A barstool ambition

1917: Crews begin construction on the Michigan Union.(Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Late one night in the spring of 1903, a Michigan junior named Bob Parker had a big idea.

Admittedly, he was a little drunk.

He had spent a long session down at Joe’s, a saloon on Main Street much frequented by students. Now he was back in his boarding house on Lawrence Street. (Fittingly, it was Miss Gagney’s house, the one in which a music professor named Charles Mills Gayley composed Michigan’s alma mater, “The Yellow and the Blue.”)

Parker and his pals had been griping, not for the first time, about animosities between fraternity men and “independents,” between the seniors and the juniors and the sophomores, between the Lits and the Meds and the Laws. Why couldn’t they all just rally around Michigan itself?

What could be done? Parker asked himself.

“We wanted an organization ‘for Michigan men everywhere,'” he recalled long afterward, “an organization that would be the one recognized all-inclusive medium to tie up the loose ends, to centralize the campus life, to bring us all together as Michigan men.”

Unlike most ambitions conceived on barstools, Parker’s survived the coming of the next day. Eventually, the idea was turned over to Irving K. Pond, a gifted, slightly eccentric architect who embodied Parker’s notion in the blueprints of a great building.

Both men, the student and the architect, were acknowledging a new reality.

From colonial times through the mid-1800s, there had been essentially two sorts of American colleges — finishing schools for sons of the wealthy and seminaries for ministers in training. Then the University of Michigan and its peers — the early public universities — opened the doors wider. They invited more students to be schooled for an urbanizing, industrializing society.

From 1850 to 1900, Michigan swelled from a few dozen students to several thousand, and the number was climbing fast. Those new students built a world separate from their professors’ classrooms and labs — a hive of societies and clubs, organizations and teams. In the new century, going to college now meant competing in a social sphere that would prepare students for the milieus they would encounter in business and the professions.

Parker the student and Pond the architect embraced that new reality and proposed to enhance it — Parker with a sprawling organization, Pond with a grand edifice.

The organization and the building would carry the same name: The Michigan Union.

Today people say the name and think only of the building. But the building never would have come into being without the organization. Bob Parker’s era is long gone. But the building is the physical remnant of that early-1900s movement to forge a new ethos for the “Michigan Man.”

Segregation by sex

In 1916, wrecking crews took down the old Cooley homesite in order to build the Michigan Union. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Bob Parker tried his idea on a few friends. They liked it. He sounded out President James Burrill Angell, who gave his blessing. Next, Parker took the plan to his fellow members of Michigamua, a new honorary society of leading senior men. They endorsed it, spread the word in their circles, and hosted early meetings.

Parker enlisted several young professors, including the hard-charging Henry Moore Bates, who had just joined the law faculty. Bates had been quoted as saying that the campus needed “a common meeting place, not only for the material conveniences but also as a social and intellectual clearing house.” He became an energetic supporter.

It never occurred to Parker and his allies to include women either in the planning or the organization. That merely reflected the segregation by sex that prevailed across the campus.

Only males had attended U-M until 1870, when a handful of women were admitted. In that era, there were no dorms. For a time, both sexes conducted their lives outside class without University supervision and freely mixed. Men and women often lived in the same boarding houses and broke bread together.

But in the 1890s, when women made up 20 percent of all students, an informal alliance of feminists and faculty wives organized a Women’s League to offer female students their own organizations and activities. Soon women students were guided into female-only boarding houses approved by the League. A dean of women was appointed to supervise them.

By the time Bob Parker enrolled, male students lived in one sphere, women in another. They met and mingled only in classes and closely supervised social settings. Men dominated the major student organizations. The University, with its virtually all-male faculty, was still organized to educate men for an adult world in which they led the institutions and filled the ranks of business and the professions. Women, with few exceptions, were expected to move into the private sphere of home and family.

So when Parker ruminated about student rivalries and antagonisms, he thought only of men, and his solution was an all-male solution.

