One man’s trash…

My wife and I spend summers at our home in Wellfleet, Mass. At the far end of the outer cape, the village of Wellfleet spans a land-spit barely three miles wide. It sits between Cape Cod Bay and the Atlantic Ocean; freshwater ponds lie between. The vegetation is salt-laved: scrub oak and pine, cranberry, bayberry, and poison ivy in sand. The hills are low, the dunes high.

My wife and I spend summers at our home in Wellfleet, Mass. At the far end of the outer cape, the village of Wellfleet spans a land-spit barely three miles wide. It sits between Cape Cod Bay and the Atlantic Ocean; freshwater ponds lie between. The vegetation is salt-laved: scrub oak and pine, cranberry, bayberry, and poison ivy in sand. The hills are low, the dunes high.

The Cape Cod National Sea Shore has protected much of the area, but all remains at risk. The roads are clogged with traffic, the aquifer diminishes, and the cliffs erode. In this fragile ecosystem, the issue of garbage disposal is of major consequence, and what used to be the “town dump” is now an elaborate facility for which one pays an annual fee, and to which I make a pilgrimage each week.

It’s no casual procedure. Most of us have long since accepted the concept of recycling and that it makes sense to reduce the amount of waste we as consumers produce. Increasingly, we divide what can be salvaged from what we consign to a landfill; we separate glass from newspaper from plastic and so on.

But the Wellfleet Transfer Center and Recycling Station carries this practice to extremes, and to pass through its portals — a gate unlocked at posted hours, a long drive up a hill with a guardhouse at its summit, inspection by a quasi-military sentry — is to relinquish choice.

A portable radio blares; the compacting processors hum. There are great green bins with labels — Newspaper and Cardboard, Plastic and Tin — that will be compacted on site. There are tables for empty bottles and jam jars and clear and colored glass containers, as well as buckets where you leave the caps and corks. There is a table for used light bulbs and one for worn-out batteries. There are men who supervise this process of distribution and tell you what you’ve done wrong.

The way of waste

(Image via: wellfleetrecycles.blogspot.com)

Wearing yellow armbands and green vests, these men monitor particular items for specialized disposal, pointing to the further reaches of the site. There are places where oyster shells get dropped; spaces for yard waste and Styrofoam and tree stumps; and locales for metal, glass, and electronic devices. A TV set or broken microwave will cost $10 to dispose of at a designated shed.

There’s a “Swap Shop” — open every other afternoon, from 2-5 p.m. — where you can deposit books, old CDs, or furniture that someone else might welcome. Of course you are encouraged to forage for leavings you then carry home. But these items must pass the hard muster of the sentinel within.

Finally, there is a reeking pair of 40-foot-long sunken metal containers where you throw your trash. This must be bagged in special purple plastic sacks (of various sizes and available for purchase in the Wellfleet Market). And when the receptacles are filled to capacity, they get forklifted onto 16-wheelers and trundled off the cape.

Grizzled locals in their pick-up trucks will sometimes violate protocol and dare to throw a cardboard box or mattress over the protective fence and down into the bins. But part-time residents — this one, at any rate — tend to follow orders. Indeed, I take a kind of pride when watchmen nod in approval at how well I’ve separated the plastic bottles for recycling from those that can be returned for deposit, how thoroughly I’ve rinsed a jar of marmalade or a tin can of beans. . .

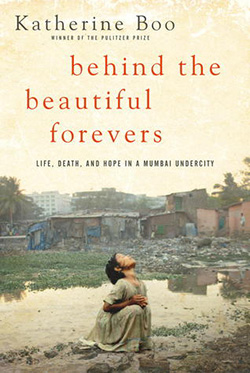

Behind the Beautiful Forevers

Katharine Boo, in her 2012 Pulitzer Prize-winning account, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, details, as her subtitle suggests, “Life, death, and hope in a Mumbai undercity.” There she describes the camaraderie and competition of a group of dump-dwellers who forage for survival.

Katharine Boo, in her 2012 Pulitzer Prize-winning account, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, details, as her subtitle suggests, “Life, death, and hope in a Mumbai undercity.” There she describes the camaraderie and competition of a group of dump-dwellers who forage for survival.

In our prosperous nation, the stakes are less high — but there’s still a cadre of those who pick over what others discard and, as the old song puts it, “get some cash for your trash.” These “regulars” sip cans of soda and complain about the weather and traffic and rehearse the Wellfleet news. I sidle up and grin at them, making what I think of as informed remarks about the town council or the run of striped bass and bluefish — remarks which are, invariably, greeted by affable, absolute silence. They stare and turn away.

Driving down the hill away from the landfill, windows shut against the stench of it, I congratulate myself on having completed my task. I am, after all, helping to organize the planet. “The order of ordure” — I try out a phrase — “the composition of compost, the transfer of trash, the way of waste.” There’s something deeply gratifying about such distribution. Every item has its place and all can be redeemed.

This is absurd, of course. We make small difference here. Rumor has it that the 16-wheelers hauling garbage lump everything together after our dutiful sorting. And day by week by month the waste accumulates again. But as the air clears and I open the car windows, I’m seized by the conviction that what I’ve done is similar to what I also do each day: distribute words on a page.

Writers attempt to make sense — phrase by sentence by paragraph by chapter — of the arrangement of language. We try to fashion order out of jumbled inexactness. An adjective here, a pair of adverbs there, a dangling participle or inexact parallel clause — all these must be pruned in the interest of clarity. Each overlong sentence can be compacted and by editing reduced.

“Since feeling is first,” wrote E.E. Cummings, “who pays any attention to the syntax of things?” But the syntax of things was his subject (“will never wholly kiss you,” as the next phrase in his poem proclaims) and we’re told to pay attention nonetheless.

When I enter that guarded compound — the Wellfleet Transfer Station and Recycling Center — I’m subject to inspection as well as introspection. When I leave, I leave with a sentence both processed and complete. And can start piling trash for the next.

Phil Brown - 1970 UofT

Nicholas, I enjoyed reading this essay on the “way of waste”. I fully understand your take on our need to organize what we no longer need. Thanks for the great read. Here is a parallel thought for you as well: http://wp.me/p41ooi-he

Enjoy!

Reply