All in the family

From an early age, Robert Breakey, BGS’ 77/MD ’81, remembers hearing captivating stories about the exploits of his illustrious ancestors, the “Breakey Boys.”

Four successive generations of Breakeys had earned medical degrees from the University of Michigan Medical School over the past century. The contributions, achievements, and valor of the Breakey dynasty were the stuff of family legend.In wartime, Breakey doctors risked injury and death to care for the sick and wounded on the battlefields and front lines of the Civil War, Spanish-American War, and World War I. They also served their country in the military during World War II and the Korean War.

In peacetime, the Breakey Boys ushered the practice and pedagogy of medicine into contemporary times by pioneering new medical specialties and modernizing the curriculum and teaching methods at U-M.

Next in line

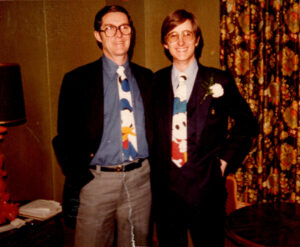

Barry Austin Breakey, BA’ 50/MD’ 53, and son Robert Breakey, BGS’ 77/MD ’81, shared an interest in fashion as well as medicine. (Image courtesy of Robert Breakey.)

“My dad [Barry Austin Breakey, BA’ 50/MD’ 53] enjoyed being a doctor, and he was proud of being number four in the U-M chain of medical graduates,” Breakey recalls. “He hoped that one of his four sons would follow in his footsteps to continue the legacy of our ancestors.”

As a budding biology student at Ann Arbor’s Tappan Intermediate School, Breakey assembled the iconic model kit called “The Invisible Man” to better understand the workings of the human body. That flipped the switch.

“I decided in seventh grade to become a doctor,” he says. “My dad was so proud.”

After graduating from high school, Breakey entered the six-year Integrated Premedical-Medical Program (Inteflex) at the U-M Medical School, which combined undergraduate and medical school education into a single curriculum. When he graduated with his medical degree in 1981, he proudly became the fifth member of the Breakey dynasty of doctors.

“It’s very rare to see five generations of graduates all from the same medical school,” Breakey says. “At the time, we were the only family in the country with that distinction. We were all very proud of our maize-and-blue education.”

Hacksaws on the battlefield

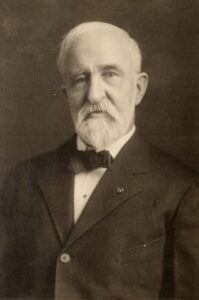

A graduate of U-M’s Department of Medicine and Surgery, William Breakey practiced medicine for several years at Whitmore Lake and served as an assistant surgeon in the Civil War. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Breakey’s great-great-grandfather, William Fleming Breakey, MD 1859, was the family’s patriarch and a larger-than-life figure in the medical field ― and on the battlefield.A graduate of U-M’s Department of Medicine and Surgery, William practiced medicine for several years in Whitmore Lake, Michigan. Then he served as assistant surgeon with the 16th Michigan Volunteer Regiment during the Civil War from 1862-64.

In a September 1862 letter written from Halls Hill, Virginia, to his father-in-law, William described mail call in camp, the second Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), the confused and disorganized retreat of the Union forces to Centreville, and the significant loss of life.

Today, Breakey has a replica of a Civil War-era surgeon’s medical kit, similar to the one his great-great-grandfather used to treat the wounds and diseases of Union soldiers. One prominent medical instrument in the kit is a razor-sharp hacksaw.

“In the early days, antibiotics had not yet been developed, so doctors had to saw off the limbs of patients who had gangrene to save their lives,” Breakey says. “Medical knowledge was sparse, and the U-M Medical School education was only two years long at that time. Doctors did whatever they could with limited resources for people with injuries and illnesses.” The U-M Medical School was founded in 1850.

After suffering a severe wound to his left thigh at the Battle of Gettysburg, William returned to the U-M Medical School, where he became a lecturer and then a professor of dermatology and syphilology. In the 1890s, he also started a clinic to treat patients with dermatological ailments and provide demonstrations for medical students.

William’s clinic established dermatology and syphilology as an independent medical specialty at Michigan and launched the first residency training program of its kind in the United States. Over the ensuing 135 years, this department was destined to become a world-renowned center of excellence for the treatment of melanoma.

