Wonders to be seen

Van Allsburg returned to U-M in 2012 to receive an honorary doctorate. (Image: Scott C. Soderberg, Michigan Photography.)

When author/illustrator Chris Van Allsburg, BFA ’72, set his freshman foot on the Michigan campus, the sun had barely set on the Summer of Love. Imagine this accidental art student dropping right into the mythic Ann Arbor of pop-culture lore, the one you read about in the yellowed archives of The Michigan Daily. It was a colorful, passionate, and youth-oriented universe unlike anything he’d experienced growing up in his small town outside Grand Rapids.

“I was in art school, so I was around a bunch of musicians and artists, which may have intensified the psychedelia that was defining the culture at that point,” says the author of such award-winning bestsellers as Jumanji (Houghton Miflin, 1981) and The Polar Express (Houghton Miflin, 1985). “It was an exciting and, sometimes, frightening time.”

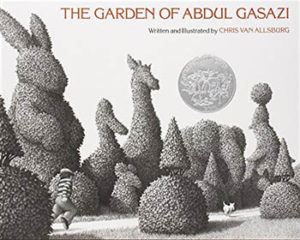

The same could be said for Van Allsburg’s books, which meld fantastical narratives with “exciting and, sometimes, frightening” illustrations that defy reality: a rhino wreaking havoc in the living room or a train chugging down a quiet suburban street. Since publishing his debut children’s book, The Garden of Abdul Gasazi (Houghton Miflin Harcourt, 1979), Van Allsburg has gravitated toward the alternate universe and the unanswered question. But for someone with such wild ideas, the artist is firmly grounded in reality.

“I don’t think anybody who knows me would describe me as jolly and whimsical,” he says. “I’m a bit more of a pessimist and a skeptic. The things I write are not elaborate enough to be a substitute reality, but they do represent a brief escape for me, just because they absorb my concentration and help me disengage from the reality that I am obliged to live in.”

The holiday release of the film Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle (Sony, 2017) inspired the artist to return to Michigan in December, where he supported fundraisers at screenings in Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids. Proceeds went to Jo Elyn Nyman Anchors Programs for Children at Hospice of Michigan and Arbor Hospice.

Michigan Today took the opportunity to ask Van Allsburg about his creative process as a sculptor, illustrator, and children’s author. Here’s what he said:

THE ONE BOOK he admits to reading multiple times? Harold and the Purple Crayon. “I could read three books a day, live a long life, and not need to go out and buy another book,” the writer says of his extensive home library.

HE STARTS most narratives with the simple prompt “What if?” and goes from there. “It’s like that time in our lives when we’re young, and our parents describe something preposterous on its face – a guy in a red suit flying around the world on a sleigh. It’s ridiculous, but for the period of your life during which you believe that’s true, the world is a much more miraculous place.”

IT’S POSSIBLE for him to time travel through his work. “It is not hard for me to recall where my head was at when I was 8 or 9.”

COGNITIVE DISSONANCE sparks his creativity because it’s a surprise. Jumanji, anyone? “I like seeing things juxtaposed that don’t belong in the same picture.”

THE BEST part of his latest project? “The fact that I haven’t worked on it long enough to realize it’s not going to be perfect. In my experience making art, by the time you actually get done making the physical thing, it’s never quite as great as you imagined it would be when you began working on it.”

AS AN ILLUSTRATOR/AUTHOR Van Allsburg often leads with a picture. “I grew up in a visual age where you’re exposed to film, TV, and all sorts of things on a screen. I think [modern-day writers] have a stronger drive to describe the setting of a story because they always see stories set in a particular environment. It’s possible a 19th-century writer might be more concerned about character and dialogue and less concerned with setting.”

HIS FAVORITE TV show as a kid featured a “pudgy, jolly actor” named Andy Devine, who surrounded himself with puppets and other “interesting” characters, one of which was a frog who appeared on screen as the host commanded: “Plunk your magic twanger, Froggy!” As Van Allsburg says, “It’s just an ephemeral vapor of a memory, and I don’t know why, but it has stayed with me my whole life.”

