Spitting image

Students in the early 1900s. No spitting here. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Students casually spitting on classroom floors — that was apparently the last straw for Dr. Aldred Scott Warthin.

In 1910, Warthin served not only as U-M’s chief professor of pathology but as chair of Ann Arbor’s chapter of the Michigan Anti-Tuberculosis Society, and he was the loudest voice in town in favor of cleaning up the campus — because in the early 20th century, the campus, truth be told, was a dirty, smelly, and downright unsanitary place.

Unpaved streets and alleys were slog-pits of mud in the slushy Michigan winter, then wind tunnels of malodorous dust under the summer sun. On a rainy day, you never knew for sure what was running through the gutters.

Until recently, most students, faculty, and staff had answered the call of nature in big his-and-hers outhouses tagged with such unloving nicknames as “Campus Beauty.” In 1871, James Burrill Angell told the regents he wouldn’t accept the presidency unless a flush toilet were installed in the president’s house. It was the first in town, and it was decades before toilets and sewer systems became the rule instead of the exception.

In 1912, leaky manure bins still sat behind many a building around town. There was even one in the alley behind the fire station on East University, next-door to Tappan School.

Tumors and toes

President Angell did his best to keep the U-M community healthy with warnings like these. See larger version. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

A few blocks to the north, at the rambling labyrinth of buildings that constituted the old University Hospital, conditions were not much better. The hospital had a national reputation because of its first-rate teaching faculty. But the facilities themselves, overburdened by patients from all over the state, had deteriorated into “a most shocking condition,” according to Dr. Reuben Peterson, the medical director.

“Piles of dirt are allowed to accumulate in corridors, wards, and private rooms,” Peterson lamented — even as orderlies trudged through the corridors with leaky baskets bearing excised tumors, tonsils, and toes.

Proper ventilation was scarce. From University Hall on the west side of the Diag to the Medical School on the east, buildings were either hot and stuffy or dismally drafty. Science students sitting in lecture halls were only too aware when animals were being dissected in the labs down the hall.

And Ann Arbor’s water system, still in private hands nearly a century after the town’s founding, was the focus of chronic suspicions, especially since an outbreak of typhoid fever had been traced to tainted city water. As a result, students eased into the University’s three swimming pools with no small bit of trepidation.

Needless to say, when Dr. Warthin raised the flag for deep-cleaning the campus, he had plenty of allies.

A clean campaign

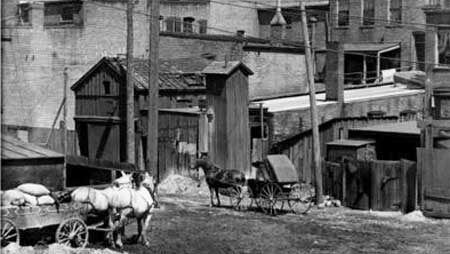

This unpaved Ann Arbor alley in 1911 probably included manure bins, a common suspect in the war on germs. (Image: Sam Sturgis Collection, U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Warthin, a dapper man who mixed a devotion to medicine with a deep love of gardening, was a pioneer in studying the genetics of cancer. But lately he had joined the Progressive Era’s broad-ranging campaign to ameliorate the ills of an urbanizing and industrializing society.

The scourge of tuberculosis was his bete noire, largely because it was so preventable, if only people would keep their bodily fluids to themselves. Yet of U-M’s roughly 5,500 students, Warthin estimated 500 eventually would die of TB, and many of those would contract the germ as young adults in Ann Arbor — no doubt in part because human sputum was allowed to fly with impunity.

Warthin asked: “What use is the attempt to fix an expensive education upon a young man or woman if the educated one is to die of tuberculosis or typhoid fever or one of the other preventable diseases?”

Spitting in public violated an Ann Arbor ordinance, he fumed, but “has one single attempt ever been made by the police of Ann Arbor to enforce this ordinance? When the streets are impassable we may be arrested if we ride wheels [bicycles] upon the sidewalks but the spread of disease-germs goes on without interference.”

The sight of students spitting on sidewalks, stairways, and even the floors of classrooms drove him nearly nuts. Common drinking cups were supposed to be banned, but Warthin saw them all over town.

So Warthin spearheaded a Committee on University Sanitation that studied the situation, then sent proposals to the faculty senate and the regents. Within a couple of years, new rules and practices were in place.

Coming clean

This outhouse was nicknamed “Campus Beauty.” (Image: Sam Sturgis Collection, U-M’s Bentley HIstorical Library.)

Manure bins were removed. Students who spat in public were to be suspended. Any student with a chronic cough would be asked to submit a sputum sample to the hygiene lab. A push from the Michigan Union — a powerful organization representing student interests — spurred plans for an infirmary devoted solely to treating students. Samples of the water and air supplies were to be taken regularly. Five thousand fly swatters were passed out to Ann Arbor kids, with bounties paid for carcasses. And as new buildings were planned, far more attention would be paid to proper ventilation and sanitation.

The crowning achievement of the campaign was the University Health Service. Before turning chiefly to the medical care of students, UHS concentrated for several years on securing the improvements in sanitation that Warthin’s committee had won. It opened its doors in a converted residence on Tappan Street, where the Burton Memorial Tower stands now, in the fall of 1913.

Sources include Aldred Warthin, “The Physical Health of the University” [undated brochure] in Warthin’s papers, Bentley Historical Library; the papers of the Faculty Senate, Bentley Historical Library; J. Fraser Cocks, Pictorial History of Ann Arbor, 1824-1974; the Ann Arbor Times-News; The University of Michigan: An Encyclopedic Survey; Michigan Alumnus; and James Tobin, “The Pavilion Hospital,” “The Catherine Street Hospital(s),” and “The Rise of ‘Old Main,’” Medicine at Michigan.

michael salwitz - 1970 SPH

As a physician in this age of “wonder drugs” and “marvelous cures” it is important to never forget that changes in public health conditions such as enclosing sewage ditches, treating raw sewage and drinking water being made safe for routine consumption have done more for the “public well being than all the truly wonderful advances in medicine that the last 100 years have witnessed.

Reply

George Davidson - 1954

I had just arrived from a four-year hitch in the regular navy to East Quad. The room for three was as big as the compartment aboard ship that held 12 sailors! What luxury. Then two sophomores left and I was alone for awhile until a new roommate appeared. He went off to get a physical and never returned. The X-ray had shown tuberculosis. I got many full-sized X-rays but I never got TB! Thank you University Health Services for checking for TB.

Reply

dave aussicker, Ph.D. - 1985

We have come a long way but interesting that a major source of infections remain in hospitals

Reply

Misty Berry - 1985

Could you imagine suspending someone NOW for spitting in public–even if it is a public health issue? UM won’t even suspend 4 students caught smoking pot in South quad and vandalizing their RA’s door in retaliation for reporting it. No, “it’s all about me” now. There needs to be a massive re-education on campus as to the problems with sexual promiscuity. Not only do we have problems with unplanned pregnancy but antibiotic resistance (GC/Chlamydia) and antivirals (HIV). Seems the attitude at the U is “the more the merrier” and God forbid we should make someone feel “bad” about their behavior. Very interesting article. I wish all students and faculty would read.

Reply