Not a fan

The University of Michigan Chimeswas a little student weekly that published sketches, essays, poems, and literary reviews. Nobody paid much attention to it, at least not until a senior named Neil Staebler took over as editor in the autumn of 1925.

Staebler had grown up in Ann Arbor at a time when the biggest man in town — the biggest man in the state — was the football coach Fielding H. Yost. But Staebler never became a fan of Michigan football.

That was like a boy raised by Barnum & Bailey who wasn’t a fan of the circus.

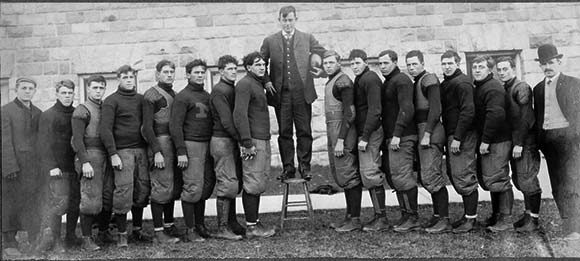

In 1905, the year Staebler was born, the Yostmen — as The Michigan Daily liked to call the varsity — had an off year, for Yost. They went 12-1. (From 1901-04 the team’s record had been 43-0-1.) In the 20 years of Staebler’s youth, Yost’s teams tied nine games, lost 29, and won 114.

Yost was widely seen not only as a great coach but also as a great man, a builder of character in the young and a champion of athletics for all — all men, anyway … well, all white men. (The son of a Confederate soldier, Yost allowed only a small handful of black athletes to play for Michigan, and only in sports less conspicuous than football.)

Now Yost was also Michigan’s athletic director. In the fall of 1925, at the age of 54, he was working crazy hours and running all over the state in pursuit of a huge new achievement.

Most people in town were rooting for him. Neil Staebler was not.

“Tickets! Tickets!”

Americans had gone nuts for college football, and a stadium race was under way. Colossal palaces had been built or planned at Yale (70,896 seats), Ohio State (75,000), and Illinois (92,000), among others.

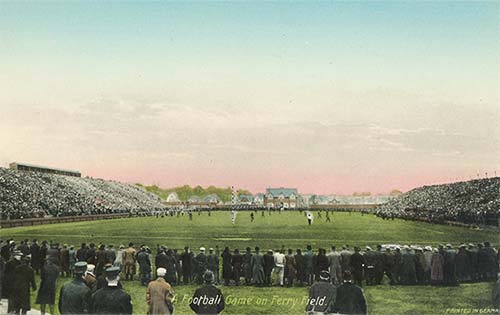

Despite additions, Ferry Field was too small to meet fans’ urgent demand for seats. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Michigan students, Michigan alumni, and people with no direct connection to the school mobbed home games. In 1922, half the entire student body of 11,000 went to the Ohio State game — in Columbus. When Michigan played at home, special trains discharged carloads of fans from across the Midwest, and every Ann Arbor bedroom was crammed with extra cots, bunks, and blankets.

But Michigan’s Ferry Field, beloved as it was, held only 37,000 spectators in the early 1920s. The demand for seats was estimated at twice that number or more, and a cry was rising for some solution to the uproarious demand for tickets.

At first the University’s governing Board of Regents (some of whom requested up to 60 tickets a game for family and friends) said no to any new stadium; the cost would be too high. Maybe more stands could be built at Ferry to meet the need. They were — and the demand for tickets only grew.

When the Wolverines compiled an 8-0 record in 1923 and were named national champions, powerful alumni began to call for construction of a new stadium to seat up to 100,000 fans.

The Yostmen in action

(In this clip, the “Yostmen” scrimmage at South Ferry Field. Kalman Bator Jr. of Detroit, and James O. Simrall of Lexington, Ky., try out as kickers. Team captain George Rich of Lakewood, Ohio, makes a forward pass. Please note: video is silent.)

Yost on the Stump

Coach Yost had an idea to defuse the regents’ fears about the prohibitive cost of a new stadium. To fund construction, he would sell 20-year bonds with a guarantee of two season tickets to every buyer. No student would pay extra. No one would be asked for a donation. No new taxes would be levied. And Yost said football revenue would pay for a grand new complex for other sports and intramurals.

It was brilliant. Alumni were delighted. Students were ecstatic. Marion LeRoy Burton, the University’s popular president and a great friend of Yost, appeared to be on board. The Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics (where Yost enjoyed a strong majority of alumni and students) sent it up to the regents.

