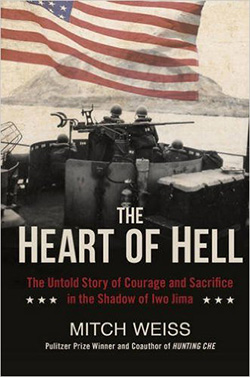

The untold story of courage and sacrifice

Willard Vincent Nash didn’t set out to be a hero — nor did the U.S. Navy sailors who served under him in the Pacific theater during World War II.

A native of Saginaw, Mich., Nash, BA’35/LLB ’35, left a successful legal practice to enlist in the Navy in 1942. He rose to the rank of lieutenant and became captain of the LCI-449, a Navy gunboat.

“A hands-on skipper, Nash made sure he knew the name of everyone on board,” writes Mitch Weiss in his new book The Heart of Hell, (Berkley Caliber, 2016), which recounts the lives of the sailors aboard the 449 as they prepared for the battle that would change their lives. “[To Nash] it was important that every crew member know his role on the gunboat and what was expected of him. That is why Nash talked personally to every sailor who joined the crew.”

The Heart of Hell provides plenty of heroes, including Nash, but there is also tragedy and death in the buildup to the U.S. invasion of Iwo Jima in February-March 1945. Two-thirds of the crew of the LCI-449 either died or were wounded in what Weiss calls the “battle before the battle,” a reconnaissance mission on Feb. 17, 1945, to scout possible landing sites on what was called “Island X”

By the time the crew of the LCI-449 was ready for combat, Nash had been promoted to commander of Group Eight, with a number of LCIs under his command. But his imprint on his original ship never left.

“Nash is the guy who ties it all together,” Weiss says. “He is an A-list character in the book. He won the Navy Cross, one of the service’s highest honors for his leadership in the battle before the battle.”

Ordinary guys who did extraordinary things

Dennis Blocker (above) shared his story with investigative reporter/novelist Weiss. (Image courtesy of Dennis Blocker.)

The Heart of Hell is Weiss’ fifth book but his first solo effort. The native New Yorker was a co-winner of the 2004 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting while working at The Toledo Blade. He currently writes for the Associated Press.

He was drawn to the story of the LCI-449 and its crew thanks to the efforts of Dennis Blocker, whose grandfather served on the ill-fated ship. Seaman First Class Clifford Lemke survived the horrific battle but returned home a different man. Although he and his wife raised six children and Lemke had a successful carpentry business outside Milwaukee, his family regarded him as a “functioning alcoholic.”

“Lemke’s wife died of cancer and Lemke was so depressed he committed suicide,” Weiss says. “Blocker’s family asked him ‘Could you find out what your grandfather did during the war that made him a changed person?’

“Blocker tried to find out. For 10 years he did research on his days off. He interviewed more than 100 people and put together a 100-page manuscript. He wanted someone to put the story together. He had just finished reading Hunting Che [co-authored by Weiss and Kevin Mauer]. And he called Kevin who passed along the story to me.”

Weiss says there was “something about one or two of the characters” that intrigued him. If he planned to write a book on the subject he needed to know much more about what made these guys tick.

“It’s all about telling the story,” Weiss says. “The more research I did, the more I found this was a group of ordinary guys who did extraordinary things” and who came to understand that combat is “90 percent boredom and 10 percent sheer terror.”

Life aboard the LCI-449

Weiss found scores of letters, describing in minute detail life aboard the LCI-449, what the men did and talked about during the hours of waiting for the next command. He was able to interview families of both survivors and casualties.

Weiss found scores of letters, describing in minute detail life aboard the LCI-449, what the men did and talked about during the hours of waiting for the next command. He was able to interview families of both survivors and casualties.

Blocker had concentrated solely on the day of the battle, Feb. 17, 1945. But Weiss wanted to set up the entire story, the sailors’ backgrounds, and their early days aboard the 449. Much of the pre-invasion narrative concerns the crew’s relationship with their commander, Michigan graduate Willard Nash.

“I contacted Nash’s son [Nash died in 1986 at 76],” Weiss says. “His father had never talked about the war. Nash was a by-the-book officer and was best friends with Rufus Herring — who replaced Nash as captain of the 449. They bonded over sailing. Nash takes him under his wing, and when Nash is promoted, Herring gets to be his successor. Nash led by example.”

Despite serious wounds, Herring survived the battle and lived until the age of 74 in 1996, but many of the men trained by Nash and Herring were not so fortunate. The Japanese weapons installations on Iwo Jima were far more extensive than what U.S. commanders had expected, and the small LCI crafts, particularly the 449, took a terrible pounding.

Newly married wives were turned into widows and some girlfriends never saw their men again. The horror from the Japanese bombardment was not a subject the surviving sailors were anxious to discuss.

“In talking to the daughter of Junior Hollowell, she said her father never talked about the war,” Weiss says. “He drank a lot. Lemke, who never drank before the war, became an alcoholic. They were suffering from post-traumatic stress, but that wasn’t diagnosed until decades later. The guys became withdrawn. When these men came back from the war who were they going to talk to? Their buddies were all over the country. They tried to bury the war.”

“I got to know these guys.”

Nash’s life turned out better than many under his command.

He married Dorothy Wallace, another Michigan graduate and a former press agent who had hung out with the likes of Frank Sinatra and Betty Grable. Nash and his new wife returned to Saginaw where he served as city attorney from 1946-78. He retained his love of sailing, joining the Saginaw Bay Yacht Club and sailing the Great Lakes prior to his death in 1976.

It is Nash’s leadership skills and sense of command that provide ballast for Weiss’ account of a star-crossed crew.

“Heart of Hell is really special because it’s an unknown story,” Weiss says. “I had withdrawal after I finished it because I got to know these guys. All of a sudden, I didn’t know them anymore. They’re a memory.”

Richard Wright - 1975

Before the landing at Iwo Jima, a group of Landing Craft Infantry ships (LCI’s) along with the LCI 449 were sent to bring Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT’s) to clear pathways to the beach for landing troops. The Japanese artillery hidden in the hillsides decimated the LCI fleet. Veteran LCI sailors still speculate whether the LCI’s were sacrificed to determine the locations of the gun emplacements on the island.

Reply

Peter D. Winer - 1961

The review makes this a must read for WWII/ military history buffs…. shows how WWII – like most wars – was fought by small groups of men in highly focused battles that were all melded into a much larger whole. No background music,no contrived plot, no special camera angles….. To the men in the small units, it just happens, when it happens…..and for the survivors, we must realize that the scars remain for each us to deal with as best we can… we must seek help if necessary and attack the challenges we face to continue living a productive life….

US Marine (Retired) VN era NROTC grad.

Reply