A HAPPENING is not a story, Van Allsburg says. “There are a fair number of children’s books that could best be described as a series of events. I want my characters to experience a series of events that changes them – that makes the character think differently and makes you think differently. I mean, that’s called ‘a plot,’ and a lot of children’s books don’t have a plot.”

THE INNER CRITIC is his friend. “I’ve sometimes been described as a perfectionist. But I prefer to describe myself as someone who is very observant and has very high standards. I’m only concerned with the things that are wrong. My life as an artist has always been spending the day identifying what’s wrong. You don’t need to identify what’s right, because if it’s right, it’s done.”

HE LUCKED OUT and was accepted into the now-Stamps School of Art & Design before a portfolio was required. He had no idea what art school entailed. “I went in as a complete naïf,” he says. “My drawing skills were ‘undeveloped’ to say the least.” But his penchant for making models as a kid translated to a penchant for 3-d art and sculpture as an adult. Meanwhile, his need to draw whatever he planned to sculpt helped him hone his skill as an illustrator.

THE FIVE-YEAR PLAN in college worked well for Van Allsburg, who purposely neglected to fulfill graduation requirements so he could hang around an extra year to make use of the University’s wood shop, bronze foundry, and other art resources and facilities. “Coming back to claim my last six credits in art history was a great deal.”

COMMANDER CODY and his Lost Planet Airmen infiltrated Van Allsburg’s college experience. One member of the band was a graduate student instructor. Meanwhile, a classmate played saxophone with the band Galactic Twisted Queens of Soul (if memory serves). Friends dragged Van Allsburg to see proto-punk rockers the MC5, where it’s likely someone in the audience yelled, “Plunk your magic twanger, Froggy!”

CHILDREN’S HOSPICE is a cause Van Allsburg and his wife have long supported. Various premieres of his books-turned-movies — Jumanji, Polar Express, and Zathura — have doubled as fundraisers to support children’s hospitals and hospice in Rhode Island (where he used to live) and Michigan (where he grew up). The December 2017 premiere screenings of Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle in Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids raised funds for Jo Elyn Nyman Anchors Programs for Children at Hospice of Michigan and Arbor Hospice. For someone who favors cognitive dissonance, the thought of children in hospice is a devastating concept. So even though Van Allsburg was not associated with the film production, he knew he could make a difference by supporting the events, meeting fans, and signing books.

“It’s a great way to raise money for a cause that is not only worthy, but also poignant,” he says.

Peter Rogan - 1977, LSA

Imagination can save us all, if only we let it

Reply

Rosemary Buchmann - BFA 1988

As an art student at UM in the early 80s, I was exposed to Van Allsburg’s stories and illustrations. I was/am rather bothered by the movie industry turning his stories, (and so many others) into motion pictures. It feel it ruins them. Why is it that the movie industry thinks they can take a short children’s story and turn it into a lengthy film? They take a lot of ridiculous artistic license adding more than there is to the story leaving youngsters no opportunity to imagine for themselves.

There is a very big difference from the original, older, short cartoons such as Charlie Brown’s Christmas or the Grinch. These were 30 minutes long and did not take liberties with the story. I flatly refuse to watch any of the new film adaptations of wonderful children’s short classic stories anymore. I really wish filmmakers would cease making them.

Reply

Bruce Skinner - Staff

I can understand Rosemary’s concern about how a motion picture can differ greatly from the book it’s based on. One way we can deal with that is to get kids to read the book and see the differences. I remember when my now teenage daughter was in elementary school. She and her friend were watching the video for the movie The Vampire’s Assistant. They had both read the series. Throughout the movie, they kept commenting on the differences. When the movie was over, they said they liked the books much better. Maybe this is one way we can get kids get interested in books as opposed to just watching the movie.

Reply