In 1911 the University enlisted a young woman named Myrtle White to raise money to build dormitories for women in Ann Arbor. (There were no dormitories for either sex in that era, but the rising number of female students had led to a common view that private rooming houses could no longer meet the need.)

Myrtle White had only recently graduated from U-M. Yet despite her age and inexperience as a fundraiser, she made appointments with wealthy alumni in New York and went to ask for help.

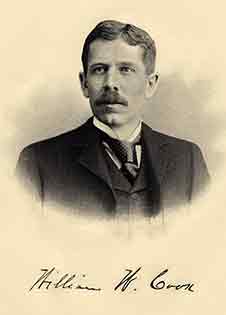

In the heart of Wall Street, she found herself looking across a spacious desk at William Wilson Cook, a U-M law graduate of 1882, a major force in American corporate law, and a very wealthy man. (He was chief counsel to the Mackay telegraph and cable companies, Western Union’s main competitor.) Cook was divorced—unusual for a man of his station in that era—irascible, opinionated, and inclined to be generous to his alma mater.

He was immediately interested in Miss White’s proposal.

“Have your president call on me,” he said.

So it was that President Harry Burns Hutchins soon secured Cook’s promise to help pay for the construction of a women’s dormitory. Before long Cook would pay for the whole thing, plus furnishings.

The Martha Cook Building, named for Cook’s mother, was not the first women’s dorm at Michigan. The Helen Newberry Residence enjoys that distinction by a thin margin.

But perhaps more than any building at U-M—even more than the Law Quadrangle, Cook’s far larger gift to the University—Martha Cook bears the stamp of its benefactor. He chose the architect (York and Sawyer of New York, who had designed Cook’s own home and would go on to design the Law Quadrangle); gave many of the furnishings; and oversaw the design from afar.

To the knowledgeable visitor who strolls through Martha Cook’s public rooms and corridors, it is as if Cook’s ghost walks alongside, pointing to things he held dear and symbols of things he believed.

Especially remarkable are representations of women—the gender in general and several women in particular.

“Home, the Nation’s Safety”

The fireplace inscription reads: “Home, The Nation’s Safety.” Image courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library.

“The purpose of that building,” Cook wrote to President Hutchins, “was and is to raise the standards of all of the young women in the University by selecting the best examples and organizing them as a unit.”

He believed in women’s education. But his standards for women belonged to an era that was passing even as Martha Cook was being built. They were Victorian standards that cherished the woman-as-mother, the foundation of morality in a stable society.

“America is a woman’s country,” Cook once wrote. “Women control the social life, the religious life, the artistic life, the encouragement of literature, the household expenditures, the customs and manners. If woman becomes mannish, her influence over man will decline and manners, customs, and morals will deteriorate … And then there are the children. At a tender age they imbibe the principles and teaching of their mother. If they are reared to revere their country, and uphold its austere institutions, the future is safe.”

Thus the role of the Martha Cook Building: In Cook’s mind it was to be a place of domestic beauty where young women of the University—including “poor girls,” Cook was specific about that—would learn the domestic virtues and thus help to preserve all that Cook valued in the vanishing small-town America of his boyhood.

So when Martha Cook’s designers put a space for an inscription on the fireplace in the dining room and asked Cook what words to choose, he replied: “As I pass along Wall Street and hear the strident voices of women suffragettes declaiming in open automobiles, I feel that we are drifting from our ancient moorings. Hence, a ‘recall’ inscription on the Ann Arbor building might be appropriate, such as ‘Home, the Nation’s Safety.’”

Portia at the door

Over the front door on South University, the architects placed a niche for a statue. But of whom? Cook rejected classical and biblical figures. “You will notice they are all angels or saints,” he remarked, “and not a lawyer or sinner among them.”

Then he hit on the idea of Portia, the heroine of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.

Why did she appeal to Cook?

