A death in Kalamazoo

On a springtime afternoon in 1924, Minerva Moffett walked across the street from her Kalamazoo home to check on her elderly neighbor. Moffett operated a boarding house and the old woman often came by for meals; other days, Moffett took food to her.

Moffett now stared at a tray of food outside the neighbor’s door, cold and untouched from the previous evening. Forcing her way into the house, she found her neighbor on the kitchen floor. Madelon Stockwell Turner, 78, was dead. She died alone, a recluse in a stately home that was one of the grandest in the city.

Her death made headlines for two reasons. She was believed to be the richest woman in Kalamazoo. And a half-century earlier, she was the first woman to enroll at the University of Michigan.

Alone on campus

Madelon Stockwell stepped onto the U-M campus in February 1870. Her arrival from Kalamazoo disrupted a world that had been wholly male since the fall of 1817, when the university first opened in Detroit.

“Who is she? Where is she from? What is her name? What class is she going into? And a thousand and one other questions were asked, with equal eagerness, by ‘grave and reverend seniors,’ and ‘freshmen green as grass,’” wrote the sophomore editors of “The Oracle” within days of her arrival.

She was 24 and the object of curiosity and stares, of whispers and murmurs. Boys not registered for courses she was enrolled in nevertheless slipped into the classroom, hoping to catch a glimpse of her.

From her perspective, everywhere she turned there were men: as classmates, as professors and as administrators. She was the lone woman on a campus of some 1,100 students — one of the largest universities in the country.

To compliment Kim Clarke’s beautifully drawn editorial portrait of Michigan’s first female student, Madelon Stockwell. I decided to interview an author and professor who’s an expert on women in higher education. Andrea Turpin is an associate professor of history at Baylor University. She recently spoke at U of M’s Bentley Historical Library about some of the topics in her book, “Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education”. She covers the years 1837 to 1917, a time when women first stepped onto college campuses as actual students. Listen in as Andrea sheds light on the University of Michigan’s transition to co-education in 1870. There are a lot of things at play you might not realize. Here’s Andrea.

Andrea L Turpin: At the time that Michigan was founded, you know, colleges traditionally served both the church and the state. And state universities did, too. They just reversed the emphasis.

Holdship: Oh ok.

Turpin: So Michigan’s are the state and the church. Traditionally, colleges had prepared male students for one of four professions. So being a minister, being a lawyer, being a doctor or just being an educated gentleman who would typically be a local leader in politics or business. So one of the reasons women didn’t go to college was that they weren’t going to do those things at that time. And so, you know what of the other things that I talk about in the book is “Why did that change—why did women start going to college”?

Holdship: So the book is called “A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education 1837-1917”. So I want to know about the significance of that time period and why you chose it to— to do your study.

Turpin: Yes. So partly I liked ending in sevens both times, right?! 1837 is the first year of co-education in the United States and as far as I know, the world. And it took place in neighboring Ohio, right, at Oberlin College.

Holdship: Yay Oberlin.

Turpin: So Michigan was not that far behind in terms of its original debates in 1858, but then was a bit further behind in actually doing co-education in 1870. So that’s the year that— that’s why 1837. Also, a parallel thing happened in 1837. Mount Holyoke opened and it was sort of the first pre college in a single sex setting for women. Not quite collegiate education yet, but the highest available. And in 1917, the end of World War One, by which time sort of our modern structure of higher education was in place.

Holdship: There was— I came across this sentence that I can’t remember if it’s from you or from one of the reviews I read. But “no college environment is morally neutral.”

Turpin: I wrote that.

Holdship: Yes. I’m so intrigued by that.

Turpin: So one of the things that I explore in my work as I’m looking at why different institutions did or didn’t admit women and how they understood what they were doing, is that that decision, and then also what they trained men and women to do, and what they communicate to students about how they should develop as people, and how they should serve after they graduate, was very much tied to an institution’s understanding of what higher education is for, as well as its vision of what a good American society looks like and how you make positive social change. And so some institutions understood positive social change as coming from the ground up and others from the top down. That had to do with whether they admitted women, whether it had to do with actually religious conversion, getting a bunch of people right with God. Then they get a new heart and then they get right with each other. Or if it works in reverse, you get right with other people. And that’s what makes you right with God. All of these things right, are a vision of what it means to be a good person, what it means to be a good community and what education has to do with that. And so what I was concluding at the end is that different institutions take different tax on this, but they’re all taking a tax. So even an institution that says all we do is provide education for people to do whatever they want, then they’re actually sending a message to students. And it might be that their education does not give them any moral obligation to give back to their community. They can just use it to make money for themselves. So even when we think we’re being neutral, we’re communicating something to students.

