Sheryl White arrived at U-M as a freshman in the fall of 1972, just two years after the tumult and transformation that came with the Black Action Movement (BAM) strike of 1970, which led to new goals for African-American enrollment and enough student aid to meet them. She was 17.

She had been the valedictorian of Detroit’s Kettering High School. She came to Ann Arbor as a Regents Alumni Scholar—and found herself in a brave new world.

“There was an awareness on my part that this was a great opportunity, but I was also aware of the circumstances by which I was there,” she remembered recently. In other words, she knew she was part of the post-BAM cohort of African-American students, recruited in the wake of controversy and under pressure to show their academic mettle.

“I knew that I was, quote-unquote, a ‘good student’—valedictorian, inducted into the National Honor Society, perfect 4.0,” recalled White, now Sheryl Barnes. “But I was still coming from an urban high school. I got to U-M and I thought I was smart—and then I met students who had had, like, four years of physics, two or three years of statistics! There was a differential. It was cultures clashing; it was a redefinition of what is ‘smart’; it was running into different cultures where you’re accepted and different ethnic groups where you’re not; not seeing many teachers who looked like me; having my abilities questioned; and then at other times having my abilities encouraged and embraced. So it was this mixing bowl of all kinds of things that affect a young person, and it was messing with my head.”

A lustrous purpose

Barnes had been editor of Kettering High’s yearbook—she’d been shooting photos since she was 13—but after flirting with the idea of a journalism major, she shifted to psychology, which fascinated her.

Still, she kept an eye on U-M’s student media, and when she paged through the Michiganensian, she said, “I don’t remember seeing enough other students that looked like me. It felt like we were not truly represented.”

So she took on a new project.

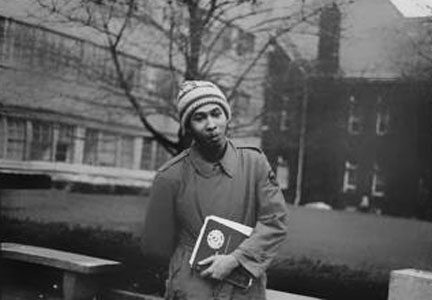

Throughout her senior year, Barnes shot photos of African-American students on campus and around town. In that time long before Facebook, she called friends and friends of friends to ask for photos they’d taken.

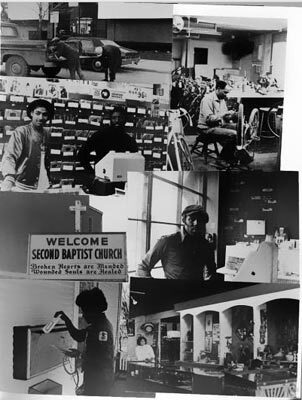

She sought and received help and support from churches and other community organizations; fraternities and sororities; and the University, including the office of U-M’s Black Advocate, Richard D. Garland.

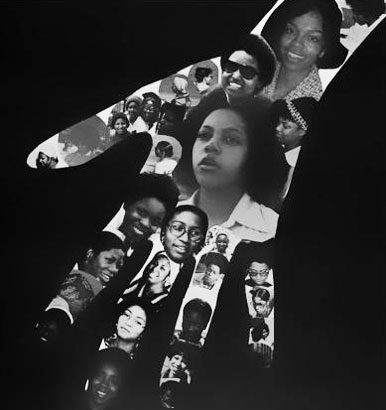

Finally, she assembled all the photos plus some poems into an alternative yearbook of the African-American experience at Michigan. She called it Nia, which means “lustrous purpose” in Swahili.

“For me, it was a masterpiece”

Nia was a homemade affair produced on a shoestring. But the photos capture a deep slice of the Michigan experience in the mid-1970s—students with their noses in books and over a chessboard; students playing cards in somebody’s room or basketball at South Quad; students on the steps of the Union, waiting for the bus; students at church and just hanging out; celebrity speakers like the comedian and activist Dick Gregory.

Photos of African-American students at U-M in the years on either side of 1970 tend to be images of protest and defiance. The images in Niashow another side of those years—the everyday, casual life of black students at work and relaxing. They enlarge the history of that time and place.

The other night Barnes pulled the yearbook out of storage and turned the pages for the first time in years. In our interview the next day, she said: “I almost called you back last night and said, ‘Let’s forget it! There are no page numbers!’

“We typed it. I cut things out and put them on black construction paper. From a production standpoint, it really was crude.

“On the other hand, for me, it was a masterpiece, because it was a validation—without even knowing it—that said: ‘This is who I am.’ The yearbook came out of a need to validate what the University of Michigan experience had been for me… It was a desire to capture the lived experience of other students who were like me.

“The memories, for me, are overwhelmingly positive. There are some that are really horrific—and so what else is new? You deal with it and you move on.”

She moved on, all right. The industry she showed in college only picked up steam beyond U-M. After graduating with a degree in psychology, Barnes hung out a shingle as a graphic designer. That work turned into her own advertising agency, and along the way she earned a master’s degree and two doctorates. She also earned a seminary degree (DMin), so she is now the Rev. Dr. Sheryl L.W. Barnes. Her adult son, Kyle Hunter, still lives in Ann Arbor. In the mid 2000s, marriage took Barnes from Michigan to Connecticut, where she is a Bible teacher, faith-based life coach, and author.