“We are just a family of professional actors.”—Vanessa Redgrave

Among the new British films I caught earlier this year in London was a low-budget independent feature starring Terence Stamp and Vanessa Redgrave, two of England’s most revered and adventuresome actors. The film, Song for Marion, was written and directed by Paul Andrew Williams. Like earlier British films of its type, e.g. Calendar Girls (2003), The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2012), and Quartet (2012), Williams’ story centers on aging protagonists whose lives progress toward a revitalization of spirit.

In this case, we follow Marion (Redgrave) and Arthur (Stamp), a married couple in their 70s. Marion is terminally ill with cancer, but continues to sing in a senior citizens’ community chorus. She begs her grumpy, distant husband to join the group—which is led by a spirited, nontraditional young conductor, Elizabeth (Gemma Arterton). Arthur resists until Marion dies, and Song for Marion moves toward its very sentimental resolution.

Although this little film doesn’t match its forerunners in quality, Stamp and Redgrave are powerful presences on the screen, and Redgrave is profoundly memorable when she sings Cyndi Lauper’s “True Colors.” Now 76, Redgrave has made more than 80 films since her first appearance in Behind The Mask in 1958.

Cast of characters

Not long after seeing Song for Marion I was browsing in the media section of a Waterstone’s bookshop and happened upon The House of Redgrave: The Secret Lives of a Theatrical Dynasty by Tim Adler. Essential players who comprise this “theatrical dynasty” include repertory actors Roy Redgrave (b. 1873) and Daisy Scudamore (b. 1884). Their son Michael Redgrave was father to Vanessa, Corin, and Lynn Redgrave. Vanessa was married for five years to Tony Richardson; together they had two daughters, Natasha and Joely Richardson. There are other spouses, children, and grandchildren, but the above lineage constitutes the unauthorized biography’s key players.

Not long after seeing Song for Marion I was browsing in the media section of a Waterstone’s bookshop and happened upon The House of Redgrave: The Secret Lives of a Theatrical Dynasty by Tim Adler. Essential players who comprise this “theatrical dynasty” include repertory actors Roy Redgrave (b. 1873) and Daisy Scudamore (b. 1884). Their son Michael Redgrave was father to Vanessa, Corin, and Lynn Redgrave. Vanessa was married for five years to Tony Richardson; together they had two daughters, Natasha and Joely Richardson. There are other spouses, children, and grandchildren, but the above lineage constitutes the unauthorized biography’s key players.

The plot

True, the book chronicles the now-not-so-secret accounts of marital infidelities, diverse sexual proclivities, and activist causes often bordering on the fanatical. But these have all been addressed in earlier family autobiographies and other Redgrave biographies. What is most interesting and informative about Adler’s work is its cultural significance for British film and theater history, most notably the revolutionary stylistic and thematic transitions that occurred in the 1950s and ’60s.

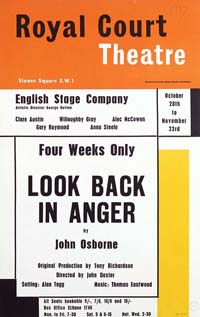

The revolution had its beginnings at the Royal Court Theatre on Sloane Square, spearheaded by the uniquely dynamic vision of Tony Richardson. He would marry Vanessa Redgrave in 1962. In 1955 Richardson directed the third production at the Royal Court, John Osborne’s Look Back In Anger which was submitted after an advertisement for new plays appeared in The Stage newspaper. The play’s protagonist, an invective anti-establishment man named Jimmy Porter, initiated what would be called the “angry young man” movement, and its homely lower-class stage setting inspired the stylistic phrase “kitchen-sink realism.”

The revolution had its beginnings at the Royal Court Theatre on Sloane Square, spearheaded by the uniquely dynamic vision of Tony Richardson. He would marry Vanessa Redgrave in 1962. In 1955 Richardson directed the third production at the Royal Court, John Osborne’s Look Back In Anger which was submitted after an advertisement for new plays appeared in The Stage newspaper. The play’s protagonist, an invective anti-establishment man named Jimmy Porter, initiated what would be called the “angry young man” movement, and its homely lower-class stage setting inspired the stylistic phrase “kitchen-sink realism.”

The play, which opened on May 8, 1956, has long been cited as a monumental event in British theater because of its turn away from traditional “elite” stage fare. Adler recalls critic Kenneth Tynan’s comment that he could “scarcely remember the theatrical landscape as it was before (the Royal Court) called in John Osborne, the Fulham flamethrower, to scald us with his rhetoric.”

Initially, Adler notes, audiences and critics alike didn’t know what to make of Look Back In Anger. Some prominent first-nighters walked out and various reviewers called the drama “self-pitying snivel,” “the most putrid bosh.” Another said it made him “feel numb.” Sunday newspaper critics, however, were more positive—even offering two raves—and one government official joined in to praise the play for its “great intuitive understanding of what people are feeling … people too decent to express themselves aloud.” Audience numbers increased and the play held its ground.