He admired well-educated women and believed law and lawyers to be the foundations of American society; he also nurtured a variety of anti-Semitic views common to WASPs of his generation. Thus his enthusiasm for Portia. As the brilliant apprentice to a lawyer, she outwits the hateful moneylender Shylock. She was “Shakespeare’s greatest lawyer,” he said, “who … brought to book the bloodthirsty Jew—a full-throated woman of vivacity, poise, and feminine charm.”

So it was that anti-Semitism played an ignominious role in a campus landmark. (Cook’s Portia, incidentally, was sculpted by Attilo and Furio Piccerilli, who, with their four brothers, carried out Daniel Chester French’s design for the statue of Abraham Lincoln that sits in Washington’s Lincoln Memorial.)

Venus in the corridor

At the far end of the main corridor of the first floor, the visitor glimpses an exact replica of the armless Venus de Milo. It was found in Genoa, Italy, and shipped across the Atlantic in the spring of 1917, just as the U.S. was entering the First World War. For a time the ship was feared lost, Venus with it; then both turned up safely in port and Venus was hauled to Ann Arbor.

For the niche over the front entrance, Cook had rejected classical models. But he was glad to have this particular goddess. “The statue of Venus knows no age, no nationality, and no locality,” he remarked. “It is cosmopolitan, belonging to all ages, all nations, and all localities. Venus, you know, according to the Greeks was born of the foam of the wave, and hence was a child of nature.”

Mrs. Cook in the Red Room

Martha Cook portrait, from the George Swain collection, courtesy of the U-M Bentley Historical Library.

Cook venerated his mother, Martha Wolford Cook (1828-1909), the daughter of a Dutch family in upstate New York. As the wife of John Potter Cook—a descendant of Plymouth Colony pioneers, a founder of Hillsdale, Mich., and a well-to-do businessman and banker—she raised nine children; William was the third. Beyond that, not much was known of her, and when an artist was commissioned to paint her portrait for the dormitory, Cook had only a single daguerreotype of his mother to lend as a model.

The artist was Henri Caro-Delvaille, a young French Impressionist painter who was in the U.S. recuperating from war wounds. In his portrait of Mrs. Cook, he said, “I have tried to portray an epoch in which the mother was queen in her home … respected for the simplicity of her manners and the greatness of her virtues.”

The portrait hangs in the Red Room, which was built to replicate the library of a 17th-century English manor house. On another wall hangs a Flemish tapestry. It showed “a hunting scene,” William Cook remarked, “and I don’t know whether such a scene would fit in with that building unless they call it ‘Uncle William hunting duck in the Seventeenth Century.’ I’m not sure whether it is a duck or a goose. Judging from most of the people I run across, I guess it is a goose.”

Isabel’s Steinway

In the lovely room that was first called the Blue Room, then was renamed the Gold Room—it celebrates both of Michigan’s colors—there is a fabulous Steinway Grand Style A piano, six feet long, with an inlaid case of Circassian walnut, 42 types of wood in all (from 17 countries), and 12,000 moving parts. Inscribed in Latin above the keyboard in gold lettering are the words “Music is medicine to the troubled soul” and “1913,” the year Cook commissioned it.

Why did Cook have such a piano built when he did not play?

According to Margaret A. Leary, author of Giving It All Away: The Story of William W. Cook & His Michigan LawQuadrangle, he may have had it built for the opera singer and pianist Isabel Hauser, who was certainly Cook’s friend and may have been his mistress. She died in December 1915, shortly after the opening of the Martha Cook Building, leaving Cook so downcast that his family and friends feared for a time that he might commit suicide. It was moved to Martha Cook after his death.

* * *

President Hutchins was one of many who urged Cook to visit Ann Arbor when Martha Cook was complete. “You certainly ought to see the noble building that your generosity has made possible,” the president wrote.

But Cook never laid eyes on either Martha Cook or the Law Quadrangle. He seems to have feared that the buildings, however fine, would still fall short of the images of them that he held in his mind’s eye.

