Be mine…

Valentine’s Day is nearly upon us, and with it, all thoughts turn to love. What better dispels the chill dark of winter than a heart-shaped holiday, with its celebration of devotion and the bright light of romance?

Of St. Valentine himself — a figure martyred in third-century Rome — little is known for certain. He was the patron of affianced couples and of happy marriages (as well as of beekeepers and those suffering from plague); since the Middle Ages, he has been associated with the idea of courtship, and on Feb. 14 we honor that ideal.

The subject has been central to the art of poesy: Think of Penelope and Odysseus, of Helen and Paris in Homer’s great epics, or the vast archive of the troubadours. No poet worth her or his salt — think of Sappho, Robert Herrick, Elizabeth Bishop — fails to embrace the topic, and much of lyric poetry has yearning at its center. I don’t mean to suggest, of course, that every poet writes only and always of love, but it’s fair to say that passion (whether for God or nature or another human being) is one of the genre’s great themes.

This holds true for drama as well. Star-crossed lovers such as Romeo and Juliet or Tristan and Isolde may die of a fateful and instant attraction, but their alliance lives on. Almost every romantic comedy and bedroom farce ends with the lovers united; the curtain descends on a happy embrace and the curtain call has star and starlet holding hands. Cary Grant and Grace Kelly, Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan all belong to a long list of couples who couple at film’s end…

Turn the page

For the novelist, however, this is not always the case. To take just three American classics, Moby Dick, Huckleberry Finn, and The Red Badge of Courage, the matter of “romance” is small and the focus elsewhere. In such European masterworks as War and Peace or Bleak House, the love one character feels for another is subordinate to the titular topic, as if courtship is an afterthought. One could argue that Jane Austen always writes about “the marriage plot,” but Joseph Conrad never does, and the married women of Virginia Woolf or Gustave Flaubert (as in Mrs. Dalloway or Madame Bovary) scarcely exalt the condition. So let me name a few books — the tip of the iceberg, really — that do take love as their subject and write of it at length.

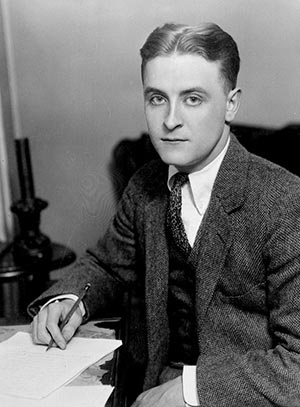

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is suffused with the light of romance. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera is a paean to enduring devotion, as is Scott Spencer’s Endless Love. What strikes me about these stories, however, is how resolutely they resist the fairytale conclusion that their characters “live happily ever after.” When Cinderella weds her prince or Sleeping Beauty wakes again, we’re urged as readers to believe that everything thereafter will be peaches and cream and unending delight. The novelist, however, suggests there must be a next chapter, and it’s not always glad.

Fiction thrives on complication and opposing points of view. The course of true love, as the Bard informs us, “never did run smooth.” No book I know deals with wholly placid amity — a love affair without any sort of obstacle or change. Consider the problems posed by infidelity, indifference, infatuation, or my personal favorite: indiscretion. Let’s stay with that last word a while.

Tell all

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word indiscretion first entered the language in 1340. “He sall never erre by fantasye ne by indiscrecyone,” avers a gentleman called Hampole, translating from the French. Perhaps because of its French origin and by association, in 1825, the word is defined as “the holiday term for vice,” and that’s how we hear it today. Those arbiters of language, the editors of the O.E.D., say the word “in early use” means “chiefly want of discernment or discrimination; in later, want of judgment in speech or action; injudicious, unguarded, or unwary conduct; imprudence.”

Yet the act of indiscretion is not always or only a “holiday … vice.” What was the release of the Pentagon Papers or Edward Snowden’s revelations if not indiscreet? Is a home truth blurted out always and only a problem; is indiscretion even possible in a digital world where all records are maintained and subject to subpoena?

Mostly what seems notable is the antique diction here. Indiscretion may remain a headline-grabber: Think of President Clinton or Congressman Weiner, the whole host of D.C. denizens so eager to resign and “spend time with the family.” But it seems likely that — long before an additional 600 years — the term will become obsolete. It’s almost so already; in a world of blogs and tweets and facebooks and reality TV, the idea of indiscretion feels old-fashioned, nearly quaint. The tell-all me-moirs of never-ending instagrams and selfies and snapchats rule the commercial roost; the practice of confession — once hedged in privacy — has now become a public spectacle. You can’t be indiscreet alone; you need an audience. With so many of us so ready and willing to bare our innermost thoughts and record our most intimate acts, what room remains for discretion, that “better part of valor?”How, in fact, do we define the term; what might it mean today?

My own most recent novel, The Years, takes as its topic the romance of a couple who meets in college and has a brief affair. It does not end well. Then, 40 years later, they meet again and, as aging adults, “tie the knot.” I based the story on The Winter’s Tale, Shakespeare’s great and late “Romance,” wherein the statue of Hermione comes back to life and takes her husband’s hand. The curtain falls shortly thereafter, and the audience is urged to believe that all manner of things will be well.

But “happily ever after” is rarely (except, perhaps, on Feb. 14) the novelist’s last line…

Andrew Bulleri - 1960, 1961, 1968

My wife Kathryn and I got engaged on Valentines Day in1968, We have been married 47 years.

Reply

John Hanley - 1985 1992

The license plate on our mini-van has had the block M followed by LUVRS for some years now. We always told our children that it was because we met and fell in love on the campus of The University of Michigan. The truth was somewhat more indiscreet, of course …

Reply

Gerta Schlitz

Delbanco’s examples of the books that “do take the subject of love and write about it at length” are all written by men. In fact, the article contains 14 references to male authors, compared to three references to women. Perhaps this is because, as Jennifer Weiner so eloquently pointed out in a recent New Republic article, when men write about love and feelings, it’s Literature, but when women write about it, it’s fluff (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jason-pinter/jodi-picoult-jennifer-weiner-franzen_b_693143.html).

Reply

G.M. Freeman - 1950

Cool it, Gerta, it is wholly unnecessary to engage in the numbers game as to gender references. It’s getting old and does not enhance the feminist movement.

If the numbers were reversed would you be unhappy? I doubt it. We need to get off the Hillary track and be realistic.

Reply