics. She had planned to invite the scientist to join the department’s advisory board before she learned he had passed away.

In an editorial published in ACS Sensors, “Remembering Raoul Kopelman (1933–2023),” Heather Clark, PhD ‘99, described her mentor’s unique approach to science and his genuine kindness as a person.

A mentor’s legacy

Argryakis and Kopelman met in the late ’70s when Argryakis was pursuing his PhD. They remained friends and collaborators for life. (Image courtesy of Shirli Kopelman.)

It’s mind-boggling to consider the dramatic progress in the field of computing since Kopelman first recognized its potential. In the 1960s, he advocated the use of computing in the chemistry department, despite detractors who dubbed the effort “anti-educational.” Even so, he introduced the use of computer punch cards in his undergraduate lab course in physical chemistry. In 1977, while serving on the Rackham Graduate School Executive Board, he proposed that PhD students write and print their theses using the university computer. The faculty were dubious.

Argyrakis, though, was up to the challenge. He’d spent so much time in the university’s computer lab on Kopelman’s behalf that he’d befriended the author of a rudimentary, experimental, and text-only word-processing program. To locate the cursor, the user twirled knobs to control a vertical and horizontal hairline until they intersected, because the mouse had not been invented yet. Printing a huge document that complied with the university’s stringent doctoral standards wasn’t easy, but in 1978, Argyrakis became the first doctoral candidate at Michigan to write and print his entire thesis using a computer.

At the symposium in 2023, Argyrakis had tears in his eyes when he spoke: “Raoul was an integral part of my life for 50 years minus three months. He was always there to encourage, to offer his empathy at difficult times, and help to elevate one’s spirits. With his acumen, he offered himself and all his resources to that purpose.”

Fantastic

From 2003-23, there were two “Professor Kopelmans” at the University of Michigan: Chemistry’s Raoul Kopelman and Michigan Ross professor Shirli Kopelman. Father and daughter were good friends and close colleagues. (Image courtesy of Shirli Kopelman.)

In his final years, Kopelman focused on precision medicine, covering novel diagnostic and therapeutic techniques for cancer and heart disease. Implanting nanoparticles that precisely and specifically target and kill dangerous cells, the technology uses noninvasive and otherwise harmless red light, instead of high-energy lasers, X-rays, or gamma rays. With collaborators in U-M’s Medical School, Kopelman applied this technology to treat cancer and heart arrhythmia in rodents and sheep.

He may have been captivated by the nano, but Kopelman always favored the big picture. He preferred to focus on the future instead of the past — unless he was reflecting on his early childhood in Israel. His family had fled Vienna during World War II to escape the Nazis. They settled in Tel Aviv when Kopelman was five years old.

“I would stare at the night sky and could see galaxies beyond the Milky Way,” he said.

When he read Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea as a child, and later, The Fantastic Voyage by Isaac Asimov, Kopelman set his sights on the undiscovered and as-yet-unnamed world of nano. Asimov’s plot tracks a research crew reduced to a microscopic fraction of their original size, boarding a miniaturized atomic submarine and being injected into a dying man’s carotid artery.

“Raoul was as free-spirited as he was scientific,” said Robert Kennedy, U-M’s Hobart H. Willard Distinguished University Professor of Chemistry, Pharmacology. “His work was a fantastic voyage.”Metaphors like that tiny submarine inspired Kopelman throughout his career, said daughter Shirli Kopelman.

“He saw fractals where others saw trees,” she said. “His work will continue to light the path of future generations.”

(Lead image courtesy of Shirli Kopelman: Raoul Kopelman and his mentee/colleague Panos Argyrakis, PhD ’79, met twice a year for decades, continuing to collaborate until Kopelman’s death in 2023.)

Panos Argyrakis - 1979

Raoul has been an inspiration for me since my early days in Michigan in the 1970s. I have the best memories of all our interactions, both at the scientific and personal level; these are very sentimental moments for me.

Reply

Alan McLean - 2020

Dr. Kopelman had a unique approach where he empowered students to take leadership while guiding them to become independent scientists. I will forever cherish our conversations exploring new ideas and brainstorming how to operationalize them empirically. He was an amazing mentor we had and I miss him greatly.

Reply

Bob Kennedy

Raoul was the platonic ideal of a scientist. He was ever curious, energetic, bold, careful, and inclusive. I always learned something from talking to Raoul and found him uplifting because of his positive outlook and enthusiasm. He was also caring and never failed to ask me about my parents after learning was of them was ill.