When Dr. Walter Sawyer, the U-M regent who was Cook’s good friend, nudged him to come and see the fruits of his gifts, Cook replied: “No, Doctor, you cannot persuade me. You want to spoil my dream. I shall never go to Ann Arbor.”

Cook died in 1930. A bust of the benefactor, modeled on his death mask, was placed on the north mantel of the Gold Room, where it gazes at the Steinway grand once played by Isabel Hauser.

Sources include Marion L. Slemons, ed., A Booklet of the Martha Cook Building at the University of Michigan(1936); Margaret A. Leary, Giving It All Away: The Story of William W. Cook & His Michigan Law Quadrangle (2011); James Tobin, Michigan Law at 150: An Informal History (2009); and the papers of Harry Burns Hutchins, Bentley Historical Library.

Cynthia Farina - 1983

As a former resident, I have waited over thirty years to see the Martha Cook Building gain some attention in a university publication. The building is on the registry of historic buildings and has been referred to as the most beautiful college dormitory in the country. Yet, only the Law Quad gets any attention. Thank you Mr. Tobin and Michigan Today for featuring “Martha Cook” and reminding readers about the gem that sits on U of M’s campus.

Reply

Anne Wolfe - 1980

I was a “cookie” in 1980, and enjoyed its traditions, some of which I hope survive. Most of all I enjoyed the candlelight procession at Christmastime, going up the many stairs with candles – real candles then –and singing carols, collecting “cookies” as we went, and going to the top–the fourth floor, and then all the way back down, with all the girls in solidarity, singing carols by candlelight. It was beautiful. Then there was singing “grace”‘ together before every dinner – which we were required to attend well-dressed–and having tea, coffee and dessert after dinner. and something I seldom missed was Friday afternoon teas, where the law quad students were invited over, though many did not “mingle” and you could invite a guest, even a favorite professor. Every month we had a special dinner where one could invite a favorite professor – many felt honored to come. Of course there were only afternoon visiting hours for the male sex, and plenty of time to focus on studies, which was the main reason students chose that dorm. I often used the great little library on the fourth floor. I loved the plush curtains, the view of the statues, the piano, hearing it occasionally – its stateliness. We were a good bunch overall.

Reply

Lynn Swanson - 1976

My aunt, Elsa Swanson, LSA 1925, spoke of those candlelight processions, which reminded her of her Swedish background. Thank you for the memory!

Reply

Ann Gough - 1984

I lived at Martha Cook my senior year and it was an incredible experience. It is a extraordinary building and it is wonderful to see it get the recognition it deserves.

Reply

Tish Lehman - 1986 Ph.D.

I enjoyed the article about Martha Cook, but you really need to write a companion article on the misogynistic images of women in the Law Quad, where marital law is illustrated by an evil mother-in-law separating a handsome young man from his blushing bride. Look at all the stained-glass windows.

Cook brought beauty to the University, but ugliness too.

Tish Lehman

Reply

Thea B - 2008, 2011

I lived in Martha Cook for all four years of my undergraduate career. It was a wonderful and beautiful place. I wish I would have enjoyed its history more when I was a student.

Reply

Kari Dumbeck

My daughter lived in Martha Cook for 1.5 years and I visited many times. The building is beautiful all in all. However, I was saddened to see the years had taken it’s toll on the wooden walls of the main floor great rooms and they were in much need of loving care. My daughter has moved on and will graduate this coming December but I hope the University takes the time and money to rejuvenate those once great walls.

Reply

Lynn Swanson - 1976

Wonderful article! My aunt, Elsa Swanson Cooper (LSA 1925), lived in the Martha Cook house. Her future husband, Lisle Cooper (Dental School 1924) visited her there where they sat on the “sparking” seat, which was still there when I got to sit on it in the 1970s. The yearbooks were still on the shelf, so I got to see photographs of Aunt Elsa from her time there when she invited me to many Martha Cook teas in that beautiful building. She remained active in the house’s scholarship program until her death in 1981 and was very proud to be a “Cookie.”

