Circa ’66

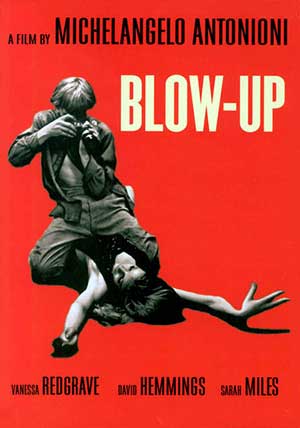

In looking back 50 years, it is interesting to consider just how far Italian filmmaking had inserted itself in all facets of cinematic art at the time, narratively and aesthetically. In fact, I find it hard to believe five decades have passed since Michelangelo Antonioni’s pivotal film Blow-Up arrived in theaters to both activate and puzzle filmgoers around the globe. The “mod masterpiece” earned two Oscar nominations that year, but took nothing home.

In looking back 50 years, it is interesting to consider just how far Italian filmmaking had inserted itself in all facets of cinematic art at the time, narratively and aesthetically. In fact, I find it hard to believe five decades have passed since Michelangelo Antonioni’s pivotal film Blow-Up arrived in theaters to both activate and puzzle filmgoers around the globe. The “mod masterpiece” earned two Oscar nominations that year, but took nothing home.

The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences presented its 1966 Oscars on April 10, 1967, at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. The tenor of the evening was very much a traditional one, with a sizable portion of the Academy Awards going to two films adapted from stage plays: A Man for All Seasons earned six Oscars, while Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? took five. Screen adaptations of popular novels dominated the major category nominations, notably, The Sand Pebbles with eight, and Hawaii with seven. All in all, it was a typical Hollywood night at the Oscars.

Blow-Up earned Antonioni nominations for Best Director and Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen (Antonioni with Tonino Guerra). Federico Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits was singled out for Color-Film Costume Design (Piero Gherardi) and Color-Film Art and Set Decoration (also Gherardi). Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew had three nominations: Black-and-White Art Direction (Luigi Scaccianoce), Black-and-White Costume Design (Danilo Donati), and Musical Score (Luis Enrique Bacalov). Each of these films deserves a look back.

The Gospel According to St. Matthew

Of the three iconic Italian films cited for Oscar nominations in 1966 The Gospel According to St. Matthew remained closest to the original styling and intentions of neorealism. Piero Paolo Pasolini first introduced his humanist styling in Accetone (1961), a film he scripted and directed. Its story was that of material corruption, dramatized through a young pimp (Franco Citti) who wants to earn an honest living, but tragically fails. Pasolini cast non-actors and employed an unadorned shooting style in filming the episodic story.

For a social-realist account of the life of Christ, Pasolini also chose non-actors and a direct style of filming that favored facial compositions. His visual inspiration drew on 14th-century biblical painting, notably Giotto and Masaccio, as the film traces the life of Christ from the Nativity to the Resurrection. The narrative follows Christ (Enrique Irazoqui) as he journeys along the Sea of Galilee with his disciples, sharing the scriptural lessons taken from Matthew’s gospel. Christ’s teachings are delivered with a forceful Marxist conviction that speaks to social injustices, corruption, and materialism.

In his New York Times review (Feb. 18, 1966), Bosley Crowther wrote of Pasolini’s treatment: “For this time the story of Jesus is told in the simple and naturalistic terms of a plain, humble man of the people, conducting a spiritual salvation campaign in an environment and among a population that are rough, unadorned, and real.”

It was Pasolini’s austere, black-and-white, artist-inspired cinematic visualizations that earned The Gospel According to St. Matthew its Oscar nominations for Costume and Art Direction. The Musical Score nomination was for a diverse pastiche of classical, religious, and popular music selections that included, among others, Bach, Odetta (“Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child”), and the Aramaic Yom Kippur service declaration “Kol Nidre.”

Juliet of the Spirits

Federico Fellini’s affinities for mixing fantasy and realism emerged in the 1960s at the same time that other Italian filmmakers were turning away from neo-realistic “this-is-the-way-life-is” styling and themes. Fellini’s poetic imagination, inspired in part by his love of the circus, was fully on display in his self-reflexive, loosely structured 1963 fantasy film 8 1/2. Interior thoughts rule the story of a film director who is plagued by “director’s block” and erotic obsessiveness.

