… and the role a film critic played

Sixty years ago the U.S. Supreme Court resolved a test-case challenge to legal censorship of motion pictures in the United States. The drama leading up to the decision concluded a lengthy journey through the courts lasting a year and a half. Involved in the fray was a fascinating cast of characters: film personalities, politicians, religious officials, and one outspoken film critic.

Back story

A century ago, censorship of American movies was accelerating at a breakneck pace. Almost from the first film showings in nickelodeons, municipal and state censorship boards sprang up to oversee the “moral fitness” of motion pictures. Chicago officials created the first city board in 1907; Pennsylvania the first state board in 1911. By 1922 more than 30 American states had initiated legislation resulting in frustrating content restraints that varied widely from one geographic location to the next.

Underwriting the expansive censorship was the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1915 decision in the case of Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio (236 U.S. 230). The decision held that “the exhibition of motion pictures is a business pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit, like other spectacles, not to be regarded, nor intended to be regarded … as part of the press of the country or as organs of public opinion.”

This decision would remain unchallenged for decades. Its stultifying impact on free expression in film would be further exacerbated by the introduction of the Hays Code in 1930 by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). Self-regulated, the code cited several specific taboos, among them “illicit sex, illegal drug use, methods of crime, miscegenation, and pointed profanity.” More generally, producers and writers were cautioned to show respect for “religion, national feelings, and law and justice.” In a nutshell the MPPDA code required that sin be punished and virtue rewarded.

Those who defied the rules were fined and denied a Code Seal of Approval. Those who obeyed often were forced to write and produce “morally compensating” narratives in which good triumphed over evil. A case in point: At the end of the screen adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s The Letter (1940), the murderous villain is abruptly stabbed to death by a servant. In the novel the character remains alive at book’s end, condemned to a hellish life of guilt and remorse. By resorting to the “payback” strategy, films of the ’30s and ’40s often appeared dishonest, hypocritical, and lacking in moral sting when dealing with complex human relations.

The plot thickens

Following World War II, social and political themes increasingly appeared in Hollywood films. The Lost Weekend (1945) offered a stark treatment of alcoholism. Crossfire (1947) and The Gentleman’s Agreement (1949) exposed anti-Semitism in American life. Intruder in the Dust (1949) dealt with racial prejudice, and All the King’s Men (1949), adapted from Robert Penn Warren’s sprawling novel, was a dramatic treatise on political greed and corruption. Each film presented serious, important ideas. Yet producers continued to work without free-speech protections.

Then, in 1948, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas opened the door to debate when he wrote the majority opinion in the United States v. Paramount anti-monopoly case: “We have no doubt that moving pictures, like newspapers and radio, are included in the press whose freedom is guaranteed by the First Amendment.” The dictum seemed to hint that a test case was needed.

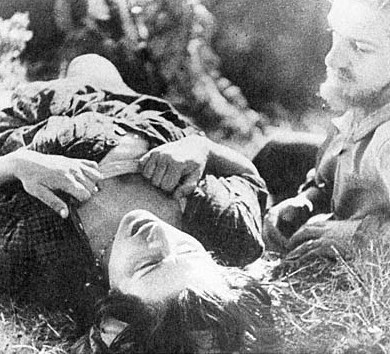

Ironically the test-case film would not come from Hollywood. Rather, it was a 1948 movie from Italy titled The Miracle. Director Roberto Rossellini collaborated with 26-year-old writer Federico Fellini on the provocative, 47-minute film, in which Fellini starred alongside the magnetic Anna Magnani.

Fellini’s story—taken from a childhood memory of a summer visit to his grandmother’s small Italian village in Romagna—is that of a demented goat herder, Nanni, whose confused religious fervor leads her to believe she has conceived immaculately after an encounter in the mountains with a man she mistakes for St. Joseph. Spurned by the local villagers, Nanni must deliver her child alone in an overhang of a Catholic church.

The legal battle begins

The challenge to the legality of statutory censorship began in December 1950 when The Miracle opened at the Paris Theater in New York City. The film had been brought to the United States by Joseph Burstyn, a Polish-born importer of foreign and independent movies.

Many critics saw The Miracle as an allegorical statement about social and institutional insensitivity to basic human needs in poverty-stricken, post-WWII Italy. In his two great post-war films, Rome: Open City (1945) and Paisan (1946), Rossellini’s neo-realistic narratives seemed to convey a wariness of organized religion and the sincerity of the church regarding humanitarian concerns—a theme carried forth in The Miracle.

Protests

Immediately after its opening, the Catholic Veterans of New York took to the streets in protest, calling the film “sacrilegious” and a “mockery” of the church’s belief in the miracle of the virgin birth.

