Always on call

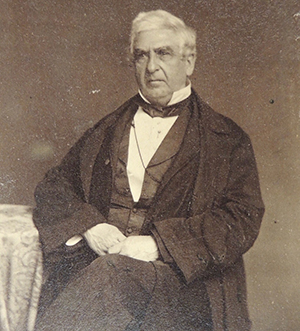

As regent, Pitcher was an early advocate of acquiring John J. Audobon’s “The Birds of America” for the U-M Library. (Image: National Audobon Society.)

When Dr. Zina Pitcher was buried in Detroit’s Elmwood Cemetery in the spring of 1872, his eulogists had a lot of talking to do. In his 75 years, Pitcher had accomplished an extraordinary number of things.

He had been Michigan’s most prominent doctor. He established a system of public schools in Detroit. He was president of the U.S. Army Medical Board; co-founder of the Michigan Historical Society; and president of the American Medical Association. He wrote scientific articles on epidemics, meteorology, and Native American medicine. He taught at West Point. He was mayor of Detroit three times, and as the Whig Party’s nominee for the statehouse in 1844, he was nearly elected governor of Michigan.

Then there was the critical role he played in the University of Michigan’s early years in Ann Arbor. Of the 12 original regents appointed to set the new institution on its feet, he served the longest and arguably worked the hardest. And his fascination with the natural sciences gave shape to the University’s earliest ambitions for greatness.

Doctor on the “savage frontier”

At the age of 5 in 1802, Pitcher had seen his father die young, leaving the responsibility for four boys to their mother, a fierce-willed Scotswoman who was determined that her sons be well educated.

The boys went to local schools in their rural county along the Hudson River in upstate New York. Zina became fascinated by the wild plants in the forests and fields nearby. As he prepared for a medical career, he crammed his off hours with the study of botany.

When he had finished his grand total of two courses in medicine, Pitcher enlisted in the Army as a surgeon. Soon he was serving at garrisons throughout the upper Great Lakes — then “a savage frontier,” one biographer said — at Detroit, Saginaw, Port Huron, and Sault St. Marie, as well as among the Cherokees and Creeks of the Indian Territory (latter-day Oklahoma).In Detroit he made friends with the likes of Lewis Cass, the territorial governor; Henry R. Schoolcraft, a self-taught scientist and authority on Native American tribes; and Lucius Lyon, a future U.S. senator.

After 15 years in the Army, Pitcher opened a private practice in Detroit just as Michigan was joining the Union. He quickly became the city’s leading doctor and one of its most influential citizens — and soon the city’s mayor.

Treating his patients one day, running the city’s business the next, he made time to help launch one of the young state’s fledgling endeavors — the new university in Ann Arbor.

Governor Stevens T. Mason appointed him as one of 12 founding members of the board of regents, charged with hiring a faculty and establishing “libraries, museums, athenaeums, botanic gardens, laboratories, and other useful literary and scientific institutions.”

A school of “the highest standard”

In a later era, with greater educational opportunities, Pitcher likely would have found his calling as a scientist.

As an Army doctor on the nation’s frontiers, he had spent countless hours staring at the native flora, studying seeds, collecting specimens, and conversing through interpreters with Native American medicine men about the plants they used to treat the sick.

In fact, as an amateur botanist, Pitcher had discovered several heretofore unknown species, including a white-to-pale-pink flowering thistle that would later be familiar to beachcombers throughout the Great Lakes. (It would be called Pitcher’s Thistle [Carduus Pitcheri or Cirsium Pitcheri],one of four plant names that honor Pitcher’s discoveries.)

His fascination with the natural sciences paid dividends in Ann Arbor when the regents came to the business of hiring professors. Early on, they recruited Asa Gray, a young physician and scientist who had become a protégé of John Torrey, the nation’s leading botanist. Gray and Torrey co-authored the definitive Flora of North America.

Two regents had corresponded with Torrey on botanical matters — Henry Schoolcraft and Pitcher. When they asked Torrey whom they should hire as a professor in the natural sciences, he recommended his collaborator, Gray. Arriving in Michigan, the rising star’s first stop was at Pitcher’s home in Detroit.

