Matthaei’s magical, mystical agave

A poignant scene draws to a close at U-M’s Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum as an 80-year-old American agave blooms for the first — and last — time in its majestic life. This American agave arrived at U-M in 1934, the same year a University task force declared the arboretum would “become a haven of quiet one hundred years from now when our rich native flora will have become a thing of the past in most places.” (Images courtesy of Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum unless otherwise noted.)

-

A life worth living

U-M created the botanical garden and arboretum in 1907. At that time, the property consisted of approximately 80 acres. Today, the staff manages more than 700 acres around the Ann Arbor area with a complex of conservatory, greenhouses, laboratory, teaching, and meeting spaces at Matthaei Botanical Gardens and the James D. Reader Jr. Center for Urban Environmental Education at Nichols Arboretum.

-

Growth spurt

University of Michigan grad student Alfred Whiting collected this variegated American agave (Agave americana) in Mexico in 1934. The American agave usually blooms in nature at 10 to 25 years of age. But this Ann Arbor transplant took its sweet time. In spring 2014, the 80-year-old plant surprised everyone by suddenly sporting a flower stalk that started growing nearly six inches per day.

-

Late bloomer

“No one knows for sure what combination of environmental conditions induces the American agave to begin flowering,” says Mike Palmer, horticulture manager at Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum. “And it’s rare for one to bloom indoors. Of course, being in a conservatory helps!”

-

We are family

This American agave is native to the Southwest United States and Mexico and is an example of a plant species that’s well adapted to dry or desert conditions. The American agave is now planted throughout the world as an ornamental in arid regions. This one likely was planted in the ground bed of the conservatory on Dixboro Road in the early years of the U-M’s botanical gardens. And if you think the flower spike of the American agave looks like a giant asparagus spear, you’re on to something. The plant is in the asparagus family.

-

Things are looking up

American agave foliage is usually three- to six-feet tall and six- to 10-feet wide. The flower stalk can reach up to 30 feet tall. The American agave is often referred to as the “century plant,” probably because humans have noticed (and then exaggerated) how long it takes the plant to mature and flower. That said, this one did take almost a century!

-

Gonna take you higher

In May, the stalk was more than 20 feet tall, requiring workers to remove a pane of glass from the conservatory ceiling that would allow the stalk to continue its upward climb.

-

Drinks all around

While many know agave as the source of tequila, the fiery distilled beverage is made only from the tequila agave (Agave tequilana). In areas of Mexico where tequila is produced, the American agave is used to make a similar alcoholic drink called mezcal. The flower stalk of the American agave can be cut before flowering to produce aguamiel, a sweet liquid collected at the base of the stalk. This liquid can be fermented to make a drink called pulque. Additionally, fibers gathered from within the leaves are used for making rope or twine.

-

Through the roof

This enormous and impressive plant may be gorgeous as it climbs through the conservatory’s roof, but the plant is actually in the process of blooming, setting seed, and dying, Palmer says. The joy and sadness of the agave are inseparable, it appears. Joseph Mooney, manager of marketing and public relations at the Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum, describes the plant’s unexpected display this summer as “operatic.”

-

View from the top

An overhead view of the agave, blooming above the conservatory. Looking pretty good for 80.

-

Blurred lines

The agave’s sinuous leaves, bristling with spikes, begin to wrinkle as the plant succumbs to the not-so-subtle effects of dying — or, as Mooney puts it, “transitioning.”

-

Sweet!

Despite the aging down below, life above the conservatory roof is booming, as area hummingbirds enjoy the flowers blooming above the glass. Along with bees, wasps, and moths, the tiny birds perform most of the heavy lifting in the pollination department. A Mexican long-nosed bat takes the pollinators’ night shift in the plant’s natural setting. (Photo: Glenn Hieber.)

-

Pollen grab

Chris Edwards is manager of the Microscopy & Image Analysis Laboratory, part of the Biomedical Research Core Facilities in U-M’s Medical School Office of Research. He is collecting pollen samples from the agave to review under the lab’s AMRAY 1910 Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope.

-

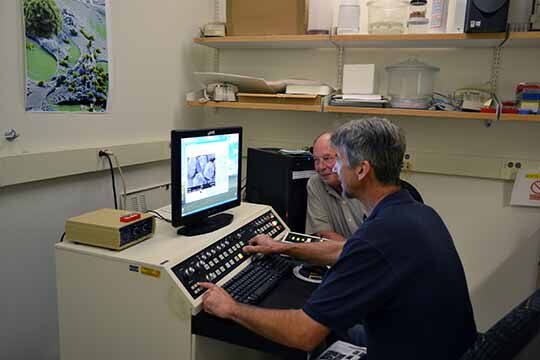

Scanners

Back at the Medical School, MIL’s Edwards assists Matthaei’s Palmer (foreground) as they examine highly magnified images from the 80-year-old agave using the lab’s powerful scanning electron microscope.

-

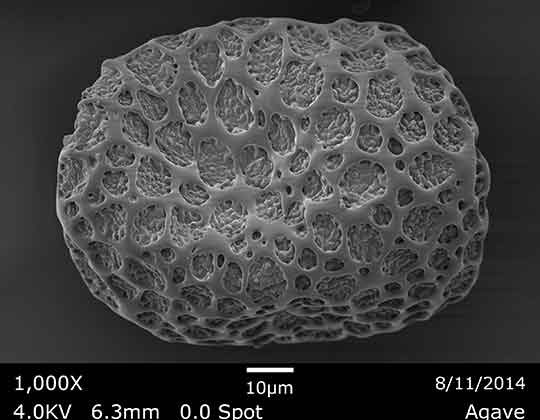

Ready for your close-up?

This microscopic image of agave pollen demonstrates the powerful technology at work in the Microscopy & Image Analysis Laboratory. Are your eyes watering yet?

-

Seed me

The American agave produces hundreds or even thousands of seeds that have the potential to grow. “In the harsh, low-water environment of the desert, plants must produce many offspring to get a few progeny that will reach adulthood,” Palmer says.

-

Floor show

It appears that fewer than 50 percent of the aging agave’s flowers are setting seed. Many of the spent flowers have now fallen to the conservatory floor. Up above, the conservatory’s roof glass around the stalk is grimy with pollen and nectar that has dropped from the flowers.

-

Happy ending?

While undeniably beautiful, the flowering process is poetic and somewhat tragic. At its conclusion, the 80-year-old American agave will die. Or will it? The parent plant actually produces propagules (clones) throughout this process. “Pups” are clones that form at the base of the agave plant and “bulbils” are clones that form on the flower stalk. So, if all goes according to plan, life will go on for Alfred Whiting’s variegated agave, after all. Stay tuned.