The Plot thickens

In many ways Tony Richardson becomes the central figure in The House of Redgrave—the family member to whom all the others would remain intensely connected until his death in 1991—and beyond. “The more I found out about Tony,” writes Adler, “the more I realized you couldn’t understand him without describing his relations with the rest of the family, who circle each other like a solar system.”

Vanessa became an inimitable theater and film actress in works often directed by her husband, even after their divorce in 1967. Daughters Natasha and Joely Richardson, born in 1963 and 1965, would establish their own impressive professional acting careers, also often working with their father. Richardson’s importance broadened in 1958 with the founding of Woodfall Film Productions, established for the purpose of making a film version of Look Back In Anger. Richardson would direct as he would many of Woodfall’s earliest films. Playwright John Osborne joined as a co-founder.

As with his presence at the Royal Court Theatre, Tony Richardson and Woodfall Films would change the landscape of British cinema. First there was Look Back In Anger (1959) with the remarkable Richard Burton as Jimmy Porter. This was followed by the screen adaptation of John Osborne’s play The Entertainer (1960), a film set in England’s dwindling resort music halls with its protagonist Archie Rice, an aging variety show performer caught up in a dying part of British cultural life. Laurence Olivier portrayed Archie, later saying he hoped it would be the role for which he was best remembered. To see this film and consider it alongside his Shakespearean film portrayals provides incontrovertible evidence of Olivier’s powerful acting range and skills.

Woodfall Films served as fertile ground for a wave of realistic human dramas about working-class people. Other important Woodfall films included screen adaptations of Alan Sillitoe’s gritty, Nottingham-based fiction: Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1961) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962). Each was about a solitary young man, a free-wheeling rabble-rouser in the former and a rebellious juvenile delinquent in the latter. Tony Richardson’s father-in-law Michael Redgrave portrayed the detention-center governor in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner.

Dramatic tension

The House of Redgrave traces through the next three decades of Tony Richardson’s life and career, which includes the resounding international critical and popular success of Tom Jones (1963), adapted from Henry Fielding’s picaresque novel. Richardson’s direction was rousing, often erotic, and cinematically innovative. The film earned 10 Oscar nominations, winning four, including Best Picture and Best Director for Richardson. Adler writes how this “British invasion” didn’t set well with a lot of Hollywood hard-liners.

Adler’s book also offers a thorough accounting of the theater and screen work of all the Redgrave clan, from patriarch Michael Redgrave to youngest granddaughters Jemma Redgrave and Joely Richardson. Adler provides vivid critiques of Vanessa’s film work in Isadora (1968) and Julia (1977) for which she won a controversial Best Actress Oscar, upsetting many in attendance because of political comments made in her acceptance speech; of Corin’s early acting career; of Lynn’s brave breakthrough film role in Georgy Girl (1966); of Natasha Richardson’s Best Actress Tony Award for Cabaret (1998); and of Joely Richardson’s huge success in the CBS-TV series “Nip/Tuck” (2003-10).

Adler’s critiques of the Redgrave family’s stage and screen work are often accompanied by well-chosen, incisive quotes by reviewers and fellow actors, raising the discussion to a level above any charges of show-biz gossip. The extensive coverage of Vanessa and Corin’s ongoing social and political activism is blended in as factual asides to the siblings’ very interesting public lives. As in any family history House of Redgrave is an altogether human one: divorces, heartbreak, infidelities, illness, death. All are discussed without sensational tailoring.

On a final note Adler refers to the Redgrave family as a theatrical dynasty. Vanessa, the sole survivor of Michael Redgrave’s three children, rejects the dynasty label. She argues: “A dynasty implies power, while the Redgraves are just a family of professional actors. The only power they have is to try and do the best work they can.”

In Adler’s lengthy counter-argument he writes: “The Redgrave power springs from the spontaneity Michael instilled in his three children when they were learning the craft. At best there’s seemingly no distance between them, the writer’s ideas, and the audience. Somehow a good Redgrave performance uses all three. It’s as if what they’re saying really has only just occurred to them. Corin or Natasha could communicate a character’s entire history in one evanescent moment. It’s a rare gift and why the Redgraves are so highly regarded.” Those powerful qualities, seemingly passed so easily from one generation to the next, Adler feels, signal a theatrical dynasty. I would agree.

Anonymous

Dr. Beaver: Please send me your email address so I can tell you how important you are for the way my life has gone. Harry Epstein (class of ’71 and M.A. in ’72)

Reply

Walt Naumer

I read this article with great interest. While I have enjoyed Vanessa Redgrave films from time to time (if not her politics) I did not realize there was a dynasty of such artistic accomplishments. But then with my academic vita (business, law) I probably am more barbarian than Renaissance Man. Thanks to you, I now have a list of titles for Netflix selection.

Reply