Gray accepted the job but told the regents he first needed one year to continue his studies in Europe. The regents were fine with that; they had yet to build a single classroom building. Still, they had an important assignment for him. They gave him the task of purchasing books for the University while he was abroad. He did so, shipping some 3,700 volumes to Ann Arbor.

Gray was never to teach a class at Michigan. Harvard hired him away before the first courses were offered, in 1841, and he went on to become the nation’s premier botanist. But his botanical connections to Pitcher and Schoolcraft led to the establishment of the University library, which in turn drew even more scholars to U-M.

Founder of the Medical School

Pitcher, appointed to four successive four-year terms, was the most active and influential of all the early regents. As Dr. Frederick Novy, a major faculty figure of a later era, put it long afterward, “his gentlemanly demeanor, upright character, and conservative opinion” made him the first man other regents turned to when important plans were to be made and executed.

Pitcher’s most significant work was the founding of what would become the Medical School.

This was no easy matter. Medical instruction had been envisioned in the University’s founding documents. But — thanks to the Panic of 1837 and an ensuing economic depression — funding was scarce and 10 years passed before a working medical department was even proposed.

When an early plan stalled, it was Pitcher who pressed the case hard, arguing that Michigan’s fast-growing population, fueled by immigrants, was desperately in need of trained doctors. He showed that dozens of native Michiganders were getting medical training in other states and likely to stay there. The state could not afford such a “brain drain.”

Pitcher won the day, and in 1850 the University launched a medical department. (It would be nine years before a law department followed.) He hired the first five medical professors and wrote the rules for the nascent department. (The new faculty members promptly honored Pitcher by bestowing on him the honorary title of professor emeritus of medicine and obstetrics.)

Pitcher pushed for U-M’s first clinical instruction, and he helped to open a clinical summer program for medical students in Detroit. But he was also the chief opponent of a proposal to transfer the entire medical department to the larger city, insisting that splitting the University in two would be “a crime.” Again, he prevailed, and the campus remained united.

Flowers on a grave

In failing health, Pitcher retired from medicine in 1871 and died the following spring. For many years his memory was honored, quite fittingly, with flowering plants. The reason went back a long time.

In the early 1840s, a boy with a badly broken arm had been brought to Detroit from northern Michigan. Untreated, his condition had grown so grave that the doctor he saw prepared to amputate.

At the last minute, when the boy was strapped down for surgery, Dr. Pitcher was consulted. After a careful examination, he asked if he might try to save the arm. Pitcher’s intervention succeeded.

The boy, Peter White, grew up to be a regent of U-M himself, and long afterward, he saw to it that Pitcher’s grave in Detroit was planted with blossoming flowers every spring.

Sources included Frederick Novy, “Zina Pitcher,” Michigan Alumnus (April 1908); Bill Collins, “Dr. Zina Pitcher — Bandages, Beaches, Botany and Ballots,” Lakeshore Guardian; “Dr. Zina Pitcher,” Detroit Free Press, 4/6/1872; Zina Pitcher, “A Memoir,” National Library of Medicine; Ralph D. Williams, The Honorable Peter D. White (1905).

Margaret Bennett - 1958, 1975

I am writing a book about Michigan pioneers after the War of 1812: ‘A Michigan Appetite.’

Zina Pitcher is mentioned in a chapter on The Treaty of Saginaw, when he was with Fort Saginaw. This story adds a lot to my chapter.

Would like to add a footnote about some of Pitcher’s other accomplishments.

Thanks!

Good story!

Reply

Brian Wiatrak - 1980

Fascinating. I know the name, but not the story behind it. Thanks for publishing!

Reply

Richard Futyma - 1977, 1982

Anyone interested in reading more about the botanical contributions of Zina Pitcher, as well as many of the other early natural scientists in Michigan’s history, including Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, would do well to read “Botanical Beachcombers and Explorers: Pioneers of the 19th Century in the Upper Great Lakes,” written by long-time U-M professor of Botany, Edward G. Voss. (Contributions from the University of Michigan Herbarium, Vol.13, 1978, 100 p.)

Reply