Proof positive?

In the late 1980s when I was young assistant professor at U-M, one of my graduate students was interested in studying the effects of omega-3 fatty acids (from fish oil) on coronary risk. To get funding we wrote several pharmaceutical companies hoping to be one of the first research teams to investigate the many fish-oil effects that were starting to appear in the press.

We received a small contract from a Japanese pharmaceutical company. They supplied all we needed: fish-oil capsules, identical-looking placebo capsules that even smelled the same, and enough money to pay subjects for participation, publishing costs, and travel expenses to present our results at a scientific conference. OK. I was up and running. The dean was happy with the overhead money turned over to the department, my graduate student was happy, and I was thrilled. We completed the study with positive results: High doses of omega-3 fatty acids improved immune function (Nau KL 1991).

In the ensuing years I pursued other industry-sponsored contracts to support my research. I even was paid to serve on industry advisory boards and make presentations at scientific meetings about my research. As I look back, I’ve always wondered if the industry funding I received influenced “positive” results from my lab, always in favor of the funding source?

Does industry-sponsored research necessarily introduce built-in conflict of interest, and are scientists who accept industry support necessarily “corporate stooges,” whether they realize it or not?

Industry-funding effect

To promote sales, businesses necessarily support research. Some create their own in-house research facilities with state-of-the-art equipment and highly paid scientists with unlimited support. Others find it more cost-effective to outsource research to universities with built-in research infrastructures and available talent. Industry often goes to great lengths to perform due diligence regarding which studies to fund. Studies that don’t stand a fair chance of producing positive findings are unlikely to be funded. So it should occasion no surprise why industry-funded study findings so often tend to be favorable. No industry that wants to stay in business is likely to fund research where there is not at least a fighting chance of a favorable result.

The “industry-funding effect” describes this close correlation between results of a study desired by the funder and the reported results of that study. This funding effect is robust, particularly for drug- and food/beverage-sponsored research. For example, drug company-funded studies are about four times more likely to reach a pro-industry conclusion than independently funded studies. The statistics are even worse with food/beverage industry-funded research where funding is approximately 4-8 times more likely to be favorable to the financial interests of the sponsors than research without industry funding.And get this, not one of the interventional studies with industry support regarding soda or milk had an unfavorable conclusion. You read that correctly. Not one beverage industry-funded research study reported results that were neutral or negative. Coincidence? Maybe.

Since last March, best-selling author Marion Nestle, distinguished professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University, has been looking at this topic. In her blog, Food Politics, she reports on food industry-funded research, and tallies the findings. Want to guess the results? So far, since mid-March 2015 the score includes 95 studies with results favorable to the sponsor’s marketing interests as opposed to just 9 with unfavorable results. Coincidence? Maybe.

Unwitting partners?

The role of a university-based researcher has changed dramatically over the years. As public funding of research diminishes, researchers face pressure to find increased funding to support their research enterprise. This includes supporting graduate students, post-doctoral scientists, purchase of laboratory equipment, and contributing to their own salaries (as well as to administrative salaries in the department). It even includes buying one’s way out of teaching assignments in order to do more research. Generating external research funding has now become part of a professor’s job description. Tenure decisions often link to how much external monies are generated.

As industry-funded research contributes a bigger portion of the university research enterprise (compared to public expenditures), professors may find themselves in a difficult position. The desire for career advancement (“first to publish” and “publish or perish”), and more recently, the monetization of science for personal gain, has confused the whole research process, introducing potential bias and/or conflict of interest into the equation.

To funded recipients, however, these effects are almost always unconscious, unintentional, and unrecognized, making them especially difficult to prevent. Researchers point to the peer-review process that largely determines which research is published as a way of preventing bias and conflict of interest.

Prior to publishing a paper, and in some cases even presenting at scientific meetings, researchers are required to fill-out “conflict-of-interest declaration forms” stating how their research was funded and if any of the investigators received financial support. The goal of all of this is to provide transparency, so that readers can judge the objectivity, or lack thereof, of any published work. Researchers argue that this transparency and the peer-review process protect against conflict of interest.

Does peer review prevent conflict of interest?

Scholarly peer review (also known as refereeing) is the process of subjecting scholarly work to the scrutiny of other experts in the same field, before the research is published in a journal or as a book. Critical peer review is often the sole criteria for a given research paper to be accepted for publication, considered acceptable with revisions, or rejected for publication. Peer review requires a community of experts in a given field who are qualified, willing, and able to write impartial reviews. Most researchers who regularly publish partake in the peer-review process; it is both a privilege and part of a professor’s professional service contributions. While hardly perfect, the peer-review process allows knowledgeable peers to evaluate the scientific merit of a research paper independent of its funding trail.

