The darkest hour

As the spring of 1792 approached, the French Revolution was turning dark. Three years earlier, revolutionaries had declared a new dawn of universal human rights. Now militants were mounting a reign of terror against aristocrats and menacing the Catholic Church, demanding that priests declare their allegiance to the secular French Republic.

At the Church’s Society of Saint Sulpice, an intellectual order devoted to education, a novice priest named Gabriel Richard, just 24, had quietly refused to swear the republican oath. His liberty was at risk, possibly his life. Priests cooperating with the Republic were informing on brothers who defied the Revolution.

In the last week of March, Father Richard heard of a ship named Reine des Coeurs — Queen of Hearts — that was about to sail from the Atlantic port of Le Havre for the United States. The captain sent word that he had room to smuggle a few priests out of the country. Reine Des Coeurs sailed on April 2 with Gabriel Richard aboard.

Four months later, anti-Church mobs in Paris murdered more than 200 defiant priests.

“A talent for 10 different things”

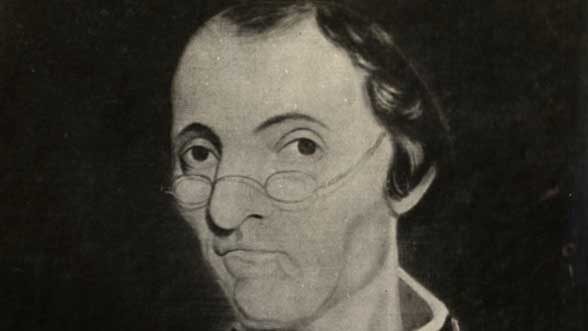

The young Father Richard was tall, stringy and homely, with long arms and big, bony hands. A scar down one cheek was a reminder of the day when, as a little boy, he had taken a terrifying fall from a high church scaffold. His jaw still twisted so dramatically when he chewed that his seminary friends called him “Father Wrymouth.” He was well-liked and much respected for his broad learning and his extraordinary energy. His bishop in the U.S. would soon say “he has a talent for doing 10 different things almost at the same time.”

First he taught math at the Sulpician seminary in Baltimore. Then he was sent west to work among Indians and frontiersmen along the Mississippi River. In 1798 he was transferred to Detroit, a trading post in the Northwest Territory with a fast-growing population of several hundred, a mix of Catholics and Protestants, many of them of French ancestry.

He was soon the pastor of Ste. Anne’s Church, the tallest structure in town, and engaged in the work of his life — to build a human infrastructure of good works and learning in his adopted community.

“Le Bon Pere”

Richard seemed to be everywhere at once.

He brought in looms and taught parishioners how to weave; acquired books for the church library; ran one school for girls and another for boys; visited the sick on distant farms; wrote and delivered his Sunday sermons; and argued religion and politics with friends of every party and sect.

With the only printing press in town, he founded and published Michigan’s first newspaper.He would teach one youngster to read while instructing another in math.

A continuing passion was to persuade the government in Washington to do right by the Native Americans whose lands the Americans now inhabited, “as it is well known by everyone,” he said, “that they have been grossly cheated.”

Within a few years most Detroiters regarded Richard as their unelected leader — Le Bon Pere, “the good father,” to everyone he met on the street, including Protestants, who soon asked if they could hold their services in Ste. Anne’s. He readily agreed. He once told an elderly Protestant lady: “If all Catholics were as good as you, there would be no trouble in the world.”

From the ashes

On the morning of June 11, 1805, an ember from a baker’s pipe dropped into a pile of hay in a barn, and within moments, flames were leaping across alleys and down the streets. Detroiters threw their goods into canoes and boats and rowed over the river toward the Canadian shore, then turned to watch their town burn. Within three hours, the only structures standing were stone chimneys. Ste. Anne’s was a smoking ruin, and all the food in town was gone.

When the devastated townspeople returned to Detroit, Father Richard was moving among them, organizing men into expeditions to go up and down the river, asking farmers on both sides for emergency loans of food.