Then, early in 1925, President Burton, only 50, died unexpectedly of heart disease.

An artist captured milling fans at Ferry Field just when Neil Staebler was preparing his attack on the stadium plan. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Burton’s interim replacement was the scholarly Alfred Henry Lloyd, dean of the graduate school, a professor of philosophy. Dean Lloyd was not the friend of football or Fielding Yost that President Burton had been, and he called a screeching halt to the stadium charge. He appointed a faculty committee headed by Edmund Day, dean of the School of Business Administration, to study the entire question of athletics at Michigan. After the Day committee had studied and deliberated, Lloyd said, a thoughtful decision about any new football stadium might be made.

At this, Yost went into overdrive. All that spring and summer he gave speeches from Monroe to Marquette to Kalamazoo, pleading his case to members of Rotary Clubs, Kiwanis Clubs, Chambers of Commerce. On the faculty there might be snooty naysayers, but among outstate alumni and just plain fans, he had thousands of allies. Michigan was behind in the stadium race. The state had to compete.

“Whether the stadium is crammed to capacity or almost empty,” he told audiences, “the desire to win by students and alumni is present just the same. It will be a sad day for the youth of America when they no longer want to win. They will become a limp, listless set of boys and girls.”

Yost came off the stump to start the 1925 season. The Day committee met, asked questions, met some more. The regents appeared to be coming around. “You made a mistake when you went in for football instead of the law,” Regent James O. Murfin wrote to Yost. “As an advocate either orally or in writing you have no equal.”

That was when Neil Staebler, 20 years old, became the editor of Chimes.

As his classmates marched down to games at Ferry Field, waiting and watching for what now seemed all but inevitable — an announcement that the Yostmen would soon play in America’s greatest stadium — Staebler got in touch with Robert Cooley Angell, a sociology professor who was barely out of graduate school, one of the youngest members of the faculty.

Knowing the impossibly long odds, and the poisonous treatment they would get from their friends, Staebler and Cooley decided to object.

… Continue reading at heritage.umich.edu.

(Top image: Fielding Yost with the football varsity of 1905, courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Resources:

- The College of Literature, Sciences and the Arts is exploring the role of athletics in higher education with its Sport and the University theme semester.

- The Bentley Historical Library is hosting an exhibit on the early days of student-organized sport at Michigan.

- Among the extensive U-M holdings of the Bentley Historical Library are the Athletic Department archives.

- The papers of Robert Cooley Angell, Neil Staebler and Fielding Harris Yost are housed at the Bentley Historical Library

Jim Conrad - '77, '80, '84

The view out through our backyard in Nashville, TN affords us with the sight of 2 lovely homes built in the early 20th century. The red brick home was lived in by Fielding Yost for several years with the adjacent white Georgian style inhabited for many years by Dan McGugin and family. These Michigan men married the Fite sisters with Mr Yost coaching in Ann Arbor during the season but had his family in Nashville until he became athletic director. The inaugural game for Dudley Field at Vanderbilt, the largest stadium south of the Mason Dixon, took place in October 1922 and featured Michigan and Vanderbilt with the game ball being dropped by a low flying airplane.

Reply

Nancy Boyer-Rechlin

Thank you for the piece on Two Against Football. I must say I am among the minority of alumni who toss out U-M mailings and solicitations — or hit the delete button — when they assume I’m a football fan. In fact, this emphasis had nearly dulled any sense of meaningful association with the university, where I was a student at the School of Natural Resources — and attended just one football game, sitting in the top row of the stadium and amusing myself by watching and photographing the children.

I appreciate the arguments shared in the essays reported, and still regret the overwhelming association of our universities with their football teams. That said, I know individual student athletes who indeed almost worship their coaches and feel they learned meaningful life lessons. But I think that reflects more the character of the individual coach or student than the sport itself. And certainly the linkage of sport with intoxication is a sad fact indeed.

I appreciate whatever you publish that provides genuine food for thought.

Reply

Marti Hearron

I remember Willow Run. YIKES!

Reply

Carol Stoll - NA

We heard stories from our parents and uncles in Detroit about the U of M sports news reels that played in the theater before the feature film. The kicker, Kalman Bator Jr. is my uncle. It’s amazing to be able to see the video and share them with my family and next generation of athletes. Thanks so much for posting.

Reply