It is difficult to identify foods high in “added” sugar

We’ve all seen those “Where’s Waldo?” puzzles. We know he’s there — hiding in plain sight — but he’s difficult to find amid the myriad details designed to distract us.

We’ve all seen those “Where’s Waldo?” puzzles. We know he’s there — hiding in plain sight — but he’s difficult to find amid the myriad details designed to distract us.

In much the same way, sugar appears throughout the modern diet, though we often fail to “see” it. Whole, processed foods, such as milk, fruit, vegetables, and some grains contain naturally occurring sugar. (Fructose is one of the most common natural sugars; you’ll find it in fruit. Another common natural sugar is lactose, which you’ll find in milk.)

Processed and prepared foods often contain added sugars and syrups to enhance flavor. Most of this sugar comes in the form of high-fructose corn syrup and ordinary table sugar (sucrose).

The average American consumes 22-28 teaspoons of added sugars daily (equivalent to 350-440 empty calories per day; and about 70 lbs. per year). In my previous Health Yourself columns “You’re sweet enough already” and “Addicted to food,” I discussed the various kinds of sugar, how addictive they are, and why you should reduce your sugar consumption. But as you’ll soon discover, it’s hard to reduce your sugar consumption if you can’t tell how much you are consuming.

Sugar peddlers are very skilled at hiding added sugar, much like Waldo, in plain sight. They lobby government officials responsible for U.S. food policy to make finding added sugar as difficult as possible. They pour millions of dollars into legislators’ coffers to curb legislation and regulation, especially when it comes to children. These industry lobbyists deliver “research” and publish papers to confuse and mislead the public. They hire surrogates to deflect criticism and change the narrative.

They even have the gall to suggest added sugar is OK!

