A fast start

In the farming town of Carrollton, Missouri, pop. 4,554, James Johnson Duderstadt grew to 6’5.” At Yale, he played football, majored in electrical engineering, and graduated summa cum laude. He earned his Ph.D. at CalTech in three years, then worked briefly on nuclear-powered rockets for Mars missions. He moved to Michigan, spent 12 years as a professor of nuclear engineering, and became dean of the College of Engineering at 38.

He was just getting started.

During his deanship (1981-86), COE’s share of the University’s budget tripled. He initiated $75 million in construction projects, all but completing the infrastructure of North Campus. He created one of the country’s most advanced computing centers. He hired 120 professors, 40 percent of the engineering faculty.

In 1986, President Harold T. Shapiro selected Duderstadt to become provost, the University’s chief academic officer. Two years later, he succeeded Shapiro as president.

‘Rethinking what the future will be’

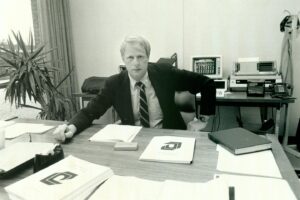

James J. Duderstadt was Michigan’s youngest dean of engineering. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Duderstadt said bricks and mortar were only the physical platform for pursuing his real goal — to make Michigan a leader in the transformation of higher education for the digital future.

“What I see there,” Douglas Van Houweling, whom Duderstadt hired as vice provost for information technology, said later, “is a creative, energetic, intelligent person constantly thinking and rethinking what the future will be. There are a lot of people in the world who assume that, outside of some very narrow parameters, they are controlled by their environment. Jim assumes the opposite. It’s sort of like, ‘The world is out there to be changed for the better,’ and that’s what his life is about.”

Duderstadt’s initiatives spanned the campus. But his vision of higher education’s future — or, more accurately, his ideas for how to bring that future about — came into focus in a single building that rose at the center of North Campus during his presidency.

A place for making things

The Duderstadt Center’s sharp geometric lines were designed by Detroit’s Albert Kahn Associates Inc. (Image: Joseph Xu, Michigan Engineering.)

It would stand in the midst of departments that make things — engineering, architecture, art, design, the performing arts, music. That suggested a community of interest. In the early 1990s, the Internet was new. Information was just beginning to go digital. But in each of North Campus’ academic areas, creators were embracing sophisticated new technologies.

So the North Campus deans and the building’s designers — led by the architect William L. Demiene of Detroit-based Albert Kahn Associates — filled its 250,000 square feet with spaces for students, faculty, staff, and professional practitioners to use the latest tools of their trades together. Here they would be urged to cross disciplinary boundaries and collaborate on digital works of art; audio and video productions; 3-D fabrication; and virtual-reality presentations.

Built with $40 million from the state of Michigan, it was dedicated in June 1996 as the Media Union, Duderstadt’s play on words to echo “Michigan Union.” At the dedication ceremony, he said: “It is destined to help create a new kind of university that breaks the constraints of academic disciplines, along with constraints of space and time.”

From the first, it was open around the clock. Students swarmed in. As imagined, it became the center of everyday life on North Campus and a hive of intellectual tinkering, making, experimentation, even play, with students taking up every micro-generation of new technology.

In 2003, the Media Union was renamed the James and Anne Duderstadt Center.

Universities of the future

When Duderstadt left the presidency in 1996, he moved into new quarters in Room 2001 of the Media Union. The sign on the door said: “The Millennium Project.” He turned his full attention to projects aimed at inventing the universities of the future, with students who already were approaching education as “a plug-and-play experience, unaccustomed and unwilling to learn sequentially, to read the manual, and inclined to plunge in and learn by participation and experimentation.” He wrote a series of books about higher education and the University.Technology continued to fascinate him. But to grasp its full potential, he said, universities would need to reimagine their mission. Given the nature and pace of change, the nation should embrace a “culture of learning” with the enthusiasm of the Space Race in the 1960s. The line between student and graduate might well disappear. One might belong to the University of Michigan for a lifetime, he said, first learning how to earn a living, then returning again and again to explore new questions in mid-life and beyond.

“The way to think of the technology is as a way to free human interaction from the constraints of time and space,” he said in 1998, echoing his vision for the Media Union. “The technology itself is simply a tool to better enable natural human interaction.”

Duderstadt died in Ann Arbor on Aug. 21, 2024, at the age of 81.

Sources included James J. Duderstadt, On the Move: A Personal History of Michigan’s College of Engineering in Modern Times (2003); and James Tobin, “The Futurist,” Ann Arbor Observer, September 1998. Lead image of ‘The Dude’: Michigan Photography.

Don Kenney - MSE 1972, PhD Aero 1976

I knew Jim very well during his period as Professor of Nuclear Engineering. He was on my PhD thesis committee and a member of the Parish Council at St Mary’s Student Chapel. It was after my time, but his leadership during his Presidency concerning the issue of U of M’s admission policies should not be overlooked. The lawsuit over the policies was decided in the Supreme Court.

Reply

Peter Eckstein - 1958

When I was working on economic development for the State of Michigan, I had many chances to interact with Jim and his outstanding assistant deans, Chuck Vest and Dan Atkins. He gave me a chance to very briefly interview Steve Jobs. More important, he took the time to show me how a Macintosh could enable a user to write a word or a paragraph and then instantly convert it into any one of a wide range of sizes and typefaces. This is totally pedestrian stuff today, but I was wowed and went out and bought my first Macintosh–with fully 128K of memory!–for a wholesale price of “only” $2,500. It was a start, anyway, and I will always remember Jim fondly for that.

Reply

David Erdody - 1988 EMU

I worked directly with him through the Bentley Historical Library. One day when he and I were sitting there and I didn’t realize I might have gone and pulled the UM’s infamous PORT HURON STATEMENT (Not the compromised second draft..) and photoed him with it. Instead, on an other occasion, I came across much more meaningful (original) photos under Ann Duderstadt’s project dated, as it later turned out, from November 5th 1962. See: Michigan Union lobby.

In a grand, lasting way, he was the right UM President at the right time in history–the internet itself went viral throughout campus on his watch.

Reply

David Erdody - 1988 EMU

p.s. “The most important thing a university president can do,

besides bring in money, is to pick good Deans.”

–JJD to DE

Reply

Cletus Bost - 1971, 1978

Jim Duderstadt’s vision for the future of the university and for nuclear engineering as promise for the future was cast in every one of his lectures and his books. I would advocate for a University lectureship dedicated to Jim’s vision. He was my Professor, my friend and my colleague for over 50 years.

Reply