During the smallpox epidemic of 1888-89, William served as chairman of the Ann Arbor Board of Health and urged isolation of the sick and disinfection of their bedding to control the spread of the disease.

Casualties of war

Breakey’s great-grandfather, James Fleming Breakey, MD 1894, William’s son, decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and become the second in this line of U-M physicians. Four years after earning his degree, he served in the Spanish-American War.

Military records and a personal wartime journal show that James later served as a U.S. Army Medical Corps captain during World War I. The horrors of wartime casualties were evident in his lengthy letter, dated Dec. 19, 1917, to the chief surgeon for the American Expeditionary Forces unit at American Base Hospital No. 17 in Dijon, Department Cote D’Or, France.

In his letter, James reported on his observations at the British warfront:

James Fleming Breakey, MD 1894, far right, would serve in the Spanish-American War and World War I. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

“Our visit occurred at the most opportune time for observing operations at the front under adverse conditions. We arrived during unusual military activities, some 27,000 casualties having just occurred in the sector, with operations still in continuance…

“We were first detailed to a Casualty Clearing Station to take the place of a team, the surgeon of which has been shot. Here they have been through a most strenuous time, having been running seven operating tables day and night for ten days. One of these was turned over to us, and we had ample opportunity to acquaint ourselves with almost every type of military injury and its surgical treatment. It was, of course, impossible to follow cases up, as practically everything other than laparotomies, bad skull cases, and thigh amputations were marked for immediate evacuation to the Base Hospital…”

After the war, James and his wife, Grace Louise Breakey (nee Collins), LSA/PhB 1896, settled into family life in a house in the Barton Hills area north of Ann Arbor. James joined the medical staff of St. Joseph’s Mercy Hospital and became a well-respected member of the U-M medical community.

Paying with potatoes

Robert Stevens Breakey, MD 1924, was a leader in the emerging specialty of urology. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Breakey was named after his grandfather, Robert Stevens Breakey, MD 1924, and still cherishes the gold-plated cystoscope presented by the American Urological Association to the elder Breakey in 1939 for his pioneering work in the emerging specialty of urology.

Robert registered for military service at age 19; in 1917, he accompanied his father to France in WWI. After medical school, he practiced urology in Lansing and raised his family in Spartan country while remaining true blue to his alma mater.

Accounting ledgers from Robert’s medical practice show he charged $2 for an office visit. During the Great Depression, he gladly accepted a sack of potatoes or a couple of plump chickens in lieu of hard cash since there was no such thing as medical insurance at the time.

In 1933, Robert bought 40 acres of land on the north branch of the Au Sable River, which became a restful retreat for his family. Breakey has fond memories of sitting around the campfire at Flashlight Bend with his grandfather and grandmother, his parents, and his three younger brothers, enjoying the Michigan wilderness.“My grandpa was an avid stamp collector, specializing in the 1902-03 series, and a nationally known philatelist who traveled to many national shows in his spare time,” Breakey recalls.

In the 1970s, his grandfather sold his stamp collection for a hefty sum. He transferred the money to a trust fund to cover his eight grandchildren’s college tuition expenses.

Refocusing on primary care

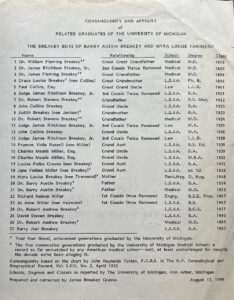

Related Breakey graduates of the University of Michigan. (Click image to enlarge. Courtesy of Robert Breakey.)

Breakey’s father, Barry, grew up in Lansing, but he returned to Ann Arbor to earn his medical degree at Michigan in 1953. The Korean War was still raging, so as an intern, he was swept up in the “doctor’s draft.” Barry elected to join the U.S. Navy as a flight surgeon and was stationed aboard a U.S. Navy destroyer off the coast of Hawaii.

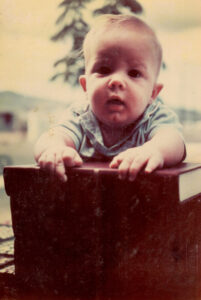

“I was born in Honolulu in 1955, before Hawaii was a state, and we lived there until I was 15 months old,” says Breakey, the family’s firstborn of four sons.

