An island under ice

What is it about Greenland that tickles the acquisitive spirit?

After all, it’s a pretty desolate place. Some 80% of its 836,000 square miles is covered by glacial ice to a depth of 10,000 feet. Maybe 1% of the ice-free territory accommodates human settlement.

But the Vikings wanted Greenland and settled it for a while. So did their descendants, the Danes and Norwegians, who tussled over it until Denmark was awarded sovereignty in the mid-20th century. And the native Inuits, who were granted self-rule in 2009 (with Denmark still in charge of foreign policy and defense), figure it’s been theirs since their ancestors arrived about 2,500 B.C.

Whatever instinct makes people want to claim a piece of the world’s largest island, it certainly animated William Herbert Hobbs, professor of geology at the University of Michigan from 1906-34.

A century ago, Hobbs led three U-M expeditions to study the weather high above Greenland as well as its sprawling ice pack. But he also planted U-M names all over the land mass — or tried to, at least.

Prone to argument

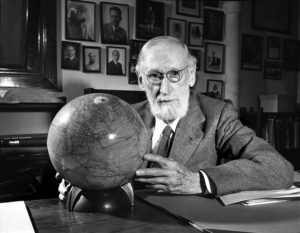

William Herbert Hobbs in his office in the Department of Geology. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library)

A wiry, bearded man of fierce energy, Hobbs went questing to both poles, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Central America to study how mountains and glaciers are born and sculpted by time and weather. He built U-M’s geology department nearly from scratch. He was both a rugged mountaineer and a sociable host who wined and dined the rich and famous at his Ann Arbor home — and he never hesitated to drop their names. He was a hawk for military preparedness and bitterly opposed President Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations. His hard edge offended many a colleague. One of them remarked that Hobbs’ “proneness to argument often brought down violent storms on his head.”

In the 1920s, well into his 60s, Hobbs set his sights on Greenland.

His purpose was to study the connections between polar glaciers, the weather, and the land masses beneath the ice. He planned a series of expeditions, all conducted under U-M’s aegis but with private funding. The first, in the summer of 1926, would lay the groundwork for the ones to follow.

From Nova Scotia, Hobbs sailed on a fishing schooner with a party of five — another U-M geologist, two meteorologists, a surveyor, and a radio man. They maneuvered through “many fleets of icebergs” and thick fog to a spot on Greenland’s southwest coast 25 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

Hobbs now showed he was either homesick or eager to court favor at home.

Presidential range

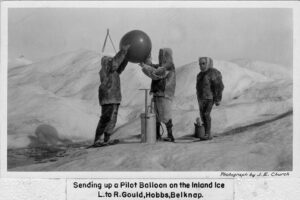

The scientists prepare a weather balloon for an ascent from Greenland’s inland ice, probably at Camp Mortimer E. Cooley. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library)

The little group had barely set down their gear when Hobbs set off on a spree with a map and a pencil, planting Michigan-connected names on practically any feature of the landscape that caught his eye.

To the expedition’s base encampment, he gave the name Camp Clarence Cook Little to honor Michigan’s president. (This may not have been the shrewdest public-relations move, since Little was already making himself unpopular in Ann Arbor for his autocratic style, not to mention his support for eugenics, birth control, and Prohibition.)

Soon Hobbs sent a party 100 miles inland to make a camp for the release of weather balloons. This second camp he named for Mortimer E. Cooley, the longtime dean of Michigan’s College of Engineering.

Back at Camp Little, he gazed out at a broad inlet and dubbed it University Bay. Then he surveyed the icy peaks that circled the bay and slapped on names to honor the five U-M presidents before Little — Mount Tappan, Mount Haven, Mount Angell, Mount Hutchins, and Mount Burton.

Mount Tappan rose from a great stone buttress that Hobbs named for Stevens T. Mason, the “boy governor” of Michigan who oversaw the University’s beginnings in Ann Arbor. Then, never one to overlook an anonymous buttress, he named the bulk under Mount Burton for Alfred Henry Lloyd, the professor of philosophy who served as interim president between Burton and Little.