Holdship: Obviously, I’d like to focus on Michigan. Our friend, President Tappan, not really keen on admitting women, not as progressive as the president at Oberlin, apparently, who found it all to be a win-win situation, I guess— to have women on his campus. But during that early time, women were attempting to get into school here and they were just getting shut down.

Turpin: So a lot of this had to do with how you think positive social change happens. So Tappan did think that God has a certain order and that men do this and women do this. But Oberlin was founded by a bunch of evangelical Protestants who thought that to get the message out, people needed to convert. So you need to train as many women as men so that more people get the message out. So they actually also took a biblical reason for women’s education and Tappan was against. And the difference was how they thought change occurred. Right. And what made a good society.

Holdship: Once our friend Mr. Angell came aboard?

Turpin: His vision was that an institution is just and basically serves God and serves the state if it provides education to those who are able but doesn’t make any further distinctions. So Michigan was free, right at the time. Except, student expenses were a real thing. So I mean, if you were truly poor, it could be rough. But the tuition was free if you could get in, right. And it’s available to men and to women. They, Michigan, had already admitted a few black students, would do so as continuing as well, though that wasn’t its focus as much as being coeducational and admitting poorer students. So he thought that it was just, it was like God, who freely gives gifts to all people for the state university, to freely give gifts to all people and to train everybody to be their best to go back and serve the public good. By the time you hit the 1870s, the Michigan voters say, we want our daughters to have access to this institution. And it’s a state institution. So finally, the state’s like, fine. And they do it without spending any additional money. So in the 1850s, they said we can’t do it because it would be too expensive. By 1870, there was enough demand that they’re like, “Sure”. But they don’t have boarding houses with wise and pious matrons. They don’t have any regulations about when students come in or go. And so from about 1870 to 1890, Michigan had no regulation of men and women and how they related at all. They sometimes boarded in the same boarding houses in the towns. And this is way— this is like 1960, 70s as opposed to 1950s, when most colleges had regulations about men and women’s hours if they had dorms on campus. President Angell and his successor, President Hutchins, right. Together they served for 50 years and both of them had a relatively sexless vision of how Michigan graduates could serve their communities. So when at sort of a national level, national organizations on campus began to shift in a direction of having very sex specific moral messages about what you should do with your education, that began to affect Michigan students, too. And there’s a second reason, and I hate to diss on Greek life, but fraternities got a lot of power by 1890. And so male fraternities at that point had so much power, they began to control student extracurricular organizations. And from 1870 to 1890, women and men served relatively in proportion with their respective numbers in the student population in terms of officer roles and all sorts of things: religious organizations, literary societies, class government. In the 1890s, fraternities took it over and women were sort of kicked out of mainstream social life in the university. So they began to form, partly by necessity and partly by choice, a separate culture of women’s organizations, and those organizations, partly because of a shift in thinking that was somewhat based in a shift in how religion was understood at the time, that separate culture began to try to carve out a very special place for college-educated women in society. After they graduated, they would — they were urged to go into social service professions like social work or settlement houses where you move in with the urban poor and you learn from them and you help them solve their problems. And the belief was that a college-educated woman, uniquely combined head and heart, that women had this more emotive side and that that gave them a special place in fixing some of the problems that were arising in the United States from industrialization and urbanization. And this was good for women in one sense. It gave them a vision of what they could do with their education besides being a mother or being a teacher which were the accepted things up till then. But it was bad in another sense in that it channeled them into sort of a narrow set of occupations and it sort of pressured men not to try these new occupations because they were seen as feminine more and to just do volunteer work on the side.

Holdship: So do you know much about our Madelon Stockwell who came here?