‘A great club and center’

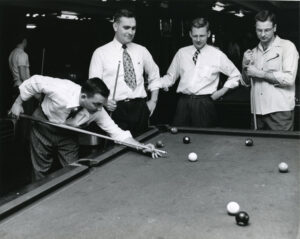

Sadly, the Billiards Room fell victim to the times. During a recent renovation the space was transformed into an idea hub for students to convene. Rest assured, it’s always crowded. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

The idea was to provide “a great club and center for all student, faculty, and alumni activities.” It would draw in “all the societies in the University that care to affiliate with it” — not to govern their affairs, but to act as a coordinator and clearinghouse.

The club would need a clubhouse, a place for rest and recreation. That was the concrete goal. But the campaign to build a headquarters for the union of student organizations was meant to engender a more profound ideal. By bringing groups together to create a physical home for student life, the Michigan Union would engender a unifying “school spirit.” It would bind students and alumni to the University as patriots are bound to their country. In turn, it was hoped, tensions would dissolve between fraternity men and “independents,” Lits and Laws, the class of ’03 and the class of ’04, and so on.

“Primarily, we are here for work,” declared the editors of The Michigan Daily, who approved of Parker’s campaign, “but there ought to be a place in which the men of several departments could get together and become better acquainted… Unless a man is a fraternity man at Ann Arbor he has no very strong ties to bring him back to his alma mater in after years. A Union of this sort would tend to unite the spirit of the entire college, and would become in time as great a factor as athletics in keeping and bringing the men together.”

Parker and company plastered the campus with signs to advertise a mass meeting in Waterman Gymnasium. Eleven hundred showed up to join — a substantial portion of the whole student body — and the Michigan Union was launched. Articles of association were drawn up. Parker was elected the first president.

Fundraising ensued. Members paid annual dues of $2.50. They put on a carnival (later Michigras) in Waterman Gym and sold tickets; they staged shows and held dinners. Well-to-do alumni were targeted, though Parker beat back the idea of soliciting a handful of major gifts from millionaires. Instead, he wanted as many alumni as possible to take shares in the campaign.

At the same time, alumni were raising money for what would become Alumni Memorial Hall to honor the University’s war dead. (That building now houses the U-M Museum of Art.) This campaign confused matters and slowed the Union’s drive. But by 1907, there was enough money to buy a temporary home.The Union chose a broad fieldstone house with three towering gables on the west side of State Street looking eastward down South University. For many years it had been the home of Thomas McIntyre Cooley, dean of the Law School and a justice of the Michigan Supreme Court. Remodeled by Professor Emil Lorch of the Department of Architecture (with crucial funding from Levi Barbour, a wealthy Detroiter and U-M regent), it had two dining rooms, a reading room, a large lounge, and rooms for games and meetings.

It opened as the first headquarters of the Michigan Union in November 1907, and it soon swarmed with events and activities — dinners, receptions, lectures, parties, and meetings by the dozen every month. The Union hosted visiting dignitaries. It organized a student council. It launched the student-run Michigan Opera. Professor Bates, who remained the Union’s chief supporter on the faculty, claimed that after only a few years, it was “conceded to be the most powerful, the most energizing and the most helpful factor in University life.”

The Cooley house was not big enough for the purpose. But it would do while the Union moved on with its grandiose long-term plan.

… Continue reading at heritage.umich.edu. Scroll to Chapter 4, “The Wide Pond,” to pick up where we left off. Then come back and leave us a comment if you are so inclined. We always love to hear from you.

Gregory Havrilcsak - Flint ‘78

A storied history of a storied institution.

Reply

Joaquin Rodriguez Garcia - 1963

I spent long hours at the Union and believe me, next time I come to Ann Arbor, that will be the first place I will visit. It brings me a lot of memories.

Reply

Yury Chernykh - 2009

This is a great story. Thank you very much. In my University of Michigan years, I would come to the Union to sit by a fireplace and listen to piano music performed by a casual player. Or I would forget the time immersed in a book in a cosy chair in one of the beaufully decorated room of this great building. The Michigan Union is really an indispensable part of my Michigan education and experience.

Reply

William Taylor - 1965 and 1970

I grew up in Ann Arbor in the 1950’s and my father used to take me to the Michigan Union to bowl and to swim when I was a teenager. He had a lifetime membership in the Union. He had graduated in 1925. It is interesting to read about its origins.