Of mountains and lighting fixtures

A sketch of Hobbs in heroic-explorer mode, with sled dogs. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library)

The tallest mountain in one sector already had a name given by the Inuits — the Pingo. But a mountain next to the Pingo had no name, so Hobbs said it was now Mount Charles F. Brush — for the inventor of the Brush arc light, of course, a Michigan graduate of 1869. (That was no minor light; it replaced gas lights on the streets of many cities.)

Another peak became Mount Roy D. Chapin, named for the co-founder of Detroit’s Hudson Motor Company, who dropped out of U-M in 1901 to pursue his fortune in the fledging auto industry. Finally, Hobbs left behind Mount Willard M. Clapp. Clapp’s relationship to U-M, if any, seems to have escaped the historical record, but he was a well-to-do Clevelander, so possibly he was one of Hobbs’ benefactors.

Hobbs led two more expeditions to Greenland. One made international headlines — not for scientific discoveries, but for an airplane crash. Hobbs and his party rescued the two American fliers, who had been trying (partly at Hobbs’ urging) to prove the value of the “great circle” route from North America to Europe. [See “An Arctic Escape.”]

None of Hobbs’ U-M names stuck to the map of Greenland. But his own name was given by others to glaciers and a couple of land masses in both Greenland and Antarctica, plus a mountain range in the Arctic.

Hobbs died in Ann Arbor at age 88 on New Year’s Day, 1953.

Sources included William Herbert Hobbs, “The First Greenland Expedition of the University,” Michigan Alumnus, 10/23/1926 and An Explorer-Scientist’s Pilgrimage (1952); Madeleine Bradford, “An Arctic Escape,” Bentley Historical Library; Lawrence M. Gould, “Obituary: William Herbert Hobbs,” Geographical Review (July 1953); Donald H. Chapman, review, An Explorer-Scientist’s Pilgrimage, Journal of Geology (March 1954); and George D. Hubbard, “William Herbert Hobbs: 1864-1953, Science (5/15/1953). Lead image of Hobbs, third from right, with members of his team on one of the later Greenland expeditions, comes from U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Bob Eckardt - 77, 86

Brush was a Clevelander too, so Hobbs must have had some connection to Cleveland.

Reply

David Bloom - Faculty, Medical School

Superb piece. A shame that Hobb’s department disappeared at UM.

Reply

James Tobin - 1978,1986

The study of geology continues in the university’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

Reply

Perry Samson

The University of Michigan has a long-standing presence in Greenland through its Department of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering. Researchers have installed scientific instruments called magnetometers to study solar winds and their effects. Additionally, undergraduate students have conducted expeditions to measure weather and climate conditions, contributing to our understanding of climate change. During these expeditions, students also documented the historic Hobbs research site, leading to an Emmy-winning documentary (https://youtu.be/NJ-V2KL0boo).

Reply

Donnelly Hadden - 1961

If Trump takes over Greenland then maybe it should become a county of Michigan.

Reply

John Palmisano

The pilots rescued, Parker and Cramer, attempted and failed twice, to fly the great circle route. Their first attempt was flying the “Greater Rockford” and their second, the “Untin Bowler”. On both failed attempts, the pilots were located by Hobbs and his team aided by the telegraph operators Paul Oscanyan and Fred Albertson (UM Amateur Radio Club).

Reply

Mike Jefferson - 1978

“What is it about Greenland that tickles the acquisitive spirit?” Let me try to answer that for you. It’s large, remote, untamed, but relatively accessible to explorers. The UofM connection is pretty cool, though I am surprised that they would tolerate a book on dead white men imperialists. Definitely not woke!

Reply

Sandy Levin - 1975

can we stop with the silliness about woke and dead white men? And who is the they ?

Reply

Simon Stoddart - 1983

Are you making the case for Trump?

Reply

Deborah Holdship

No.

Reply

Mark Seidenberg - 1965, 1971, 1980 (different Universities)

This was a great article. I did not know that was done.