Turpin: I do know of it.

Holdship: So talk a little bit about her and why she, you know, just made such a difference.

Turpin: To me, one of the interesting things about Michigan’s story is that the very first— that there was a first woman, right, to attend rather than first women.

Holdship: Yes.

Turpin: Right, so can you imagine being the sole woman?

Holdship: No.

Turpin:

You’re in a class, not just in a class. I’ve done that. I’ve been the sole woman in a class, but an entire institution. And you really have to have the pioneers or the people who are. It’s worth it to them. And they have the personality or the support system. Right, to do it, even when they don’t have other people like them there.

Holdship: Eliza Mosher then, also came through becoming the first dean of women and at her own insistence, the first female professor.

Turpin: And Angell did support that as well.

Holdship: So-

Turpin: And so she taught both men and women, which— so he did not say you just teach health to the women. Eliza Mosher, as most people at Michigan know had an M.D., right? So she came on as the first female professor and a doctor. But the medical school wouldn’t take her. They wouldn’t appoint her because they were unwilling to appoint a woman. So as a doctor, she was appointed to the literary department, though she taught health to both male and female students, which is kind of crazy.

Holdship: The patience these women had to display. All right. So what you said— you were speaking to some students yesterday and what, what are you finding students are most interested in about your work?

Turpin: The history of higher education is useful for all students because it helps them reflect on, “Why am I here, what am I doing”? Oftentimes in the United States today, we go to college because it’s the thing that you do. But it wasn’t, in colonial America, one percent of men went to college, it was not the thing you did. And so understanding, you know, what has changed in American culture. It can help students, I think, be reflective on how they want to use their education and how they can use it to serve others.

Holdship: Interesting stuff, yes? I hope you make it over to heritage.umich.edu to read Kim’s complete story about Madelon Stockwell. The piece I’ve got here is just a teaser. Thank you so much for listening. You can find ListenInMichigan under the podcast tab at michigantoday.umich.edu. Or find us and subscribe at Spotify, Google Play Music, iTunes, TuneIn, and Stitcher. Catch you next time. And as always, Go Blue.

(The podcast above features Andrea Turpin, author and professor of history at Baylor University. She is an expert on the advent of co-education at the college level. Listen in, as she describes the evolution of campus culture at U-M.)

Cold shoulders and hot rhetoric

Stockwell had attended Albion College, where she graduated with a two-year degree in 1862. She then watched as male classmates from Albion moved on to Ann Arbor for more schooling. She once visited U-M and overheard a professor remark “that he did not think young women would be able physically or mentally to bear the strain of higher education.”

“My heart sank,” she wrote.

Regents, presidents, and professors had argued for years about admitting women, and settled on an all-male university rather than deal with the potential “corruptions” they believed came with women on campus. Taxpayers, however, began to agitate for the education of their daughters as well as their sons. A state university funded with public dollars, they argued, should be open to all.In January 1870, the Board of Regents passed a one-sentence resolution that would forever alter the institution: “That the Board of Regents recognize the right of every resident of Michigan to the enjoyment of the privileges afforded by the University; and that no rule exists in any of the University statutes for the exclusion of any person from the University, who possesses the requisite literary and moral qualifications.”