Most researchers welcome and trust peer review — it is the best way for research to be evaluated by knowledgeable evaluators. Competent reviewers are able to pass judgment if the topic is important; if the hypotheses tested are relevant; if the methodology is reliable and valid; if proper statistical tests were applied; if the full data are presented; if the study findings were interpreted correctly and not overstated or misstated; whether limitations of the study and outcomes were acknowledged or overlooked; and finally – whether the research warrants publication.

To most researchers, these are the questions that count – not who funded the study, or what the personal relationship of the authors were to the funding source. If the research meets scientific standards required by the journal and the peer reviewers have done a thorough job of vetting all of the relevant aspects of the research, the funding source should be irrelevant — the research findings should stand on their own merit.

Moreover, peer review is not the only mechanism that provides checks and balances on bias and conflict of interest in research. Clinical trials have to be registered; study protocols have to be vetted by ethics committees; sites are monitored (including random and targeted checks by regulators); primary data sources have to be archived; raw data may have to be made available to the reviewers (or even the public); and data monitoring boards must ensure participant safety. All of these checks and balances, it is argued, should reinforce public trust and support for the scientific process. So, seeing a statement of industry funding on a research paper should not automatically taint the results of the study. Should it?

Conflict of interest, behind the scenes

In addition to direct research funding by industry, many researchers receive additional revenue behind the scenes to participate on company boards, serve as consultants and advisers, or appear as speakers at various events.

In some cases researchers and academics are paid for producing opinions and research reviews, or introducing “new” ways of looking at topics of interest supporting industry products. It is difficult to foresee at the onset how this type of industry funding may affect one’s work and credibility. Suppose, for example, that I study the effects of physical activity on weight control (which I did), and suppose my research showed that physical activity is an important factor in trying to maintain calorie balance (which it did). This research can be taken out of context to shift the narrative away from the role of food and diet as the major co-contributing factor in the obesity crisis. Thus, this research can be used in advertising to suggest (to the public) that to maintain a healthy weight people need only get more physical activity and worry less about the food they consume. This is, in fact, a message embraced by the food and drink industry.

Two recent articles in the New York Timesillustrate this exact scenario. The first (Aug. 9, 2015) describes the support by Coca-Cola of academic researchers who founded an organization, the Global Energy Balance Network, to promote physical activity as a more effective method for preventing obesity than calorie control by way of avoiding sugary sodas. The second (Sept. 5, 2015) analyzed emails obtained through open-records requests to document how Monsanto, the multinational agricultural biotechnology corporation, on the one hand, and the organic food industry, on the other, recruited professors to lobby, write, and testify to Congress on their behalf. Both articles quoted the researchers named in these reports as denying any influence of industry funding.

These are clarion examples of how industry-funded academic research can be used by industry to change the narrative to confuse the public and to “manufacture doubt” about the science so that it becomes more difficult to establish regulatory limits or guidelines on consumption and health outcomes.

The Coca-Cola “paybook”

Currently, the soda industry’s primary strategy is to shift the blame for obesity away from consuming too much junk food and on to a lack of physical activity. Last month Coca-Cola disclosed payments of millions of dollars to 115 researchers and health professionals. Specifically, Coke spent $21.8 million to fund pro-industry research and $96.8 million on partnerships with health organizations, including $2.1 million directly paid to health experts.

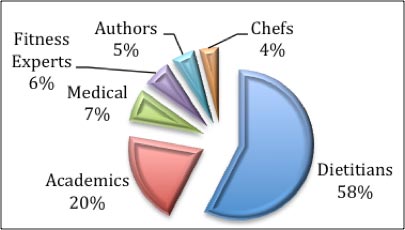

Of the 115 individuals Coca-Cola identified as funding:

Of the 115 individuals Coca-Cola identified as funding:

- 58% were dietitians

- 20% were academics

- 7% were medical professionals (mostly doctors)

- 6% were fitness experts

- 5% were authors

- 3% were chefs

- 1% were chefs/food representatives

Each of these individuals, I’m sure, fervently believes they do not willingly participate in research bias or produce misleading data. While this may be true, some could argue they are being paid to spread a pro-soda (sugar) message. Usually this takes the form of producing research that downplays negativity about soda. So producing research, for example, on the importance and effectiveness of physical activity to influence body weight, or to emphasize energy expenditure rather than energy intake of any kind, would support Coca-Cola’s attempt to focus attention away from any possible negative effect of sugar drinks. In this way Coke can position itself as a positive force in health promotion.

Coke also supports authors whose work draws attention away from junk food as a health culprit. Examples include The Hunger Fixby Dr. Pamela Peeke, a paid Coke consultant who defends sugar against unwarranted scrutiny; or The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier,in which Dr. Carl Lavie, also a paid Coke consultant, debunks the media’s hyper focus on junk food as the obesity culprit. As Dr. Lavie says, “Marked declines in physical activity is by far the major cause of obesity, not sugar and fast foods.” Sarah-Jane Bedwell, a nutritionist and Coke consultant, posted about her love for Coke in an article in a women’s health magazine. And she describes Coke as a “healthy beverage option” in her book Schedule Me Skinny: Plan to Lose Weight and Keep It Off in Just 30 Minutes a Week.