In 1957, Barry and his wife Myra, BS ’48 Dental Hygiene, moved their growing family back to Ann Arbor. Barry completed his urology residency at U-M and then practiced as a urologist at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital for 40 years.

“My dad was a prolific artist and a Life Master Bridge player who competed in national tournaments,” says Breakey. “He was always very engaging and supportive of my career in medicine.”

They start early in the Breakey family. In 1957, baby Robert prepares to crack into some medical textbooks. (Image courtesy of Robert Breakey.)

When Breakey graduated from the U-M Medical School nearly 30 years later, however, he did not follow in the footsteps of his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather who became specialists in urology, surgery, and dermatology.

Instead, he chose to specialize in a modern-day field, intent on creating a new wave of innovation with his board certifications in Family Medicine and Lifestyle Medicine. This brought him full circle to the more generalist approach to primary care medicine used by doctors in his great-great-grandfather’s time.

Breakey is guided by this prophetic quote from a genius contemporary of his distant physician ancestors:

“The doctor of the future will give no medication, but will interest his patients in the care of the human frame, diet and in the cause and prevention of disease.” –– Thomas Edison, 1903

Legacy of lifestyle medicine

This replica of a Civil War-era medical kit is similar to one that William Breakey might have used in the field. (Image courtesy of Robert Breakey.)

“My great-grandfather, grandpa, and dad were part of several generations of medical innovators who were intent on defining and managing as many diseases as possible,” Breakey says. “And here we are in 2025 with a very high-cost healthcare system that is focused on managing a growing epidemic of chronic diseases, with little attention paid to addressing the root causes of these diseases.”

The incidence of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and several cancers has risen sharply in the U.S. since 1903, as well as worldwide. This trend has proven costly to individuals and society, both financially and personally as it relates to avoidable pain and suffering.

Much of this rise has been attributed to unhealthy diet, inadequate sleep, lack of exercise, high stress, and poor social connectedness.

Robert Breakey and his granddaughter, Emilia, review the touch points of Lifestyle Medicine. (Image courtesy of Robert Breakey.)

“In lifestyle medicine, we recognize the body’s innate healing abilities,” Breakey says. “When you nourish, support, and enhance a person’s internal healing powers, great things can happen ― ranging from the reversal of type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, or obesity to the achievement of true vitality and positive wellness rather than just the absence of disease.”

Breakey estimates that more than 80% of the diseases he sees in his lifestyle family medicine practice in Ann Arbor are largely preventable. Many also are commonly reversible by inspiring positive lifestyle behaviors, such as exercising, eating a whole-food, plant-based diet, ceasing tobacco use, and ensuring good-quality sleep.

“In lifestyle medicine, we focus on addressing the root cause of chronic diseases and inspire people to adopt a healthy lifestyle to prevent and, where possible, reverse these conditions and restore their health and vitality,” says Breakey, a nationally known leader in lifestyle medicine.

“On behalf of my maize-and-blue dynasty of healers, supporting this paradigm shift to a truly health-promoting medical care system will be my legacy,” he says.

(Lead image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library. James Fleming Breakey, MD 1894, is pictured, far right.)

Heather Mullett - 1963 Law

Long after I graduated from Law School, I learned that my great grandfather, John Henry Doughty, had received his medical degree at Michigan 100 years earlier and gone directly to serve with the Union Army as a surgeon. I had two great aunts, (the one I knew was his daughter, Phebe VanVlack Doughty) who later studied medicine at Michigan. JHD wrote an account of his medical education and experience (at the time of a reunion?) 40 years later. He did not live long thereafter, but it was preserved and I have shared it with many, especially my grandchildren, as an example of how hard he worked to achieve his education.

Reply

Doug Wagner - 1984 LSA

What an amazing chronology of a Wolverine family’s service in the medical field. Kudos to the Breakey family. May that fine and admirable tradition continue for many generations to come, starting with Emilia! Thanks Dr. Bob for your Eight Keys to Health and Success. May we all grasp that wisdom and sail on into a healthy and enjoyable life!

Reply

Mike Jefferson - 1980

Lovely historical narrative, though the readers were left hanging as to whether Bob Breakey’s children (and/or grandchildren) are pursuing careers in medicine?

Reply