This is personal

They call it the Trail of Tears. It could just as easily be called the trail of deception, cruelty, and lies. Of broken promises that were never fulfilled. It’s also a trail of resilience, character, and strength in the face of tremendous obstacles. And for James Barnes, JD ’70, it’s a trail of his proud family history.

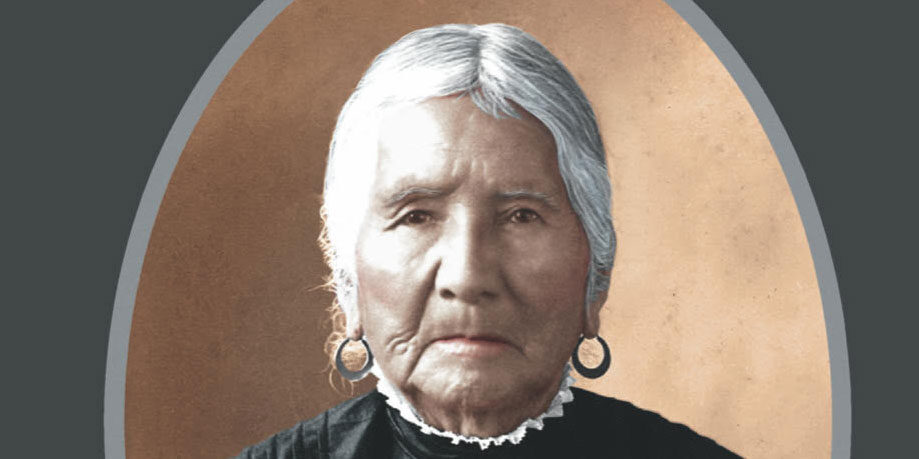

When Barnes, a retired environmental lawyer, began researching his Cherokee ancestry, he realized the life and death of his great-great-grandmother, Annie Spirit (1826-1910), served as two bookends coinciding with the tribe’s sovereignty and ultimate demise. He’d always been invested in his heritage, and the more he learned about Annie Spirit’s life and expansive family, the more a narrative emerged about this tragic tale in human history.

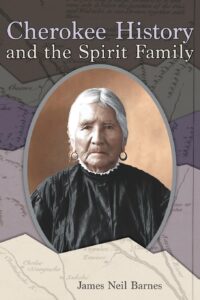

Barnes’ post-lawyer lifestyle in an ordinary French village allowed him to explore his lineage beyond the familiar tales he’d known as a child. It also gave him a chance to fulfill a long-deferred dream to write those stories down. It took about five years to complete “Cherokee History and the Spirit Family” (University of North Georgia Press) once he immersed in a trove of records sourced from his relatives.

“There’s been a lot of Cherokee histories written, but none of them from the point of view of a family,” says Barnes. “So, in a sense, this is a hybrid history. I cover the same history you’ll find in most books, although from my point of view. It’s personal in that sense, and in following my family’s lives in detail.”

Living history

Annie Spirit was born into a thriving Cherokee nation with full control over an enormous area of the Southeastern U.S. Her people were governed by their own constitution, legislature, and court system, including a Supreme Court. Most of the population was literate by the 1820s, thanks to free public education and a simple syllabary created by the polymath Sequoyah. He created 86 characters to represent the syllables from which all Cherokee words are formed. As a result, extensive records reveal virtually every aspect of Cherokee life from that time, including their unfortunate dealings with the American government. No other tribe is documented with such specificity, Barnes says.

“They had every reason to believe their civilization would flower,” he says. “And then Andrew Jackson was elected president in 1828. He basically hated Indians, and he wanted to get rid of all the Indians in the Southeast United States. He more or less achieved that goal with the Indian Removal Act of 1830. And what he didn’t achieve, the next president picked up and continued.

“I learned there were lots of trails of tears,” Barnes continues, “because many, many tribes faced the same fate.”

Accessible history

While the book is the story of his own family, Barnes sought to make his account accessible to any historian, teacher, or casual reader. The saga begins in an Eden-like haven, a matrilineal society in which females owned the property and inherited the wealth. But the idyllic scenario falls apart quickly. Soon, the reader is embroiled in a tragic loop of cruelty and deception in which communities are destroyed, rebuilt, destroyed, rebuilt, and destroyed again.

Most of the Cherokee population was literate by the 1820s, thanks to free public education and a simple syllabary created by the polymath Sequoyah. (Image courtesy of Barnes.)

Barnes follows the trajectory of Cherokee representatives who negotiated treaty after unenforced treaty. He writes about Cherokee lawyers winning court cases that were never enforced. He counts the millions of dollars that never materialized as the tribe was robbed of its precious land over and over again.

The soft cover book includes color photographs — paintings of chiefs, dignitaries, and relatives — as well as historical maps of the original territories and ceded lands.

“I think you learn a lot just from looking at paintings of these Cherokee chiefs of the 1700s,” he says, “like who were these chiefs who went to meet the king in 1735?”

Copies of diagrams, documents, and detailed records chronicle the once-thriving, independent Cherokee nation.