The new food label: Still difficult to understand

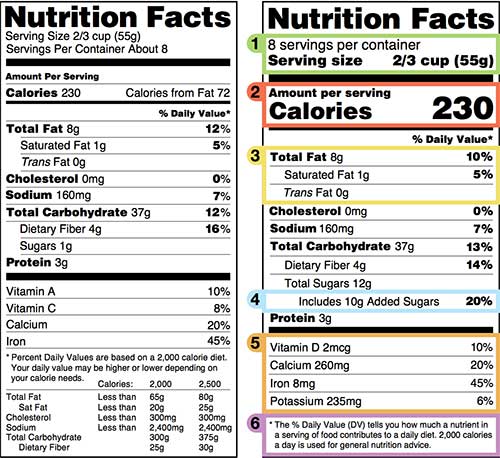

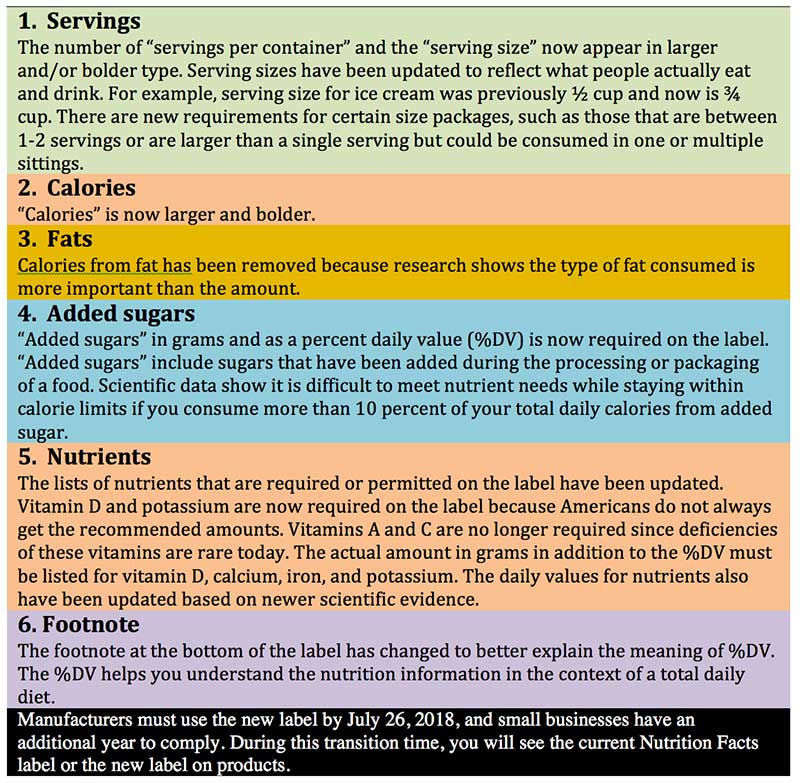

For the last nine years the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with input from nutrition scientists, has been working to revise the standard food label and make it easier to identify added sugars. This latest food label, pictured below (right) as a side-by-side comparison with the previous label, has one “really big” change: a new line for “added sugar.” (See #4 in the figure.) The change is designed to distinguish between sugars that are naturally occurring in a food and the sugars that manufacturers add to a food.

How many foods have added sugars?

A team of researchers at the University of North Carolina conducted a detailed survey of packaged foods and drinks purchased in American grocery stores. They found 60 percent of products included some form of added sugar. That’s right: 60 percent. WOW!

When they looked at every individual processed food in the store, 68 percent had added sugar. The list included many sauces, soups, fruit juices, and even meat products.

Some foods include “regular sugar,” (i.e., table sugar or sucrose). But many manufacturers use different products that are nutritionally similar. We have become familiar with high-fructose corn syrup, the most common added sugar, made from processing corn. There are less familiar added sugars like “evaporated cane juice,” which appears in many yogurts. “Rice syrup” and “flo-malt” are added sugars, but are less obvious to the casual consumer.

Words that just mean ‘added sugar’

Below is a list of coded terms used by different food producers to connote added sugar.

- agave juice

- agave nectar

- agave sap

- agave syrup

- beet sugar

- brown rice syrup

- brown sugar

- cane juice

- cane sugar

- cane syrup

- clintose

- confectioner’s powdered sugar

- confectioner’s sugar

- corn glucose syrup

- corn sweet

- corn sweetener

- corn syrup

- date sugar

- dextrose

- drimol

- dri mol

- dri-mol

- drisweet

- dri-sweet

- dried raisin sweetener

- edible lactose

- flo-malt

- fructose

- glaze and icing sugar

- golden syrup

- gomme

- granular sweetener

- granulated sugar

- high-fructose corn syrup

- honey

- honi-bake

- honi-flake

- inverted sugar

- isoglucose

- isomaltulose

- lactose

- liquid sweetener

- malt

- malt syrup

- maltose

- maple syrup

- mizuame

- molasses

- nulomoline

- powdered sugar

- rice syrup

- sorghum

- sorghum syrup

- starch sweetener

- Sucanat

- sucrose

- sucrovert

- sugar beet

- sugar invert

- sweet ‘n neat

- table sugar

- treacle

- trehalose

- tru sweet

- turbinado sugar

- versatose

The sugars on this list are not always meant to confound consumers. Instead, many of these sugar types are chosen by food scientists to give their products the best flavor and texture. Some sugars are better for baked goods, while others taste better in soft drinks. Some are also cheaper than others.

Beware of juices

Fruit juice concentrates are drinks that have been stripped of nearly everything but sugar and then evaporated. An example would be “apple juice concentrate” — which is just “liquid sugar” with little nutritional value, sometimes described as “empty calories.” The new-and-improved food label should help consumers be more aware of the amount of sugar found in these types of juices. And remember: Even if the product is labeled “natural” or “organic,” it’s still just sugar.

Here is a list of “juice concentrates” that are just other names for added sugar.

- apple

- acerola

- apple cider

- apricot

- aronia berry

- banana

- blackberry

- blackcherry

- blackcurrant

- blood orange

- blueberry

- boysenberry

- cantaloupe

- carambola

- cherry

- chokeberry

- clementine

- coconut

- cranberry

- date

- dewberry

- elderberry

- fig

- goji berry

- gooseberry

- grape

- grapefruit

- guanabana

- guava

- honeydew

- huckleberry

- kiwi

- lingonberry

- lychee

- mandarin orange

- mango

- mangosteen

- marionberry

- melon

- mulberry

- nectarine

- orange

- papaya

- passion fruit

- peach

- pear

- pineapple

- pink grapefruit

- plum

- pomegranate

- prune

- raisin

- raspberry

- strawberry

- tangerine

- watermelon

A healthy dietary pattern

The new federal dietary guidelines released in 2015 urge Americans to consume a “healthy dietary pattern” containing certain types of foods. According to these new regulations, hidden added sugars make it difficult to understand if the foods we eat are part of a healthy eating pattern.