8 1/2 was the beginning of what critics and historians have referred to as Fellini’s “confessional” period of filmmaking, and Juliet of the Spirits can be seen as a continuation of that impulse. The film carried forth a free-flowing structural style as it displayed the interior musings of a woman (Giulietta Masina, Fellini’s real-life wife) who lives with a philandering husband and, consequently, a troubled psyche. It’s a Fellini film unlike any other.

Fellini’s vision was that of an imagined, subjective view of a woman’s sensual thoughts and feelings, revealed through lavishly colored costumes and set decor. Its fantastic, surreal visualizations were the source of its Costume Design and Art and Set Decoration Oscar nominations in 1966. On the release of a re-mastered, restored version of Juliet of the Spirits Roger Ebert wrote of Fellini’s later period of filmmaking: “We see him now as the master of his canvas. He was a storyteller early in his career, but became a painter of moving images, and those who fixate on plots or messages are hunting in the wrong field.” (“Great Movies,” August 5, 2001).

Blow-Up

As with many of the acclaimed Italian directors of the time, Michelangelo Antonioni had made documentaries and written scenarios during the country’s burst of neorealist effort in the 1940s. By contrast Blow-Up would arrive on screen as part of Antonioni’s later body of work, which eschewed starkly realistic social thematics for psychological studies that centered on the wealthy — often women who are restless and bored, living in environments that serve as stultifying correspondents for the characters’ emotional malaise. In these films, traditional plotting was minimal, resolve boldly ambiguous.

Antonioni’s much-acclaimed trilogy L’Avventura (The Adventure, 1960), La Notte (The Night, 1961), and L’Eclisse (The Eclipse, 1962) gave incontrovertible evidence of these characteristics, and of a filmmaker fully committed to using the screen as expression for a modern age.

Blow-Up, Antonioni’s first all English-language film, also spoke to modernity, borne in large part through its setting in 1960s Mod London. Boredom and disillusionment gnaw at the film’s protagonist Thomas (David Hemmings), a successful fashion photographer who is looking for new direction in his life. His job of filming beautiful models is treated by Antonioni as an act that combines work with erotic body language.

Blow-Up’s action takes place in a single day during which we learn Thomas is preparing a portfolio that will embrace social realities. As he ventures from his studio, he is seen snapping photos in a London park where he inadvertently takes shots of a man and a woman seemingly caught in a love tryst. The woman (Vanessa Redgrave) attempts to retrieve the exposed film and raises Thomas’ suspicions about the couple and a possible crime. Curious, he sets about enlarging his frames until the images are reduced to grainy abstractions — images that lead Thomas back to the park to investigate what he may have seen in his blown-up film prints.

This fragmentary “mystery” component is only a part of Blow-Up’s take on a disillusioned man’s day in 1960s London. Entering the mise en scene are stalking would-be teenage models, a music club scene with the Yardbirds, an angry Jeff Beck (unforgettable!), and numerous traveling shots as Antonioni’s camera sweeps through the neighborhoods and streets of London.

Mod, moral, and masterful

Blow-Up was a breakthrough in a variety of ways. Its openly suggestive treatment of sexuality made a significant impact on the direction of candor in screen content. Moral watch groups would condemn the film, even as it was drawing big audiences in the U.S. and around the world.

Aesthetically Blow-Up offered a brilliant example of the extent to which abstract coloration in a film’s art/production design can create both atmospheric and thematic values. The scenes in Thomas’ studio were rendered in pale bluish-white tones. This design effect lent a clinical aura to the setting that enhanced both the film’s psychological tenor and the “investigative” subplot. By contrast, the exterior pallet is vibrant and “alive.” As Thomas drives around London in his Rolls Royce, we see unnaturally green landscapes and buildings awash in bold, expressive tones.”

Thematically Blow-Up provoked viewers to think about film, its ambiguities and perceived realities. And all this came with jazz pianist Herbie Hancock’s original, multi-styled musical score.

Altogether Blow-Up was an exciting, surreal exercise in enigmatic filmmaking that 50 years later remains hypnotic. It may not have taken home any Oscars, but it did win the Grand Prix at Cannes.

Matthew Zivich - 1960, B.S. in Design

Thanks for this article. It’s a reminder of how great it was to see these movies at the time, and to have been a part of this special period in cultural history.

Reply

Carole Tavris

Dear Professor Beaver,

I am a UM Alum (social psychology, 1971), and a friend sent me your article about classic films, including “Blow up.” My husband, Ronan O’Casey, was the blow-up — the man in the park whom Vanessa kisses before he’s killed.

Ronan had a great back story about that film, which he wrote to Roger Ebert years ago; Ebert loved the letter and published it in his column.

Reply