Builders’ emporium

Deconstructing the cinematic life of a motion picture can be challenging. Countless aesthetic variants emerge in the creation of a film. It was Russian montagist Sergei Eisenstein who in the 1920s suggested films were “built” rather than shot. Eisenstein was referring to the various stages a motion picture director oversees before arriving at final release: scripting, production design, casting, cinematography, editing, and soundtrack, to name just a few. Over the course of motion picture history each of these components of cinematic construction has developed its own vocabulary for denoting key elements of the filmic process. Full textbooks have been written on each of the “creation” areas.

There’s one though that I still find under-articulated, and that’s the casting of the actor vis-a-vis the captured screen performance.

http://youtu.be/HziqvHUJVOI

(Casting By is a terrific film about Marion Dougherty, a legend in the casting business.)

A moving mosaic

The process of casting can be oddly varied. In some cases, the director interviews and/or auditions talent; in others, a casting agency performs the task. Sometimes talent is cast by type; sometimes against type. Actors may be cast as part of a “talent package” in order to secure financing for a film project. And sometimes an actor is self-cast within a film for which he or she may also be the director or producer.

Casting is central to the filmic process, and finding the words to evaluate the relationship between casting and the resulting screen performance can be tricky. This harks back in part to Eisenstein’s theory that films should be seen and discussed as having been built rather than shot — moving mosaics resulting from piecemeal processes.

Early theories and the non-actor

An early discourse on the film actor argued that successful screen performances were “behavioristic,” with the actor seemingly “caught in the act,” and without the “airs” of a trained artist. In the silent film years the actor was frequently referred to by critics as a “mannequin” or “a maker of faces” and was sometimes even deemed unworthy of the respect or attention awarded the theater actor. Essentially that led to some film directors perceiving a screen actor’s artistic skills as unnecessary.

An early discourse on the film actor argued that successful screen performances were “behavioristic,” with the actor seemingly “caught in the act,” and without the “airs” of a trained artist. In the silent film years the actor was frequently referred to by critics as a “mannequin” or “a maker of faces” and was sometimes even deemed unworthy of the respect or attention awarded the theater actor. Essentially that led to some film directors perceiving a screen actor’s artistic skills as unnecessary.

“The film actor ought not to understand,” Italian film director Michelangelo Antonioni was known to say, “he ought to be.”

Similarly director Federico Fellini is said to have told his actors, “Be yourselves and don’t worry. The result is always positive.”

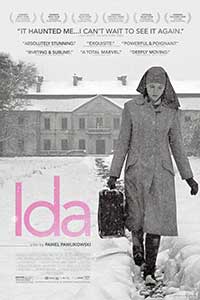

Agata Trzebuchowska’s multi-award-winning performance in last year’s Best Foreign Language Film Ida does lend some credence to a case for the non-actor. Her on-screen Anna — an 18-year-old novice about to take her final vows as a Catholic nun – was the result of pure happenstance. A friend of the director discovered the 21-year-old student of art history and literature reading a book in a Warsaw café.

What about casting a “typed” actor?

And then there is Jason Segel as novelist David Foster Wallace in the welcome summer release The End of the Tour. Prior to this screen role Segel had been pigeonholed (and admired) as a comic actor best known for creating characters caught in a state of “arrested development.” The real-life Wallace was a genial but complex man with a complicated past and a bewildering psyche, hardly a comedic character. In the film, Rolling Stone magazine reporter, David Lipsky (Jesse Eisenberg), travels with and interviews Wallace during the last leg of a promotional tour for his massive 1996 novel, Infinite Jest.

This is essentially a two-character film in which the camera remains riveted on the faces of Wallace and Lipsky. Segel’s rendering of Wallace is nothing short of brilliant — a man seemingly trying to speak openly about himself, but then pulling back. The character Segel presents is that of someone clearly cautious and uncertain about how to offer himself up as a celebrity target for the popular media.

In seeking to understand a character’s internal life, motivations, and persona, most theater actors engage in a number of research techniques to uncloak and reveal the “character spine.” For Segel, Wallace’s own Infinite Jest revealed several critical clues he could use in his film performance.

One revelation Segel has shared in interviews, including an August 6, 2015, article in The Washington Times, was that Wallace could talk “very, very eloquently about depression and suicide … he (had) an emotional vocabulary for things we don’t know how to express.”

Segel came to see Wallace as an enigmatic figure whose “true” self could never be fully known. As he told Entertainment Weekly (July 29, 2015): “There are certain things I could relate to. Specifically the idea that you never know the fundamental anyone. You know how you perceive them, but you don’t know what it’s like to sit in their skin at home when they’re alone at night.”

And by presenting a character whose spine is shaped by deeply nagging internal conflicts, Segel captured the essence of this man on film.

The casting of Segel against an evolved character “type” proved pure genius, and it says a lot about the roles motivational strategies can play in the realization of an unforgettable film character.