Reply

Eugenia (Jeannie) Marcus - 1962

It’s been many years since I left U of M and Martha Cook. I have many fond memories. I never knew the origins of the building or the statues or the reason that various items were chosen. I went on to become a physician and a wife, mother, and now grandmother. In retrospect I appreciate the inscription near the fireplace, “Home, the Nation’s Safety”. I was very active in the movement that launched women into the nation’s workforce. For a time the spirit of that inscription was lost, but now is coming back by the realization that home is the underpinnings of all we do for men as well as women. For the safety and security of children and the future generations, this inscription should be foremost in our hearts.

Reply

Susan Boiko - 1978

My friend Fran was able to get a room in Martha Cook her first year of medical school after a sorority proved way too noisy. I was a dinner guest one night and was decked out in my finest attire. What a beautiful home and I’m glad Dr Marcus also enjoyed it!

Reply

Rita Gedrovics Sparks - 1956

I had the privilege of becoming a “Cookie” through a grant enabling women who had to work their way through school to enjoy the genteel atmosphere at Martha Cook and allowing me to establish life-long friendships with this unique sisterhood of women. My husband Norman (1953 Eng.) and I were serenaded by the Martha Cook residents with the “Engagement Song” when I received my engagement ring. Our daughter-in-law Kathleen, the daughter of another Cookie (Terry Stinson Mead ’54) was honored with the same song at the Martha Cook Alumnae Christmas Breakfast twenty-five years later.

Reply

Elinor Reading - 1962

We had a curfew. Was it 10 p.m.? Couples saying good-night filled Portia’s sidewalk. Singles threaded their way through the crush. At one of the compulsory house meetings, director Isabel Quail stood up. The passion out front, Mrs. Quail said, was becoming embarrassing. The crowding was unnecessary. She gestured east, toward the side yard: “That’s what we have bushes for,” she said.

Reply

Irene Dabanian - 1974

It was novel to live at Martha Cook during the roaring 70’s of free love, drugs, and rock and roll. It was a quiet, lovely, refuge from the wild campus days. Not all prudes lived in Martha Cook. (called the “virgin vault” at the time).

It was a great place to live for my last two years at U of M.

Great memories of the place. It was close to the art school until they built a new school on north campus. Still, to have your own room, be able to take dinners late after a commute to Toledo Art Museum for a blown glass class with one of the greatest glass artists-teachers around, all was glory in those last years at Cook. Thanks for being there for me.

Reply

Caroline Dieterle - 1959 LS&A

I lived in Martha Cook from Fall 1956 – 1959, and I loved it for so many reasons: the spirit of the residents, the traditions, the lovely building and grounds – everything. It was for me a wonderful place where one could feel a part of a cohesive group without sacrificing any of one’s independence of thought, action, or choice. I’ve treasured the time I spent there my whole life.

Reply

Brenda Green-Gitter - 1979

I was blessed to call Martha Cook home for three years. As a business school student, the location was fantastic but the traditions at MCB are what I remember about my Michigan days. Olive Chernow, our director, once said to me that I would never live in a building so grand and that is true. My daughter, Anna Gitter (LS&A 2013) became a “Cookie” too and served on the house board as well as an assistant resident advisor. MCB has aged well and my hope is that future generations will continue to appreciate her beauty. What an opportunity and treasure it is to live there!

Reply

Karen James-Malmsten - 1976

I lived at Martha Cook Building between 1972 and 1975 when about 15 of us from Trenton, MI, all lived there at the same time. It was like living in a fairy tale year round: the magnolias in bloom during the spring, the beauty of the gold and red rooms and the 2 story Christmas tree. There was a special song that I taught my sister when she came for Little Sisters Weekend, and she sang it for me not long ago! “Martha Cook Our Building”…I also recall singing grace at supper when we had sit down dinners (which we had most nights), along with Sunday brunch when our family or friends were able to join us. All of these are part of the lovely moments. The history that was all around us, such as the old textbooks in the libraries on each floor. Mrs. Dufell was our house mother the first year, and I remember that she tried to arrange for me to date one of the Navy men who were in town for the game! I still think of the friendships made there.