As you might guess, many of the big food industry groups and the sugar industry – particularly the corn refiners who produce much of the high-fructose corn syrup – are not happy. In a recent statement, the Sugar Association said it was “disappointed” by the FDA’s decision to require a separate line for added sugars. The association argued the rule lacked “scientific justification.”

Soft drink producers are particularly incensed. A 12-ounce can of Coke has 140 calories and 39 grams (1.3 oz.) of sugar, equivalent to 9.2 teaspoons!

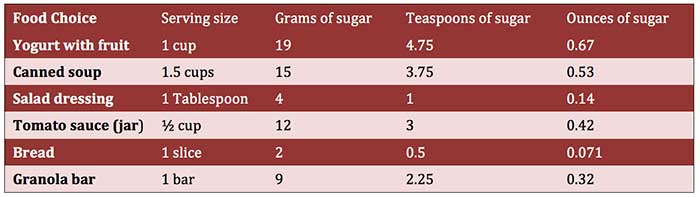

The sugar lobby won a victory, however. And it’s a victory that should keep consumers as confused as ever. The new rules permit companies to express sugar in grams, not in teaspoons or ounces. Most Americans have no idea of equivalency between grams and ounces, or other common measures.

For your information, one gram equals 0.0353 oz. (divide grams by 28.35 to get ounces). Four grams of sugar (4.2g to be exact) equals one teaspoon.

The table below includes six examples of different foods, one serving size, and the equivalent sugar content.

Most consumers would be surprised, I’m sure, by the large amounts of added sugars in products that are generally thought of as “healthy” — foods like infant formula, protein bars, and yogurt.

The new food label should help.

We can only hope.

References:

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020. FDA: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

- Popkin, Barry M., and Hawkes, Corinna. (2016). “The sweetening of the global diet, particularly beverages: Patterns, trends, and policy responses for diabetes prevention.” Lancet: Diabetes & Endocrinology. 4(2),174. PMCID: PMC4733620

- http://time.com/4130043/lobbying-politics-dietary-guidelines/

- http://harvardmagazine.com/2015/02/dietary-guideline-recommendations-2015

- http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/21/health/fda-nutrition-labels.html

Paul B

In the sentence “For your information, one gram equals 0.0353 oz. (divide grams by 28.35 to get ounces), or 4.2 teaspoons (divide grams by 4 to get teaspoons.)”, your math does not add up… dividing grams by 4 would result in .25 teaspoons, not 4.2 teaspoons. Which is correct?

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Four grams of sugar equal one teaspoon. MT regrets the error. (Ed.)

Reply

John M - 83, 84

Extremely informative and helpful! Thank You!!

Reply

Rork Kuick - 79, 83

I did not follow why the left label had 1 g sugar and the right one 12 g.

I do bemoan the fact that my fellow citizens seem to like sugar in almost everything. It means that most processed foods are to their liking, and not to mine. Salt is similar.

Reply

Maureen Wood - 84, 88

The only answer that makes sense is that “sugars” on the old label only included naturally occurring sugars, and that “added sugars” didn’t have to be disclosed at all — hidden in the total carbohydrates. Hence the “Where’s Waldo” title to the article. If that is the case, then I too, as many of you I imagine as well, have been duped for a LONG time, thinking that these “other carbohydrates” were something OTHER than sugar. No wonder these changes are being forced on food producers. Just another example of why certain regulations are necessary. If people would just do the right thing in the first place, this wouldn’t be necessary.

Reply

Rork Kuick - 79, 83

I’m more openminded about it being just a typo, or fantasy. Sugar is still sugar.

Reply

Brian Gawronski - 1976

Comparing the nutrition labels, the definition of “sugars” must have also changed. How did 1 gram on the old label convert to 10 or 12 grams on the new label?

Reply