He was soon among the leaders who began to plan and rebuild a new city laid out along great thoroughfares, including Jefferson Avenue (named for the president) and Michigan Avenue, the road to Chicago for which Father Richard himself would help to secure funding from Washington.

He coined a motto for the new Detroit: Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus —“We hope for better things; it shall arise from the ashes.”

Educator and legislator

U-M’s “Old University Building” in Detroit. (Image: Bentley Historical Library. See larger version.)

In the War of 1812, Detroit was at the center of fighting among the Americans, British, and Native American nations hoping that a British victory might slow American expansion to the west.

When British soldiers captured Detroit, Father Richard faced a new demand for his allegiance. He replied: “I have taken an oath to support the Constitution of the United States and I cannot take another. Do with me as you please.”

They locked him up, but only until the Shawnee chief Tecumseh said he would not rally his nation to the British side until Father Richard was released.

In 1815, the Americans won the war and resumed their march westward. As Detroit emerged from the tumult, Father Richard helped to negotiate the Treaty of Fort Meigs, by which Native American nations of the lower Great Lakes and Ohio River valley ceded their remaining lands to the U.S.

By one of the treaty’s provisions, many acres of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi land were set aside to support a new institution of education at Detroit. Funds from the sales of that land to settlers were the first endowment of a new University of Michigania, established in Detroit in 1817 and reconstituted in Ann Arbor in 1837.

With the territorial legislator Augustus Woodward, the Presbyterian minister John Monteith, and William Woodbridge, acting governor of the Michigan Territory, Father Richard designed a program of public education for the whole territory with the new university at its apex. In its Detroit era, this venture never became more than a little preparatory school. But it was the original incarnation of the University of Michigan, with Father Richard as vice president, professor, and trustee — at an annual salary of $18.75.

In 1823, his fellow citizens of the Michigan Territory chose him to be their nonvoting delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. Father Richard was the first Catholic priest to serve as a member of Congress.

A visitor from France

U-M’s Detroit Center opened in 2005. (Image: Michigan Photography.)

In the summer of 1831, the French traveler Alexis de Tocqueville, soon to be renowned for his seminal description of the United States, Democracy in America, sailed up the straits of Detroit from Lake Erie. Tocqueville and his traveling companion, Gustave de Beaumont, had been told of Michigan’s famous French monsignor. So upon disembarking at Detroit, “a fine American village,” they asked to be directed to Father Richard.

They found him teaching a dozen children in his classroom. They talked long into the evening. They had trouble getting the priest, “a fine old man,” to answer their specific questions, but they were “very much pleased” with the rambling conversation, filled with tales from Richard’s remarkable life, a recounting of Detroit’s history, and commentary on his American countrymen.

He shook his head at the multiplicity of Protestant denominations in the New World. Religious practice in America, he said, was a matter of toleration to the point of indifference. “You are not asked to what religion you belong,” he said, “but whether you can do the job.”

A year later, a cholera epidemic reached Detroit. Father Richard threw himself into the job of nursing the victims. Four days later he was dead.

In 1976, his remains were re-interred in the chapel at Ste. Anne’s, rebuilt in the 1880s as a soaring structure of brick and stone, near the altar where Le Bon Pere had celebrated mass for more than 30 years.

Sources included Dolorita Mast, Always the Priest: The Life of Father Gabriel Richard, S.S. (1965); Stanley Pargellis, Father Gabriel Richard (1950); Robert Conot, American Odyssey (1975); George Wilson Pierson, Tocqueville and Beaumont in America (1938). (Top image: Detroit Public Library.)

Patrick Reynolds - BM '81, MM '83

Great article, thanks! My first teaching position (35 years ago) was at Gabriel Richard High School in Ann Arbor.

Reply

Cynthia Coviak' - 1998 (PhD)

Thank you for this wonderful piece.