Reply

Rachela Popovtzer - post doc 2008

Prof. Kopelman was not only an outstanding figure in academia, but also a deeply influential mentor. His brilliance, charm, and kindness left a lasting impact on all who had the privilege of learning from him. His guidance shaped my career, as well as the careers of many others, offering unwavering support and inspiring us to strive for excellence. His wisdom, generosity, and dedication were unparalleled, and his influence will remain with us for years to come. His legacy continues to guide and inspire.

Reply

Murphy Brasuel - 2002

Professor Kopelman was a brilliant mind and a caring mentor. As a graduate student in the 1990’s under his guidance I learned the creativity and critical thinking essential to contributing to progress in science. As important, I learned self-care, as Dr. Kopelman understood the pressure and stress experienced by his graduate students and would give us explicit permission for self-care when he noticed the need.

Reply

Heather Clark - 1999

Raoul was the type of mentor who let his trainees take the lead on their projects, and delighted in discussions over the resulting data. When I called down to his office (yes, we used phones with cords back then) to tell him I had results on a big project, I would immediately hear his footsteps in the hallway as he rushed down to see the data and go over the results. His love of science was infectious, and he passed that love of science on to decades of trainees.

Reply

Paras Prasad - Postdoc 1971-74

I could not have asked for a better mentor than Professor Raoul Kopelman, who contributed to my professor career in so many ways. He inspired me to think outside of the box and do what would make a difference. He also gave me the most valuable opportunity of supervising some of his students while he was on sabbatical. Raoul continued to give me valuable advice and guidance throughout my academic career.

Reply

Bob Kuczkowski

Raoul’s research was of great interest to graduate students. But also his charism. I recall an especially memorable visit to Raoul’s office one afternoon years ago. He enthusiastically shared the news that his group was learning to pull optical fibers into sub-micro-tips to focus light on nano samples. He got so excited that he had to take me to his lab to have a demonstration. This was in the early stages of his groups remarkable efforts that led to bio analysis applications in cells and disease.

Reply

Jeffrey Anker - 2005

Raoul Kopelman was a fantastic mentor: kind, thoughtful, inquisitive, enthusiastic, well balanced, and full of stories. His approach to science and life was inspirational to me, and I sorely miss him.

Reply

Irene Blandy - 2012

Professor Kopelman have always instilled the importance of curiosity and tackling challenges head on, as they are not roadblocks but just another beautiful path. I continue to apply your teachings to friends and family and am grateful for your positive impact in my life.

Reply

Peter Friedman - 1974 (PhD) and 1976 (postdoc)

I was Raoul’s 1st grad student and when I started he had only been at UM for just over 1 year and didn’t yet have a lab. What surprised me was that he immediately trusted my judgement in designing equipment and not micromanaging what I was working on. This is what led to me being an experimentalist and not being intimidated in taking on new challenges including moving into completely new fields over the course of my career. We have kept in close contact for over 50 years and for many years Raoul’s family was like my own extended family. His interest in his students was humanistic in addition to scientific and one could talk with Raoul in depth on almost any subject. He is greatly missed and I think of him often.

Reply

Eric Fauman - Undergraduate 1987

Dr. Kopelman was my honors undergraduate P Chem prof and honors thesis advisor and subsequently my coauthor on my very first scientific publication in 1988. When I visited him in Ann Arbor in 2022, 34 years later, we picked up right where we had left off. He was full of stories spanning the decades right up the present. I love reading everyone else’s positive recollections of their time with him.

Reply

Kerri Pratt

I always appreciated Raoul’s interest in my research endeavors and his congratulations when I had success. I think we connected over this, as my research does not fit squarely into a traditional field, but rather draws on many different disciplines to make progress on important questions. Specifically, my research involves taking complicated instruments to remote locations to learn information that could only be collected in the field, which I think spoke to his fascination with outside-the-box measurements and charting new and exciting types of science. During the pandemic, Raoul joined our efforts to communicate to local schools about aerosol transmission of SARS-COVID-2, and this showed his caring for the community and wanting to contribute as a team.