Reply

Yee C. Chen - 1965 LSA

The Michigan Union held the most fond memories for me when I was a student in UM from 1962 – 65 as I spent many hours there. I was also a member of the then Student Government Council and had many meetings there. As a 3 generation Michigan family I had visited the Union over the years. My last visit to Ann Arbor was in 2019 but unfortunately could not enter the Union as it was closed for renovation. Nevertheless I donated a small sum towards this project and hope to visit again soon.

Yee C. Chen from Singapore.

Reply

Deborah Holdship

You must come back. The building is more beautiful than ever!

Reply

Jo Shaw - 1950

My friends and I may have been the first females employed at the Union. It was 1943, we were 14 and were preparing to start our sophomore year at Ann Arbor High. They must have been desperate because of the lack of men available during WWll. We bussed dishes in the cafeteria. I worked there through high school, advancing to orange juice squeezer, pie server and even waitress for the football team’s pre-game meal. Of course we had to enter through the side door!

Reply

Ken Ware - BS'61, MS'63, PhD'68 (Nuclear Science/Engineering)

As a student in Engineering and a Letterwinner in swimming, I was ‘tapped’ into the Vulcan’s as a Junior ’59-’60. We met weekly in the top room of the Michigan Union Tower. I accepted the task of editing the student directory for the students entering the university in the fall of 1960, for which the Vulcan’s received something like $1,000. Each week, as the Treasurer, I made a motion to adjourn our meeting to the P-Bell in downtown Ann Arbor!

The Union was always an important part of my 11 years as a student at the U-M.

Go Blue!

Reply

Elton Schulz - 1964

You must have come across my name as I was one of the incoming freshmen in the Fall of 1960 enrolled in the School of Engineering. How well I remember the beer and fresh pumpernickel bread at the P-Bell.

Reply

Scott Gerstenberger - 1962, 1966

I still have a tag on my key ring that says “University of Michigan Union 48935 Life Member”. On the other side, it says “Please return to the Michigan Union Ann Arbor Mich”. Over the years, I’ve never lost my keys, but have wondered if I did, would anyone at the Union be able to figure out who “48935” was? I enjoyed spending time in the Union as a student, I can’t remember how I became a “Life Member”.

Reply

Kirk Nims - 1971 1980

I too have a Michigan Union Life Member tag on my keys. It is number 20049. I inherited it from my father who was a Michigan grad. and attended Ann Arbor during the 1930s with my Uncle. My father had been the President of the Ninth District of the UofM Alumni Assn. but is deceased now. They could never find him, but might find me from his records with UofM. I too had wondered about your question.

Reply

Kyle Smith - 1979

I always liked the Union. For me, it was what I wanted U-M to be. Played billiards with my buddies. Enjoyed the quiet. Later, I would bring my high school students to your the campus and the Union was always a bit. Along with the law library.

Reply

Richard Parker - 1960

My memories of the Union precede my college years as I was born and raised in Ann Arbor. As kids we often hung out at the Union. I recall coming to the Union on Sunday nights during the football season where coach Wally Weber showed black and white movies of the previous day’s games in the ball room. Later on while attending Ann Arbor High, at that time located on the east side of State between Washington and Huron, I worked at the Union bowling alley manually setting pins, and later as a busboy at the Union Grill in the basement. Also used the swimming pool on occasion. Later on my friends and I were frequent patrons of the gigantic billiards room where the colorful Joe Kennedy was the longtime attendant. I was saddened that the billiards room did not survive the recent remodeling project. Upon graduation from the Law School I also was given the lifetime membership key ring pendant.

Richard Parker Law 1960

Warren Michigan

Reply

Chris Wu - 1984

My mother frequented the Union as an undergraduate at U of M in the 1930s.She liked to tell the story of a friend in her social group who was frequently paged for a phone call. To protect his beverage, he would always leave a little note on it that said, “I spit in this beer.” One day he came back from his call to find another note on top of his that said, “I spit in it too.”

Reply

Steve Carnevale - 1978

Bravo Tobin! You did it again. You brought to life, as only you can, a unique history from a special time long forgotten except for the magnificent iconic building everyone knows but does not really understand. Buildings are not places. They are time capsules of memories. You transported us back in time to understand again why Michigan is so important in providing an uncommon education for the common man. Like it did for me, the son of a blue-collar automotive factory worker who died young leaving me to rely on social security to pay my tuition. And experience a “men’s club” to help with my “social” education. Thank you Micheeegan for fulfilling your mission for the common man.