I am a descendent of the original French Catholic families of Detroit and grew up on the northeast side, just south of 8 Mile Rd. A school in the area was named after Richard. Although I learned a bit about many of the main figures in Detroit’s history over the years such as Cadillac and Lafayette, and about St. Anne’s Church, I didn’t know about Richard’s role in its development. Nor did I know the reasons for his presence in the region and the major roles he played in relationships with the Native American nations of the area.

Reply

George Gish - 1967

How wonderful to know this inspiring story of the founding father of the University of Michigan. It makes me even more proud to be an alumnus.

Reply

Mark Harshberger - 1988

Excellent article. I found it very informative.

Reply

Douglas Holmes - MS '60

Enjoyed the article on early U. of M. history and encourage Michigan Today to publish more.

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Hi, Douglas: If you are a fan of U-M history, I suggest you check out http://heritage.umich.edu. You’ll find a vast selection of beautifully written and informative features.

Reply

Mary Ann Cheng - '84 BS LS&A, '88 MD

Thank you for a wonderfully written article on a UM founding father. It’s refreshing that his Catholic connection was not downplayed. I’m proud to be a UM alum!

Reply

Gertrude Reen - Graduate School of public/Nutrition & Maternal Health 1967

A very interesting part of the University’s history. I had an inkling that there was a Catholic contribution but no one I met knew the specifics. This adds to my esteem of the University.

Trudy

Reply

Dennis Glasgow - '74 BA LS&A

Thanks for this fine article, evoking much sentiment. During my years at UM I attended Saint Mary Student Parish and its Newman center called “The Gabriel Richard Center” after the UM co-founder. With joy i returned to my old parish and Alma Mater as a Jesuit priest and associate pastor from 2000 to 2013. During novitiate in Detroit (’76-’79) I had made a day pilgrimage to Ste. Anne’s to venerate the remains of Father Gabriel Richard. I recommend it. At Holy Redeemer (Detroit) High School it was also a gift to take the Gabriel Richard Leadership Training Course. Father Richard has had a big impact on me. Merci, Bon Pere, merci.

Reply

Gary Bartz - 1964 Engineering

Very interesting article! As a youth, I went to Gabriel Richard elementary school (thru 8th grade) before entering the U of M in 1960!

Reply

James Davis - 1971 Ph. D.

Robust thanks for this highly interesting, informative, and inspiring article and for the sources cited after it. I greatly appreciate the opportunity to learn more about the life of this remarkable founder. It’s appropriate that the Newman Center in the Saint Mary Student Parish is named after him, but does anyone know if the university has ever honored him by naming a building after him or commissioning a statue? Also, as part of the Bicentennial activities, will there be panel discussion of his life and his diverse contributions to the development of the region? Again, thank you!

Reply

Judy Edward

Back in 1980 there was a Gabriel Richard public speaking course, a multi-week seminar that I took part in. Very similar to the Dale Carnegie course. I think it really helped me, as a young woman, get through a tough time in my life. I don’t remember it being particularly religious in any way, but to this day I remember their motto:

I can’t lose – why? I’ll tell you why! I have faith, courage and enthuuuuuusiasm!

Reply

Alfred Gade - 1963 JD

Enjoyed reading about the early history of Detroit and the bravery of it’s Priest, Fr. Gabriel Richard. A man who lived his Oath of Allegiance to his Church and his Country in both word and deed. Everyone, including the Indian native people and Protestants, respected him. At least until today, no one has tried to say otherwise. He, along with Detroit’s Saint Fr. Solanus Casey, seemed destined to serve and save Detroit.

Reply

Parmeshwar Coomar

This a beautiful story of a man inspired by God and faith to found an outstanding place of learning and knowledge. Michigan must raise a statute to his honor for posterity to know of this man and his works for all humanity.

Reply

Sharon LaQuey

At a Lutheran Church in Illinois there was a class with the name of Gabriel Richard teaching people how to speak up in public about things that would make a difference. For people who were unable to usually speak publicly.

I am wanting to find out more about that program.

Reply