Reply

Andrew Ault

Raoul was always supportive of me as a young faculty member. He was truly curious about how different research topics and ideas from a variety of fields would merge together to push science and society in positive new directions. He was always happy to help or to discuss a new idea, as he cared about both the science, but more importantly, the people in science. I will always remember giving a few guest lectures on my research on Aerosols, Particles, and Particulate Matter in a new graduate-level course he developed and launched in the Winter of 2023, titled: “Nanochemistry: Nanomedicine, Nanotechnology and Climate Nanoscience”. The course surveyed the foundational basics of colloid science, the methods of developing nanochemistry tools, and applications in the fields of medicine, technology, and climate. Raoul would attend and participate with as many questions as the students, reflecting his innate curiosity and excitement for science itself and as a key for societal impact.

Reply

Brandon McNaughton - 2007

Professor Kopelman was a true one-of-a-kind mind. If you knew him, you knew his passion for science and life. I had the opportunity to join his lab in 2003 as an applied Physics PhD student. I eagerly joined the Kopleman Lab over others because of his authentic joy for the discovery and the development of new science. I became a scientist because I dreamed of working on projects with big societal impact… with other scientists who cared more about the impact of their work than the recognition they received — a trait that Professor Kopelman carried for the entire time I knew him. He spent his life peering into the unknown mysteries of our Universe and bringing forth truth and knowledge with an energy and fervor that will deeply be missed by all that knew him. For those in the Kopelman Lab, we have many great memories of deep discovery and nano adventures!

Reply

David Hanson - 1965

I encountered Raoul in the mid-1960s when I was a graduate student, and Raoul was a senior research fellow working in Wilse Robinson’s group at Caltech. The verb encounter came to mind subconsciously when I began to write this essay. I then thought, what do I really mean by that. So I looked-up / googled definitions. One – a hostile meeting. Another – to come upon an experience unexpectedly. Right on! How did my brain make that connection?

Meeting and working with Raoul was an experience! We focused on applying the concepts of solid state physics to molecular solids. We spent many evenings discussing my experimental results: what did they mean, how do we understand and build on them, what needs to be understood, what should be done next? This interaction produced a couple of publications and contributed to the foundation for my subsequent research.

Raoul came with a fantastic perspective. He had studied Quantum Mechanics with David Bohm, Group Theory with David Fox (who I later collaborated with at Stony Brook University), got has PhD at Columbia with Ralph Halford, and was a postdoctoral fellow with William Klemperer at Havard.

Raoul’s community of scientists even included a childhood friend, Joshua Jortner. In a Tel Aviv elementary school they developed a chemistry club together, and then Joshua, together with Stuart Rice, was among our competitors in molecular solid state research.

Because of Raoul and his wonderful wife, Chava, I learned more about the Holocaust – a little bit from them, they did not talk much about it, but then much later I discovered their postings on Portraits of Honor – Holocaust Survivors.

After the Caltech experience, our research interests diverged, but every year I was amazed, but not surprised, at Raoul’s accomplishments.

Reply

Elliot Bernstein - 1964 to 1967

I first met Raoul in 1964 when I was a second year grad student just joining Wilse Robinson’s group at Caltech. Raoul just arrived in the group as a senior research associate. During that second year in the GWR group we were getting fluorescence and IR data on pure and mixed crystals of benzene at 4.2, 2.17, and 77 K and comparing them to their gas phase values. Raoul and I would discuss our results and their interpretation 6 days/week and 12 -14 hours/day until we had a solid understanding of their meaning for molecular van der Waals systems. A manuscript would then be generated and then passed on to GWR for final approval. The lesson here dealt with how to do academic research and how to interact with colleagues; from planning a series of long, difficult, low temperature experiments, to finally understanding their results, and then to putting all this on paper for others to appreciate. During this time, we (Steve Colson, Dino Tinti, Raoul, and I) basically learned how to be professors and to cooperate to form a functioning “group”. Raoul was a central actor in this process: all of us eventually became professors at various academic institutions. And what a journey it was, with Raoul at its inception and as its leader, even this early in his career.

Reply

Iyad and Sandy Zalmout - 2008, 2012

Our family came to know the Kopelman family through Chava, Raoul’s resilient beautiful wife. We soon became close friends sharing valued time over brunch, childcare challenges, and friendships. As we all shared stories of previous lives, challenges, passions and academics, we came to know each other well. Raoul was a huge persona, that would share, guide and uplift. We value the time that he gave us, the advise that he share and above all the inspiration that he ignited. Raoul will be missed, but his impact is long lasting and touched so many. Thank you Kopelman family for sharing Raoul and Chava with us.

Reply