“Every poem I write is for me, in Whitman’s phrase, a ‘language experiment’ and a process of discovery … I write slowly and painstakingly; often work on a poem several years, revising even after publication … I think of the writing of poems as one way of coming to grips with inner and outer realities—as a spiritual act, really, a sort of prayer for illumination and perfection.”

— Robert Hayden

A poet’s poet

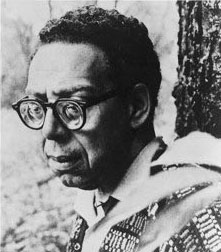

Robert Hayden, MA ’44, was many things: an educator, a spiritual seeker, a Detroiter. But more than anything he was a poet. And not an African-American poet. Not even an American poet. But simply a poet, whose work was characterized by a profundity, a humanism, and a linguistic versatility that propelled him to national acclaim as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (now known as Poet Laureate to the United States).

In November, the late alumnus and U-M professor was celebrated at a centennial conference attended by scholars, poets, former students, and friends impacted by his creative legacy. His canon includes such powerful works as “Middle Passage,” “Those Sunday Mornings,” and “Elegies for Paradise Valley.” The latter, written as a tribute to the Detroit neighborhood where Hayden was born in 1913, demonstrates the artist’s signature style: an incomparable sense of milieu with uncanny attention to character and setting.

“He was a poet who understood human nature and he had the linguistic power and ability to summon states of being and states of mind that rank him as one of the major poets of our time,” says Laurence Goldstein, professor of English and co-editor of Robert Hayden: Essays on the Poetry. “Through the years Robert’s poetry got larger in scope and more capacious in themes. He is just now beginning to garner the kind of critical acclaim he long deserved.”

In a word

Hayden was a precisionist who used language sparingly and to great effect. The craft did not come easily to him; he was not a garrulous poet who wrote voluminously.

“He was very selective in what he published; as a result he never missed,” says poet Lawrence Joseph, AB ’70/JD ’75, Tinnelly Professor of Law at St. John’s University School of Law in New York City and author of Codes, Precepts, Biases and Taboos: Poems 1973-1993. “Almost all of Hayden’s work is major work. He was that sophisticated, that smart.”

Through such pieces as “Mourning Poem for the Queen of Sunday” and “Summertime and the Living,” Hayden produced a vivid historic record of old East Side Detroit in the early 20th century. “Through wonderful detail and elevated language he captures the cultural milieu that so delighted him; the vitality of it,” Goldstein says. “There was a kind of dynamic relationship between himself and these people who taught him to endure, and even thrive, in the midst of poverty and intolerance.”

“I am I”

Born Asa Bundy Sheffey, Hayden was stricken with near blindness shortly after birth and wore extremely thick eyeglasses throughout his life. He was raised in Detroit’s Paradise Valley slum, as he described it (“‘ghetto’ was too romantic for Robert,” says Goldstein), by foster parents who called him Robert Earl Hayden. He was a slight, tenderhearted boy who retreated into an imaginary world brought to life by the Detroit library system. As an adult Hayden was devastated to learn his name never had been legally changed by his foster parents. Robert Earl Hayden technically did not exist. Grappling with the meaning of self became a lifelong struggle from that day forward.

After leaving Detroit City College (now Wayne State University) in 1936, Hayden tried on the role of “people’s poet” during a stint in the Federal Writers Program through the Works Progress Administration. He further developed his voice during graduate work at U-M where he studied with poet W.H. Auden. Hayden would describe his pre-MA writing as mathematics, while the Auden years were more akin to algebra. Auden introduced him to a modern, experimental approach to writing steeped in a universal humanism, and Hayden responded by vetting multiple forms and styles, seeking never to repeat himself. His work could be sentimental, as in his cinematic tribute “Double Feature”; harrowing, as in the epic slave narrative “Middle Passage”; or humorous, as in the encounter piece “Unidentified Flying Object.”

And though he began to gain recognition during the turbulent years of the Black Arts Movement, Hayden rejected any affiliation with any specific group. He risked—and regularly encountered—rejection from artists who sought, unsuccessfully, to claim him. He was inspired as much by W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot, and Gerard Manley Hopkins as he was by Ralph Ellison, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes.

“One of my desires would be not to have to divide Hayden into the ‘black Hayden and the universal Hayden’ or the ‘black Hayden and the human Hayden,'” says Harryette Mullen, UCLA professor of African-American poetry, African-American literature, and creative writing. Her book Sleeping with the Dictionary was a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. “Robert Hayden was and is a poet’s poet,” she says.

The nation’s poet

After winning a Hopwood Award in 1942 and graduating from U-M, Hayden embarked on his career as an educator, first at U-M and then at Fisk University in Nashville. In 1969 he returned to U-M where he taught until his death in 1980.

“He was a wonderful teacher,” Goldstein says. “He put in a lot of time meeting with students, going over their work line by line. He also loved to read his own poetry, and he was very good at it. Students would be very intent on listening to him.”

In 1976 Hayden took a sabbatical from teaching when President Gerald Ford appointed him Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, a two-year post now known as Poet Laureate to the United States. He was the first African-American poet to hold the position. Hayden moved to Washington, D.C., for the duration, where, Goldstein recalls, he spent a lot of time fending off book-length manuscripts from novice poets seeking his critique.

“He was much honored of course,” says Goldstein. “But he was very funny on the subject once he came back. He had a joke that he half expected President Ford to come into his office and pull a sheaf of papers out of his jacket and say, ‘Well, the little lady likes to write some verse now and again…'”

For Hayden, “It was his mission to write poems,” Goldstein continues, “the excitement of it, the psychological and spiritual rewards of getting something right and inventing something that had never been said before in quite the same way. I’m pleased that he lived long enough to receive some very handsome reviews and to see his work appear in the major anthologies. It gave him the sense that his work would survive and be read widely.”

Hayden died of cancer in 1980, as dedicated, determined, devoted, persistent, principled, and ambitious as ever. In 2012 the U.S. Post Office issued a postage stamp to honor his achievements.