What about casting the seasoned film actor?

This past summer’s movie roster included two other films that lead to further thought on casting and the screen performance: Woman in Gold and Ricki and the Flash. Neither was a great film, but each shared a common attribute — a legendary film actor in the lead role who, film after film, has continued to amaze.

Helen Mirren in Woman in Gold portrayed real-life Jewish refugee Maria Altmann, who bravely sets for herself the task of reclaiming from Austria a painting of her aunt by Gustav Klimt. In Ricki and the Flash Meryl Streep played a mother who has abandoned her husband and three children to pursue her dream of becoming a rock star.

Mirren and Streep are both products of drama school. Both are terrific at accents. Neither is considered a “sexy” screen star but both can convey characters with undeniable feminine appeal. How do casting and performance come into play for these two?

For Mirren, her on-screen roles can be seen as a form of self-casting. When scripts are sent for her consideration Mirren is known to opt for roles that depict women of strong independent character. The filmgoer discovers this in one remarkable screen performance after the other: Queen Charlotte in The Madness of King George (1994), Elizabeth II in The Queen (2009), Leo Tolstoy’s wife, Sofya, in The Last Station (2009), Madame Mallory in The Hundred-Foot Journey (2014), and now Maria Altmann in Woman in Gold. All are bold, nuanced characters. And all are voiced with flawless national accents.

Too easy?

Streep, meanwhile, has been described as a screen chameleon, capable of bringing vivid life to any character for which she’s been cast. She can do slapstick comedy and she can do deadly serious drama. She sang and danced in Mama Mia! (2009). She played a male rabbi in Angels in America (2003). And now, in Ricki and the Flash, her character has to move from her regular gig as a second-rate rock star (whose day job is checkout clerk at a health-food store) back to her original role as a mother facing the family she abandoned years before.

Streep may sometimes make a film performance seem too easy — some say calculated — but rarely does one come without acclaim, a fact verified by 19 Oscar nominations. The range of Streep’s talent could be sensed early on in her performance of small-town Pennsylvania working girl, Linda, in Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978). It was a very minor role, one for which Streep was cast so she could be near her partner at the time, the late John Cazale, who played Pennsylvania steelworker, Stan. Cazale was terminally ill with cancer and Streep wanted to nurse him through the filming.

It has been widely stated in accounts of The Deer Hunter’s production that in casting Streep, Cimino encouraged her to improvise her dialogue in a key scene with Robert DeNiro, who portrayed the newly returned Vietnam soldier, Michael. According to one account, director Cimino told Streep to write her own lines when Michael visits Linda in her small house trailer where, among other bits of conversation, they talk about Linda’s boyfriend, Nick, who has mysteriously chosen to stay in Vietnam. The scene is emotionally raw, and clearly improvised, as the two characters search for the words to express the personal impact the war is having on their lives.

Within the Hollywood Vietnam war film genre that scene has no equal in conveying the elemental confusion brought on by a distant tragic war. It is worth seeing the film again to recognize Streep’s on-screen brilliance. She received a Best Supporting Actress nomination.

Streep has spoken from time to time about character motivation when approaching a screen role. As Margaret Thatcher in The Iron Lady (2011) the actress says her interpretation of the former British Prime Minister as an ice-cold, sly persona came in part from the discovery that the political leader reined in her emotions because she was a woman. To be too open personally might have prevented Thatcher from being taken seriously. Streep’s hard-edged performance won her a third Best Actress Oscar.

The Stanislavski Method

Prior to The Iron Lady Streep had won the Stanislavski Prize at the Moscow International Film Festival in 2004. The award is named for the famed Russian actor and theatre director Constantin Stanislavski. It recognizes an artist who, using Stanislavski-style training principles, has achieved greater realism in character interpretation by combining psychological attitudes with learned technical skills. The guiding tenet of the prize is that it be awarded to someone “for conquering the heights of acting and for faithfulness.” Other actors who have received the prize include Mirren, Jack Nicholson, Harvey Keitel, Jeanne Moreau, Gerard Depardieu, and Catherine Deneuve.

If you think about these Stanislavski award winners and reflect on what they’ve contributed to cinema over the years, it’s possible to better understand the degree that film acting has come to be appreciated and considered as worthy of praise as that of a proscenium performer.

Note: Frank Beaver’s April 21 column featured a review of Mark Harris’ history of Hollywood in WW 2 titled Five Came Back: John Ford, Frank Capra, John Huston, William Wyler, and George Stevens. Currently the Turner Classic Movie Channel is running a series on each of the directors and their films. Michigan Today encourages you to revisit Beaver’s column and tune into TCM on Tuesdays at 8 p.m. through the end of September.

Alexander Chrisopoulos - 1974

Casting, Film. Movies. I am ready to be cast. Contact me.

Reply