Avoiding conflicts of interest

In response to publicity generated from questions of possible conflict of interest, several scientists and nonprofit research organizations have proposed conflict-of-interest guidelines for protecting the integrity and credibility of industry-funded research. Eight guiding principles have been enumerated.

- Researchers should conduct or sponsor research that is factual, transparent, and designed objectively, according to accepted principles of scientific inquiry.

- Require control of both study design and research itself to remain with scientific investigators.

- Not offer or accept remuneration geared to the outcome of a research project.

- Prior to the commencement of studies, ensure that there is a written agreement that the investigative team has the freedom and obligation to attempt to publish the findings within some specified time frame.

- Require, in publications and conference presentations, full signed disclosure of all financial interests.

- Do not participate in undisclosed paid authorship arrangements in industry-sponsored publications or presentations.

- Guarantee accessibility to all data and control of statistical analysis by investigators and appropriate auditors/reviewers.

- Require that academic researchers make clear statements of their affiliations.

In a world where industry-funded research is increasingly the norm, it is critical researchers adhere closely to these guidelines to maintain scientific integrity and best serve the public interest.

References:

- Als-Nielsen, B., 2003. “Association of funding and conclusions in randomized drug trials.” Journal of the American Medical Association; 290:921.

- Bekelman, J.E., 2003. “Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: A systematic review.” Journal of the American Medical Association; 289(4):454.

- Brownell, K.D., 2012. “Thinking forward: The quicksand of appeasing the food industry.” PLoS Med. 9(7):e1001254.

- Harbour, R., 2001. “A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines.” The BMJ; 323:(7308):334.

- Freedhoff, Y., 2011. “Partnerships between health organizations and the food industry risk derailing public health nutrition. Canadian Medical Association Journal; 183 no. 3.

- Krimsky, S., 2005. “The funding effect in science and its implications for the judiciary.” Journal of Law and Policy 13(1).

- Lesser, L.I., 2007. “Relationship between funding source and conclusion among nutrition-related scientific articles.” PLoS Med. 2007 Jan.; 4(1):e5.

- Lexchin, J., 2003. “Pharmaceutical industry sponsored and research outcome and quality: Systematic review.” The BMJ; 326:1167.

- Lipton, E., Sept. 5, 2015. “Food industry enlisted academics in G.M.O. lobbying war, emails show. New York Times, Sept. 6, 2015.

- Lo, B., Field, M.J., Eds., 2009. “Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice.” Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Michaels, D., 2006. “Manufactured uncertainty: Protecting public health in the age of contested science and product defense.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; 1076:149.

- Nau, K.L., 1991. “Effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on plasma lipid levels in adults with heart disease.” Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention; 11:15.

- O’Connor, A., 20154. “Coca-Cola funds scientists who shift blame for obesity away from bad diets.” New York Times, Aug. 9, 2015.

- Popkin, B., 2011. “Agricultural policies, food, and public health.” EMBO Reports; 12(1):11.

- Rochon, P.A., 1994. “A study of manufacturer-supported trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of arthritis.” Archives of Internal Medicine; 154(2):157.

- Rowe, S., 2009. International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) North America Working Group on Guiding Principles: “Funding food science and nutrition research: Financial conflicts and scientific integrity.” Nutrition Reviews; 67(5):264.

- Sinclair, U., 1935. “I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked,” (Farrar & Rinehart, 1935), (University of California Press, 1994).

- Yank, V., 2007. “Financial ties and concordance between results and conclusions in meta-analyses: retrospective cohort study.” The BMJ; 335:1202.

Gordon Hassing - 1969 Ph.D. Biological Chemistry

I wish to complement the author on a very balanced and well thought out statement. I know how this works from both sides, as I worked in industry for my entire career (Procter & Gamble). If the necessary precautions are taken, as Dr. Katch outlines, the published work can stand on its own. It is still difficult to prevent others from “spinning” the science to their own ends.

I would add that while peer review of papers submitted for publication is a good thing, there are many problems with it and poor work gets published anyway. This is reflected by increasing concerns with errors in the published literature, no matter who is the sponsor. It depends on the expertise and effort put forth by the reviewers. But in net it’s the best system we have.

Finally, the eight steps outlined to ensure a robust system are excellent. In my experience with the University, this is in fact the process that is followed. It allows for a good atmosphere for research no matter who is the sponsor.

Reply

sugar pawz - 2010

Coke also supports authors whose work draws attention away from junk food as a health culprit. On behalf of sugarpawz thank you

Reply