Where there’s smoke …

Competition did not just happen between classes, but also between schools, like the Laws and Lits in 1899. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.) See larger image.

It began one day in the latter part of April 1874, when three Michigan sophomores subjected three freshmen to the ritual of being “smoked out” — to have cigar smoke blown in your face until you retch or faint.

This was one of the era’s two most popular forms of “hazing,” the other being to hold a freshman’s face under a gushing water pump for an indefinite period — an ancestor of the modern method of coercive punishment called waterboarding.

There was nothing unusual in the hazing itself. What made it distinctive was the response from the faculty of the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts when they heard about it.

They suspended all six of the students.

Then things got interesting.

Injured honor

The hazing of freshmen by sophomores — a rite of passage borrowed from customs at least as old as the Middle Ages — was rampant at many American colleges.

The problem, of course, was that “the hazing of one year is the mother of the hazing of the next,” as Scribner’s Monthlyput it. “Every freshman who is hazed can heal his injured honor only by hazing. So custom perpetuates the evil through successive classes.”

Two years earlier, the Harvard faculty had asked entering freshmen and sophomores to sign a no-hazing pledge. Three hundred signed, and hazing ceased both that fall and the following. Yale’s faculty tried another tack — any sophomore caught hazing was demoted to rejoin the abhorred freshmen.

At Michigan, rowdyism had a long tradition. Ground combat called “rushes,” where crowds of “Lits” or “Meds” or “Laws” literally tried to push rivals off the campus, were annual events. (See “The Great Rush.”) Skirmishes between sophs and freshmen made corridors hazardous. Rotten vegetables and rocks flew overhead at morning chapel.

Some of it was dangerous, none of it was educational, and the tax-paying public was starting to think the University of Michigan was hosting a playpen for brawling brats.

Finally, the faculty had had it, and decided to make an example — thus the six suspensions, perpetrators and victims alike.

“We also have engaged in hazing”

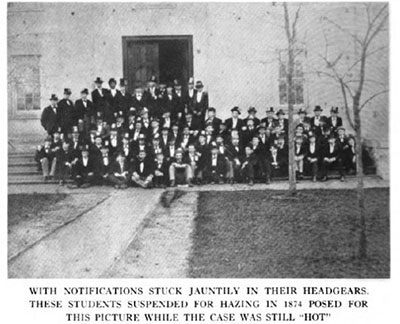

These brazen hooligans posed for photos while their case was still “hot.” See larger image.

The students proceeded to call the professors’ bluff.

At hastily called protest meetings, two petitions were passed around, one for sophomores, one for freshmen.

The petitions stated that the six suspended students had not been ringleaders, just innocent followers of a hallowed ritual; that hazing had been going on for ages with no warning that it might trigger suspensions; that the hazing had occurred off campus, and thus was not subject to U-M discipline; and finally — this was the zinger — “we also have been engaged in hazing,” and it was unjust to suspend only the six who were caught.

The signatures ran far down the page — 103 in all, a full 10 percent of the student body — so many, the signers apparently believed, that the faculty would never dare suspend them all.

There they miscalculated.

President James B. Angell warned that signers would face the same fate as the original six, but the decision was up to the LSA faculty, which was not to meet for several days.

In the interim, a rumor went around that anyone who crossed his name off the petition would be spared execution.

Twenty-two names disappeared. That still left 81.

The axe fell.

“Petty barbarism”

The 81 offenders were ordered off campus for the rest of the school year. If they passed exams in their unfinished courses, they could re-enter the following fall. (For reasons lost to history, any student enrolled in botany was exempted from the exam.)

Clearly, the professors were conscious of censorious eyes around the state.

“The public voice . . . demands that the University faculties . . . shall eradicate from the University the practice of hazing, and every other form of disorder which may bring upon it harm and disgrace,” the faculty’s report declared. “The University can better afford to be without students than without government, order, and reputation.”

News of the mass suspension made headlines across the state and far beyond.

A letter from an outraged junior — unsigned — was published in several places. The suspension of the six had been “an act of tyranny,” the protester insisted. Hazing was “mutual and good-humored” and never harmful. The faculty’s action was destructive of “that freedom of student life which has been, and is, one of the greatest attractions of the institution.”

This prompted catcalls wherever the letter was published. Press reaction was uniformly on the side of the professors, from The Boston Globe(“petty barbarism”) to The Chicago Tribune(“outrageous . . . a custom devoid of wit or fun”) to newspapers across Michigan.

The Detroit Post’scondemnation was typical. Hazing’s “whole tendency is degrading,” the paper said. It was no more than “coarse fun which the least thoughtlessness or ill temper transforms into dangerous violence.”

Aftermath

Here, sophomores “captured” freshmen from the class of 1911 in some bizarre ritual. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.) See larger image.

The Great Suspension, as it became known, had its intended effect — at least for a while.

Hazing at U-M was regarded as officially banned. According to a student journalist who reflected on the aftermath two years later, “a year or more of stupor and inactivity” had followed. But “the pent-up steam of a thousand students must find vent somewhere,” the writer observed, and at Michigan, the lid clamped on hazing had caused a surge of more wholesome student activities — newspapers, a rowing club, and other sports.

“Although the class of ’77 may never be able to recall some features of the Great Suspension without bitterness,” the editorialist wrote, “we think they will generally unite in saying that the effect of the abolition of hazing has been excellent not only upon the University at large, but particularly upon the classes now in college.”

But hazing was back in fashion soon enough, faculty or no faculty, though in time it was confined mostly to an annual day of hijinks called Black Friday.

Postscript: Many years later, someone traced the names of the 81 suspended sophomores and freshmen to see what had become of them.

The list included a justice of the Michigan Supreme Court, an attorney-general of Michigan, a University of Michigan regent, a professor of chemistry, a professor of mathematics, the president of the First National Bank of Monroe, and the superintendent of Ann Arbor’s public schools.

Sources included the papers of James Burrill Angell at the Bentley Historical Library; the Chronicle, predecessor of the Michigan Daily; “Faculty Discipline in the Seventies,” Michigan Alumnus, 7/11/1941; “Hazing, a la ’72, Was Indeed Strenuous,” Michigan Alumnus, 11/15/1930; “College Hazing,” Scribner’s Monthly, January 1879.

(Top image: A rowdy “flag rush” competition between freshmen and sophomores, 1916. Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)