Reply

Maxine Burnham Gresla - 1956

I was fortunate to live at Martha Cook 1955-1956. I still keep in touch with friends from there, and recall many happy times. I met my husband at U of M, and when I make a small spill on a white tablecloth, he still says, “Martha Cook” to me. We were supposed to be “finished” upon graduation after enjoying the beautiful Cook furnishings! A bonus was sleeping late and still making my 8 o’clocks at LS&A and Ed.School!

Reply

John Marshall - 1962

This article brought to memory my one contact with the women at the Martha Cook Building. I lived in Gomberg House in South Quad from 1958-1962. We worked closely with our “sister house”, Helen Newberry, on most big projects such as: Michigras, Home Coming and Spring Weekend. However, on one occasion in 1961, our social chairman suggested that we arrange a “Mixer” with the women at Martha Cook. After an initial telephone contact, I, as president of Gomberg House that year, accompanied our social chairman, in making the short walk from South Quad to Martha Cook and met with our counterparts in the formal parlor to discuss the proposed event. I do not recall if we held the mixer in Martha Cook or in Club 600, the snack bar – recreation area of South Quad. Although I think it was lightly attended, we considered it a success.

Reply

Catherine Davis - 1970, MM1976

Thanks and kudos to Mr. Tobin for sharing this wonderful description of the beautiful residence hall that many of us called home during our student years. Thank you too to all those who have commented on their memories of the Martha Cook Building (MCB). Together, the article and the comments prove that MCB is truly a wonderful place!

As Mr. Tobin shared, William Cook never returned to Ann Arbor because he didn’t wish to spoil his dream. I think if he visited today, he would discover the reality of MCB is even better than his vision. For almost 100 years, women, proud to call themselves “Cookies,” have created a community and a network of friends which endures beyond graduation and which provides room and board scholarships in excess of $50K annually. He would be pleased, I think, that the Building’s staff, residents, and alumnae have been superb stewards and the Building is still in excellent physical shape. I think he would be proud that we continue to ensure that our college home continues to be a home for University women and that we are participating in the Victors for Michigan campaign, raising monies both to increase our scholarship fund and to continue to preserve, in the words of an old MCB song, “…our building, our dormitory dear.”

Catherine Davis

Volunteer Coordinator; Victors for Martha Cook, Victors for Michigan Campaign

Reply

Joan McDougall Wadsworth - 1956 BA 1962 MA

A very enjoyable article! I was a “Cookie” for my Junior and Senior years . It was a fantastic experience living and working there! (I worked in the Kitchen and waited on tables those years, also.) My room mate was Joan Muranaka and since we shared a “Joan M.” mailbox and phone extension there were occasional moments of confusion. We had the double room on the mezzanine in back overlooking the tennis court which was great also. Having moved many times since Ann Arbor days (1952-6) I have since lost touch with all my friends from Ann Arbor days so if you were a “Cookie” in 1955-7 give me a “holler” and we can compare partial memories of those days. Joan

Reply

Jo Anne Heywood Miller - Class of 1968, graduated 12/67 - BS Mathematics

I lived at MCB my junior and senior years and loved most of it! I still have several MCB friends and am so glad that the Building and the Garden still exist. I was ‘judiced’ twice – once for being caught barefoot in the main hallway while trying to find a dorm-mate who had an important call on the one outside line and once for having a bottle of wine in the refrigerator after I turned 21! Mrs. Quail loved my boyfriend ( now my husband of 55 years) and was so concerned that my messy table manners would ’embarrass’ him in his career, that she took me to her apt. one afternoon for ‘fork lessons’. I knew about the antisemitic views of Mr. Cook from a dear Jewish friend who moved to Betsy Barbor rather than MCB. It was a great place to live and I am glad it has stayed a women’s dorm!

Reply