Reply

Robert Maddox - 1973 BBS & 1976 MBA

I thoroughly enjoyed learning so much about the Michigan Union.

I was one of the incoming Freshmen in 1969 who found all of the dorms full and was placed temporarily in the common rooms in the basement of South Quad. The University stated that they had no responsibility for providing housing and that we had only a few days before they would evict us. (They had given us no advance warning that the dorms were full.) But after protests by those of us in South Quad and other similar Freshmen in West Quad, the University relented and moved us into the old hotel rooms in the Michigan Union.

I and a roommate shared a suite, including a restroom, with two other students. It was somewhat of a treat roaming the halls of the Union.

As far as I know, we were the only students who had used the Michigan Union as a dorm.

Reply

Timothy Casai - BS73, MArch75

I too was among those displaced and lost freshmen in 1969 who landed in the basement of South Quad. After much protesting and marches to the President’s house, we were housed on the 4th floor of the Michigan Union in rather ancient ‘hotel rooms’. The Union proved to be a very interesting location for the freshman year. Study rooms, pool tables, bowling, and indeed the Michigan Union ballroom proved to be opportunities for the many activities in the Union. We grew to love the building, as well as the student activism that helped to shape the Michigan of the next 50 years!

Reply

Chris Campbell - Rackham '72; Law '75

During my tears in Ann Arbor, 1971-1975, the Union building wasn’t a real student center of activity and i probably entered the building once. It was otherwise as a building and as an organization when my Dad (’39) and his brother (’38, law ’41) were there. After Dad’s death I found his Michigan Union lapel pins and wear them now in jacket lapels–that little block M signifying my connection with a distinguished institution.

Reply

Aric Smith - 1992 DDS, 1997 MS

Thank you for this article and the history lesson about the founding of the Michigan Union. The Union has hosted many special events and prominent speakers over the past century. Although not strictly envisioned by Bob Parker when he wished for a place “…to to bring us all together as Michigan men.”, the Kuenzel Room of the Michigan Union was the site where my wife, Laura, and I were married in 1997. And to us, our union at the Michigan Union has a uniquely special meaning.

Reply

Eugene Gray - BSE 1960, PhD 1968

A most enjoyable read.

Irving Kane Pond married late in life at age 72. In 1929 he married Katherine De Nancrede in Ann Arbor. Announcing his married he is quoted as saying: “It’s the first time I ever did it and I think I ought to be pardoned because of my youth.”

A brief report on the football game with Racine appeared in the Chicago Tribune on May 31, 1879. In conclusion the author writes: “No bones were broken but Torbert was stretched on the turf once. A bucket of water, however, revived him.” First aid was simpler in those days.

Reply

Bob Yecke - Retired employee of University Unions

Great history of the Michigan Union.

In paragraph 12 of the 8th chapter it is stated that the Michigan Union and Michigan League were now part of and organization called the “Michigan Unions.” Actually the organization is called “University Unions” and also includes Pierpont Commons.

Reply

Kim Clarke - U-M Heritage Project

This has been updated. Thank you.

Reply

Jason Burke - 1996

It’s a pity there’s no billiards room anymore, I am guessing because nobody used it? What on earth is an “idea hub”?

Reply

Harvey Beute - 1988

Will always remember watching Edwin Meese and his entourage from the pool hall, get pelted with snowballs as they walked to the Law Quad

Reply

Elaine Wangberg Menchaca, Ph.D. - 1970, 1979

One of my fond memories is of Tom Hayden speaking on the Michigan Union steps circa 1967-8. It was a time of rebellion in the U.S., and UM was very much a part of it. As a woman during that period of time, I never felt a real part of the Union.

Reply

Patricia Strahota Grimes, AIA - 1973

The late 60s and early 70s were a rebellious time indeed in our country, and on campus. During my years at U of M, I went into the Michigan Union building perhaps twice, not understanding its purpose. As a woman, it didn’t mean much to me.

Reply