“They insisted that if they were going to be removed from their homeland, then somebody had to come in and appraise all their property,” Barnes says.

Thus, his book includes examples in which government officials visited virtually every Cherokee family in eastern Alabama, northern Georgia, Tennessee, and western North Carolina, among other states: Does this family own a house? How big is it? Does it have plank floors? Does it have a chimney? What kind of chimney? Does it contain pewter cutlery? At Barnes’ great-great-grandfather’s home, the assessor found a violin.

The Civil War

The Royce list of Cherokee land ceded to the United States between 1721-1866 totals some 81.2 million acres and 126,906 square miles. Click on the image to enlarge it. (Image courtesy of Barnes.)

With each move to new territory, the Cherokees continued to be a sovereign nation, and by the 1850s, they had some of the best schools in the country, including the equivalent of a junior college. Things were looking good. Then, the Civil War swept through the area. Barnes’ relatives fought on both sides, as the Union and Confederacy competed for their allyship, which was never rewarded. Barnes was disturbed to discover some Cherokees enslaved people, with the almost purely white Cherokees among the most abominable enslavers. He was devasted to learn his triple-great-grandfather, Buffalo Fish Spirit, had three enslaved people.

“No one in the family had ever talked about it,” he says. “That was a difficult chapter to write.”

However, assessments from 1835-36 indicate the family’s enslaved people lived in a two-story house with a chimney and plank flooring, similar to Buffalo Fish Spirit’s. They were among the most literate in the household. One was a weaver, another a blacksmith.

“They were treated OK, almost like family,” Barnes says. “And I learned the great majority of Cherokees who sided with the North freed all their slaves in the middle of the war. As far as I can tell, many stayed on the property because that’s where they lived. That assuaged my guilt.”

Once the war ended, the Cherokee nation began moving forward again, but in the 1880s, Congress decided that the Native Americans needed to be “civilized.” And though the tribe had won their sovereignty via the U.S. Supreme Court, it was relinquished yet again.

By 1908, Oklahoma was declared a state and the tribal nations were collapsed, the educational systems were seized, and their newspapers closed.

“So, near the end of my great-great grandmother’s life, she had to watch the taking away of everything she’d fought for,” Barnes says. “In spite of that, the people stayed together.”

A family’s American story

Barnes had long desired to record his family’s history, but was consumed with a career representing the unrepresented. In college, he advocated for anti-Vietnam War protesters who Ann Arbor landlords had blacklisted.

Professionally, he became an environmental lawyer working on behalf of the Indigenous people in Alaska and seeking to stop the building of the Alyeska Pipeline. The Center for Law and Social Policy won the case before the U.S. Supreme Court, but Richard Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, cast the tie-breaking vote in the Senate that allowed construction.

After working as a public interest lawyer in Washington, D.C., for nearly 10 years, Barnes focused his career on protecting Antarctica. He retired at 70, having decamped to France in 1994.

In writing the book, Barnes tapped into the research skills he perfected as a lawyer. His research began with his extended family, an extensive network of cousins and other relatives who held all manner of family documents, maps, and pictures, including the cover photo of his great-great-grandmother. The family Bible was in the hands of a second cousin in Wichita; it held valuable information about births, deaths, and marriages.

“Every one of my relatives has their own family history, and over time, all these pieces just flowed in,” he says. “Finally, I had the time to put it all together.”

The struggle continues

In the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon signed the Indian Reorganization Act, and almost all the tribes were given back some control over their reservation lands. The Cherokee reservation in northeastern Oklahoma is home to more than 150,000 people. They have been electing chiefs for the past five decades. One of Barnes’ goals is to get the U.S. government to enforce an 1835 treaty provision that promised the tribe they would have a non-voting representative in the U.S. Congress.

“To this day, Congress has never seated our Cherokee delegate,” says Barnes.

He’s working now with the chief and other people to ensure that the designated representative — Kimberly Teehee — is finally seated as a representative of the Cherokee nation.

(Lead image: Annie Spirit, courtesy of Barnes.)

David Schraver - 1970 (JD)

Congratulations to Jim on the book. Great review and interview. Would be good to let readers know how to get the book. Likely to be of interest to Law School Class of 1970 which will be gathering for reunion in the Fall.

Reply

Deborah Holdship

I bought my copy at Amazon. Also, the University of North Georgia Press provides links as to where you can purchase: https://ung.edu/university-press/books/cherokee-history-and-the-spirit-family.php

Reply

Jessica RICKERT - 1975

Kudos on a wonderful book!! We AIAN are proud of you.

In 1975, I graduated DDS, the first female AI dentist. UM was horrible to me.

There are 400 AI DDS in USA. So sad.

Reply

Veretta Coleman

Dear Mr. Barnes, I am glad you were able to write about your family’s history; it was very informative. However, I am saddened to read that because the slaves your family had were treated okay (almost like family), “That assuaged my guilt”. As an African American woman of multiple cultures, including Seminole, we’ve always been aware of Indians holding enslaved people. Never have I ever read that a person’s guilt over holding enslaved people was assuaged due to the enslaved being treated okay by their enslavers. Really?

Reply