Living with loss

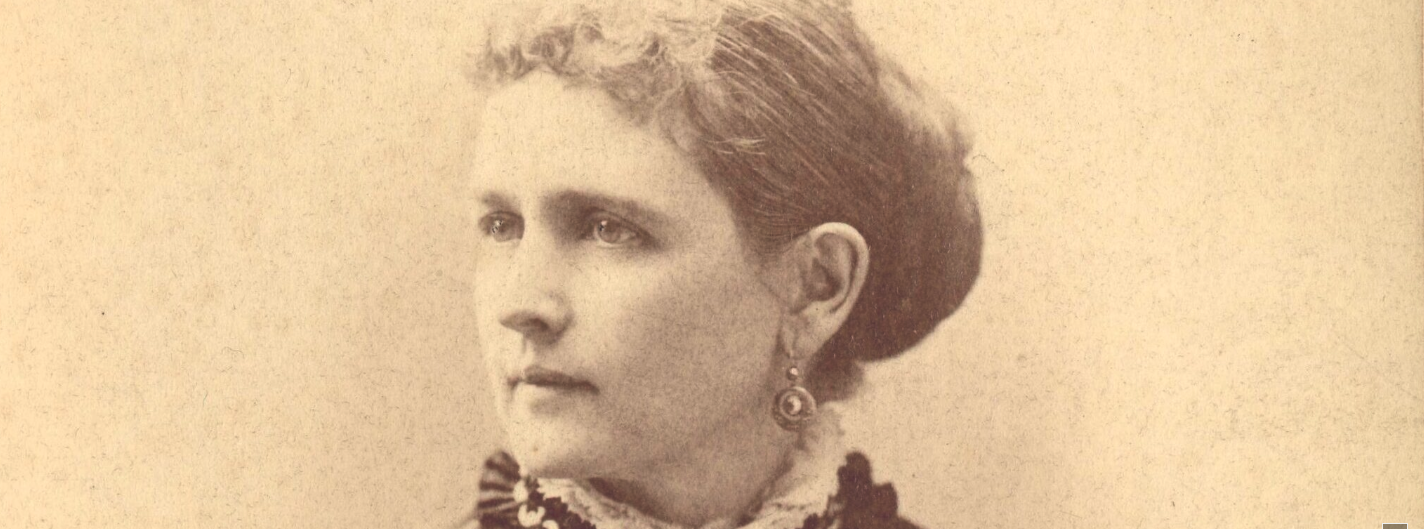

Madelon Stockwell and her mother, Louisa Peabody Stockwell, circa 1850. (Image: Albion College Archives and Special Collections.)

As a child, a U-M undergraduate, an adult, and an elderly recluse, Madelon Stockwell lived in a world of books. Her contemplative environment helped diminish a constant companion: grief.

Her father died as she neared her fifth birthday. As an adult, she watched as her husband fought a losing battle against tuberculosis. Charles K. Turner had been a classmate at U-M and they married in 1873, the year he received a law degree and a year after she graduated. He died in 1880.

As a widow, Madelon lived in Kalamazoo, where she had grown up. She busied herself with the Ladies Literary Association, giving talks on Greek history, life, and culture. She painted porcelain and entered her work in the state fair. And she excelled in finance, buying and selling real estate and investing in mortgages, to parlay an inheritance into a sizable fortune.

Her business savvy became apparent when her will was unveiled in 1924. Real estate, bonds, mortgages, securities, and cash amounted to $340,000 — roughly $5 million in today’s dollars.

She gave $10,000 for a U-M loan fund to support LSA women with financial needs. The bulk of her estate went to Albion College to establish the Stockwell Memorial Library.

Late in life, Madelon Stockwell Turner wrote a letter to her classmates. She said she knew her solitary studies might “seem somewhat dusty” and appeal to few. But that, she said, was not the point.

“Any pursuit whatsoever, that is really worthwhile, and that takes hold of the eternal verities, adds to the sum of personal knowledge and enjoyment — though gradually, as the dew gathers, drop by drop, in the heart of a rose.”

(Read the complete story of Madelon Stockwell at the Heritage Project. The top image of a young Stockwell is courtesy of Albion College Archives and Special Collections.)

Susan Weiss - 1966

I did not know about this pioneer woman. Thank you for the article about her. And I’m delighted that you did not once mention that she was a good looking woman as so many articles about women often do!

Reply

Deborah Evans - AB, 1981 and AMLS, 1983

Thank you for this wonderful article! I was a resident staff member at Stockwell in the early 1980s, when the building was a women’s only residence hall. I enjoyed reading more about the building’s namesake and feel a little sad she suffered so much loss. Her accomplishments are truly noteworthy.

Reply

Judy Birk - 1982

The article did not mention the beautiful Stockwell Hall named as a tribute to Madelon. It was and remains a spectacular residence for students and was my home for the first two years on campus.

Reply

Doris Rubenstein - BA 1971

The classiest place I ever lived in. I loved just sitting in that elegant formal lounge and staring at the enormous oak fireplaces.