One placard read: “The Miracle is an affront to every woman and her mother.” On Jan. 7, 1951, Francis Cardinal Spellman, archbishop of New York, ordered that his denouncement of The Miracle and Rossellini be read at every Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral that day. Spellman described the film as “revolting, blasphemous, and sacrilegious” and said “the picture should very properly be retitled ‘a woman further defamed by Roberto Rossellini.'”

Spellman was referring to the scandal that erupted in 1949 when Ingrid Bergman conceived a child by Rossellini while filming Stromboli in Sicily. Bergman went into exile in Italy, leaving behind in the U.S. her husband, Peter Lindstrom, and young daughter, Pia. Bergman and Rossellini (who also was married at the time) would be denounced on the floor of the House of Representatives and in the U.S. Senate for their behavior. Sen. Edwin Johnson of Colorado maintained, “We must protect ourselves from such scourges.”

In February 1951 the New York State Board of Regents declared The Miracle “sacrilegious” and revoked the film’s exhibition license, sending the legal battle (Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson) into the appellate courts and eventually to the Supreme Court.

A religious showdown

To a significant extent the legal battle represented a showdown with the Catholic Church. The Hays Code had been written by two Catholics, Martin Quigley, a motion picture trade magazine publisher, and Daniel Lord, a Catholic priest who taught drama at St. Louis University. Joseph I. Breen, a prominent newsman and a Catholic, oversaw the Production Code Administration. Enforcement of the Hays Code had taken on new urgency with the creation of the Catholic Legion of Decency in 1933—annually American Catholics were required to pledge to abide by the legion’s own decency ratings of films.Cardinal Spellman opened his denunciation of The Miracle by reminding the archdiocese of the Legion of Decency pledge and each parishioner’s duty to avoid “indecent and immoral films, and to unite with those who protest against them.”

Not only did The Miracle case signal a showdown against long-standing and powerful church forces, the legal battle also played out at a most uncertain political time in American history. After the House UnAmerican Activities Committee’s (HUAC) visits to Hollywood in 1947 and 1951-52 (in search of film industry “Reds”), writers and producers began backing away from controversial themes. After the HUAC inquiry Jack Warner announced that Warner Bros. would make no more pictures with “little man” themes. In part because of the uncertain political times, a nervous Hollywood also avoided The Miracle controversy. No one spoke up on behalf of the test case.

Enter Bosley Crowther

New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther, more than any other public figure, acted in support of Joseph Burstyn’s legal battle as it went through the courts. In his columns and in national news magazines, Crowther kept the importance of the case before the public. He wrote time and again of the need for reversing “the old stigma on movies as cheap entertainment.” He spoke forcefully of the effect a reversal would have in stimulating film artists to reach out for dramatic material of vitality and importance to life—uninhibited by censorship laws. He also wrote with dismay that no voices from Hollywood had been raised on behalf of the Miracle case.

In a unanimous decision (343 U.S. 495) announced on May 26, 1952, the Supreme Court declared that The Miracle was not censorable because of a single group’s interpretation of sacrilege. Justice Felix Frankfurter, in his concurring opinion, wrote: “The fact that motion pictures are a large-scale business conducted for private profit does not prevent them from being a form of expression whose liberty is safeguarded by the First Amendment.”

Frankfurter cited Crowther’s writings twice, including his synopsis of The Miracle‘s plot, his interpretation of its various meanings, and its potential for controversy. Anticipating the outcome, Crowther was in Hollywood when the decision came down. In the article he sent back to The New York Times he summarized the import of the decision as such:

“It is significant that the Miracle case was fought by an independent importer of foreign pictures, Joseph Burstyn, without the support of the organized film industry, and that its outcome reasserts the freedom of thought and expression which other elements in the industry seem ready to resign in the face of dubious pressures and dark depressing fears. The Supreme Court has reminded the filmmakers that they live in a society of free men.”

Although the Miracle case was only the first of a series of court tests against state and municipal censorship, it began a progressive movement in the courts toward upholding free speech rights of motion pictures. To the end of his career in 1968, Bosley Crowther would continue to use the critic’s pen to reveal the fallacies of statutory censorship and the anomalies and hypocrisies of self-regulation.

Mick McQuaid - 1986

Interesting article!

The opening of the “Back Story” could benefit from earlier dates. The wonderful short film “100 Years at the Movies” asserts that commercial film exhibition began in April, 1894, over a decade before the nickolodeon. Censorship began that same year with Carmencita, a 21-second film made at Edison’s studio earlier that year and banned in various venues by public officials that summer, more than a dozen years before the Chicago censorship board mentioned in the article.

Kinetoscopes were big business by 1895 and numerous sexually controversial titles were censored that year.

Reply

ken smith - 1977

Thank you for such an informative and interesting article.

Reply