I do not think.it is to late to place U-M names on the maps for unmanned places at the time of his visits.

Now a little history. At eight bells on 13 September 1871, a landing party from the United States Navy ship the USS Polaris came ashore at Thank God Harbor, Greenland and took formal possession in the name of: “Jehovah (YHVH), POTUS, the SecNav, with three cheers and an American Tiger”. That was the form of taking possessions the United States Navy adopted in 1867 at the Brooks Islands. Now known as Midway Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. It was Captain William Reynolds, USN who came up with that Annexation Form the United States Navy used in to year 1925 by the landing at Swain’s Atoll in Pacific Ocean from.the

USS Ontario.

In Room.42, at the United States Capitol.on 17 December 1883, Senator Benjamin Harrison discussed

adding Greenland in future to Alaska with.Major Ezra W. Clark, Jr., USV (ret.), who served as both.the Chief of the.United States Revenue Marine and the lawyer for the Alaska Board of the United States Department of the Treasury. Harrison at the time was Chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Territories.

Section 1 of the Harrison Alaska Organic Act of 17 May 1884 has Alaska territory divided into to types, viz., acquired by the Treaty of Washington (a.k.a. Alaska Treaty) of 30 March 1867 and the alternative being declared land “Known.as Alaska”. Section 1 of the Act of 17 May 1884 has been.decussed in dicta twice by the.United States.Supreme Court, viz., In Re Cooper (1892) and Binns v. United States (1904) [one of the insular cases].

I am rooting Greenland will be added to Alaska, because that was the idea of Benjamin Harrison on 17 December 1883.

Reply

henrik dupont - 1977

The Vikings didn’t wanted Greenland — some Norsemen settled out from Iceland 985 seeking new land and escape from lawlessness. They were followed by other norsemen and created two settlements, Western and Eastern Village, with a maximum of 4000 people in Southwest Greenland –protected by the Norwegian king from 1260 and therefore part of the united Danish-Norwegian kingdom created around 1380. The Norsemen disappeared around 1450 but the area was claimed by the Danish king and Denmark started colonizing Western Greenland in 1721.

Reply

Mark Seidenberg - 1965, 1971, 1980, (different UNIVERSITIES)

Henrik Dupont at the class of 1977.

Why are you claiming disappearance “around 1450”, when a dead Norseman was located on the beach in the 1540s in sealskin suit by crew from a ship that went off course to Greenland

and a landing party discovered the body was killed by others wearing home made wool undergarments under the sealskin suit.

Could you have transported the number 54 to be come 45?

Reply

Chris Campbell - Rackham, 1972; Law, 1975

Were these expeditions on the schooner Effie M. Morrissey under Capt. Bob Bartlett? My book of Bartlett’s account of trips into the Arctic in those years is at my office and I can’t check right now.

Reply

Chris Campbell - Rackham, 1972; Law, 1975

Replying to myself: Yes, the Hobbs expedition seem to have been aboard Capt.Bartlett’s schooner. In the book Sails Over Ice (1934), Bartlett recounts a 1926 trip with Hobbs. Bartlett had been the captain for Stefansson’s failed 1913 Karluk expedition and had better luck in his own vessel built in 1894. That boat, Effie M. Morrissey,now known as Ernestina-Morrissey, still sails from Massachusetts.

Reply

Mark Seidenberg - 1965, 1971, 1980 (different Universities)

Chris Campbell (if I may),

I had the same questions about the schooner Effie M. Morrissey that you had when I read this article. Bob Bartlett

was listed in Hobbs correspondence file. When I looked at Bartlett’s papers at Bowdoin College in 1977, I must of missed that link. At the time I was looking for information about Bartlett walking from Blossom Point on Wrangell Island to Siberia in 1914. That was after the sinking of the Karluk in circa 1914. Bartlett was a Lt. Commander in the USNR. Blossom Point was name by Hunt after his future wife in 1881. Stef errored when he claimed it was named for the HMS Blossom. That is a good question for Dr. Susan Kaplan at Bowdoin College.

Reply