Reply

Gwen Hejna - 1970, 1975

Thank you, Madelon, for starting the gender revolution at U of M. It must have been difficult to be a “freak” in the University classrooms and lonely as the only woman on campus. I enjoyed living in Stockwell Hall as a freshman. Knew nothing about you at that time. My, you are both elegant in appearance and intellect.

Reply

Sarah (Sally) Greek Hitchcock - 1955

So glad to know that Stockwell Hall was named for such a pioneer. I transferred to Michigan back in the “50’s for two of the most jam packed two years of my life. Averaging a 22 hours a semester, and a summer of classes, I was able to graduate with a very average batch of grades, but….have been able to be one of the most independent, community minded people in my small Alaskan town. I learned political activism at Michigan, and all of the courage to start and run my own Piano Studio for over 40 years, as well as raise my three daughters continuing to learn new things about music teaching as I went. I owe so much to those two years.

Reply

Doris Rubenstein - BA 1971

I lived in Stockwell my sophomore year (’68-’69). I was awarded a Stockwell Scholarship at the end of the year for my active participation in dorm activities — pouring tea at faculty receptions; serving on the “Judish” committee, etc. It was $100, but that went a LONG way at that time! It also was an extra flourish on my early job search resumes. It was a conversation starter and I would tell how Madelon Stockwell was the first woman accepted at Michigan. Proud to be associated with her.

Reply

VIRGINIA ANDERSON - 1952

Great article. I lived in Stockwell hall my first year at U of M fall of 1948. I also grew up in Kalamazoo. I never

knew that she grew up there. I was an Honor student at Kalamazoo Central high and had a scholarship to them U of M. I am wondering if it was perhaps from her. I was a math major and all my classes were in the Engineering School with all men so I can appreciate her situation with the whole university being men. My father was Lowell A. Swanson and had his own real estate company selling homes and doing appraisals. He was on many nationwide appraisal boards and usually had a meeting to visit me in California where I moved after graduation. I am interested in where she lived. Most of my life we lived at 833 Lay Blvd. right next to an elementary school and Washington Jr. High. I was born 12-8-1930, so 89 now. In Ca. I first worked for the Jet Propulsion Lab in La Canada, then Lockheed in Burbank and then 49 years selling real estate with Coldwell Banker in Newport Beach following in my dad’s footsteps. I am an AVID U of M. football fan. During the season I have my popcorn, my flag out, and watch all games pretending I am there in person. I go by Ginny here in Ca. Would love to hear from anyone else with contacts in any of these areas. My email is ginny4a@sbcglobal.net.

Reply

Gary Lincoln - 1971 (BA); 1973 (MA)

In 1969 the men of Gomberg House in South Quad and the women of Stockwell came together to enter a Homecoming Float named “An Amazing Delivery.” It consisted of a mechanized stork carrying a bouquet of roses, with the electronic scoreboard reading “Michigan 49, Wisconsin 0.” It won 1st prize in the competition. It was also noteworthy that 1969 Bo’s first year as football coach.

Reply

Susan Zabriskie - 1979

Thank you for letting us all know of this trailblazer. And a glimpse into the whole of her life.Inspiring!

Reply

Pauline Costianes

I’m from Albion and it was founded by a pioneer from New York named Peabody. She had to be related! I also went to Albion College and had no idea that the library was named for her. Wow!

Reply

Kim Clarke

Madelon’s mother was Louisa Peabody, whose parents, Paul and Eleanor, settled Albion.

Reply

Laura Heinrich - AMLS, 68, MA, 70, PhD, 72

This is a heartbreaking and amazing story. In 1970, when applying to a PhD program in Education, I was told by the chairman of the Department that in spite of success in 2 Masters programs – “There is no place for women in Higher Education.”

Reply

Margaret Gruber - Graduated from Albion 1965

Had no idea that the Albion College Library was named after her, and that she had attended there!

I live in Ann Arbor, MI and new that Stockwell Hal was named for her.

Thank you for the rest of her history & accomplishments.

The sad part of her life, to me, was that she had to die alone!

Reply

Sandra D Smith - 1960

Very Interesting to learn about this wonderful women along with her life story ,and the hall on campus that was named after her that was my home for 2 years .

Reply