Instant gratification

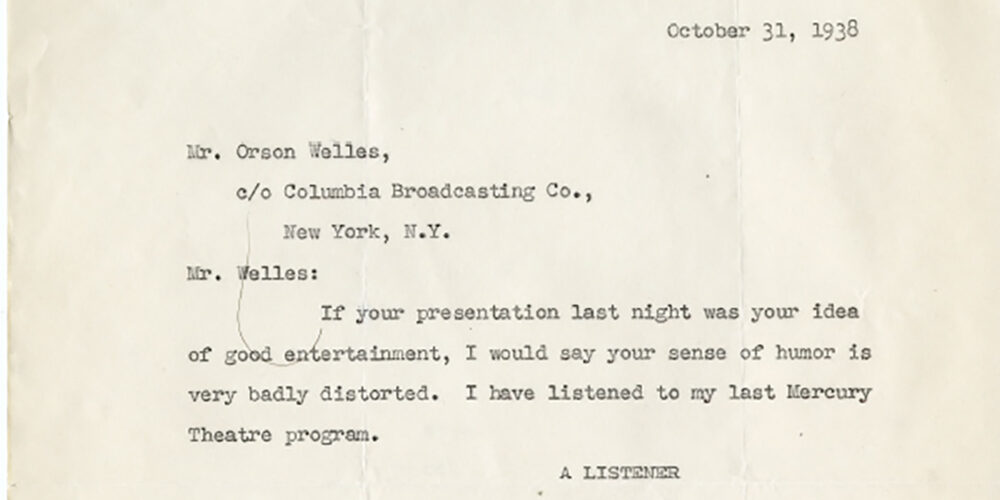

A volunteer team of citizen-researchers supported the U-M Library recently by digitizing, transcribing, and categorizing more than 1,300 fan letters sent in response to the 1938 radio broadcast of Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds.” The digitized archive recontextualizes one of the most unusual media events in history and reveals the “fake news” it generated.

Volunteers used the crowd-sourcing platform Zooniverse to complete the massive digitization in just one day. The entire collection of letters, part of the University’s Screen Arts Mavericks & Makers Collection, is now open to researchers and fans worldwide.As host of the CBS radio series “The Mercury Theatre on the Air,” Welles chose the night before Halloween to dramatize an extraterrestrial invasion based on the H.G. Wells novel. The radio play was an event unto itself, but the aftermath contains the real story. Headlines at the time described hysterical listeners flooding the streets in a panicked attempt to escape the encroaching aliens.

Rewrite

The digitized letters in the artist’s archive reframe that long-held narrative, revealing the power of primary sources.

“These letters capture a unique moment in history as experienced by people from throughout the United States and from many walks of life, and now anyone can read them, study them, teach with them, and use them to support research we can only begin to imagine,” says Phil Hallman, curator of the collection and one of the leads on the “War of the Worlds” project.

Vince Longo began working on the project as a U-M graduate student; he is now an assistant professor at Western Michigan University, where he seeks to create educational environments, platforms, and resources that help teachers and students utilize primary sources to deepen the meaning of research and coursework. It was “the greatest pleasure and honor” of his life to work with the Welles materials, Longo says.

Crowd work

The library production brought together technical, subject area, and crowdsourcing expertise to yield an invaluable resource with vast potential for discovery. However, even before the materials were widely accessible, researchers were drawn to the collection.

Alumnus A. Brad Schwartz used the archive as the basis of his 2012 honors thesis. Once he began reading the correspondence, Schwartz realized most listeners knew the radio play was pure entertainment. The experience of mass terror, seized upon by the media at the time, was minimal in comparison.

“There was a much more interesting, more nuanced story here that only this material could tell,” Schwartz says. “What I was on the verge of discovering was what would become the ‘fake news’ phenomenon. Rarely do you know in the moment that something is changing your life, but I had that sense in this moment.”

Schwartz’s thesis evolved into a 2013 episode of the PBS series “The American Experience.” He co-wrote the “War of the Worlds” episode and followed up with the 2015 book, “Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News.”

The author’s use of the term predated the announcement of Donald Trump’s candidacy for the 2016 presidential election, but it’s likely Trump’s obsession with the term led to some bonus traffic to the book’s website, Schwartz says.

In reality, most Americans missed the “War of the Worlds” radio broadcasts, but “everyone saw the headlines in the newspapers the next day,” Schwartz says. “The reason some portion of the audience believed this was because it played into their preexisting fears and biases. That is how misinformation and fake news work. But media literacy is teachable. You can’t prevent people from falling for everything, but you can give them the skills to protect themselves, and that is one way on an individual level we can get our up-and-coming generations thinking more critically.”

Revelations

For Schwartz, the “a-ha moment” in his research career occurred when Hallman paid his class a visit to discuss what materials were available to them through the Special Collections Research Center, including these boxes of fan mail.

“I vividly remember walking out of the Modern Languages Building thinking, ‘There’s a book in there somewhere …’ But I didn’t know what the book would be,” Schwartz says.

“I assumed, as I think everybody would knowing the story of how this broadcast supposedly caused a panic, that you would go through the letters and find stories of people fleeing their homes, grabbing their shotgun, collecting their money and belongings … and that is in there, but it is a much, much smaller part of the story than anyone realized.”

Once Schwartz decided to use the letters as the basis of his honors thesis, he dove into the Michigan section of the archive, organized by state. The first letter in the bunch was written on U-M Union letterhead, praising Welles and thanking him for his creative work. Several more letters of support — and criticism — followed. Some writers expressed concern about how realistic the broadcast sounded and how easily a populace could be manipulated.

“I had discovered that this moment in fall of 1938 is probably the first time in American history when you have the nation as a whole wrestling with this question of ‘Can democracy survive if this new electronic medium can make lies sound as convincing as truth?'”

Schwartz believes this has become the critical question of the 21st century, and the larger, more global fear that “War of the Worlds” created.

Across the Zooniverse

After the PBS series aired in 2013, Hallman says requests for access to the Welles materials increased, which spurred the idea to digitize the letters for public consumption.Digitizing these valuable resources has cut out several time-consuming barriers to access, making the collection available on-demand for use in classrooms and lesson plans.

“Welles was an innovator who pushed the boundaries of every media he worked in, both technically and in the stories he wanted to tell,” Hallman says. “So I think people will continue to find relevance in both the work itself, and in how people responded to it, for the foreseeable future.”

Thanks to the successful Zooniverse campaign, nearly every one of the 1,349 letters was transcribed and tagged overnight by 1,291 volunteers. Generally, a Zooniverse project can take weeks to years to complete, so the speedy nature of the project and the enthusiasm of its participants took the U-M team by surprise.

“I thought it would take a couple of weeks to complete and was planning with my colleague to take turns answering questions and monitoring responses that came through the site,” Longo says. “But when we checked Zooniverse the next day, everything was transcribed within 24 hours, and we even got complaints that there weren’t enough letters, or enough categories, to choose from. It just shows this is one of those energizing stories in the world.”