Opening lines

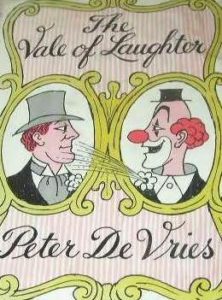

“Call me, Ishmael,” is the opening sentence of a comic novel by Peter de Vries (1910-93). The Vale of Laughter (1967) — itself a not-so-veiled reference to “The Vale of Tears” — begins with, “Call me, Ishmael. Call me anytime, day or night.”

The narrator here refers, and not obliquely, to the first three words of Herman Melville’s book about a peg-legged mariner and white whale. “Call me Ishmael” — one of the most famous opening lines in the history of literature — is an authorial imperative to the 19th-century reader, sounding a clarion call. By inserting a comma into Moby-Dick’s first sentence, however, the 20th-century author fashions a personal request from one character to another. No member of the crew of Melville’s foredoomed whaling ship would have had a telephone. We get the joke.

De Vries used this strategy often. With several other titles — Without a Stitch in Time (1972), I Hear America Swinging (1976),and Sauce for the Goose (1981)— he took a phrase and twisted it for satiric effect: adding or substituting a word or letter to a well-worn phrase. Further, he titled a 1983 novel, Slouching Towards Kalamazoo,which is a good-humored cap-tip to William Butler Yeats’ poem, The Second Coming,and its final question: “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last/Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”

I’ve heard that somewhere . . .

The beast is not so much born as wittily reborn, refashioned with a wink. Add a comma, change the name of a city, and two of the dark masterworks of English literature become an inside joke. When Joan Didion calls a collection of essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, her 1968 description of life in Southern California is titled without irony; we take the reference at face value. Yeats and William Shakespeare — to take just two examples — have provided numberless titles for other authors’ texts. I won’t provide the sources or the dates of publication, because the list would grow too long.

Here are just a few from Shakespeare:

- Remembrance of Things Past

- Salad Days

- Nothing Like the Sun

- Fools of Fortune

- Pale Fire

- Brave New World

- Not so Deep as a Well

- The Dogs of War

- The Ides of March

- The Sound and the Fury

- The Moon is Down

- Cold Comfort Farm

- Infinite Jest

Here are a few from Yeats:

- Things Fall Apart

- No Country for Old Men

- The Golden Apples of the Sun

- The Dying Animal

- About My Table

- When the Green Woods Laugh

- The Widening Gyre

The beat goes on

Peter De Vries was marching to a different drum, and those readers who might recognize the phrase “a different drummer” may remember that it comes from Waldenand Henry David Thoreau.

There’s a 1962 novel of that name by William Melvin Kelley, a 1971 RCA recording of that same name by Buddy Rich, the “Big Band” drummer; there’s — to take just two examples — a “Different Drummer Tattoo Parlor” in Cape Girardeau, Mo., and a cooking school, “Different Drummer’s Kitchen,” in Albany, N.Y. Our speech, our shops, our book titles, and recordings all incorporate such referents: What we hear and say and write is almost unavoidably a form of repetition: “variation on a theme.”

Try to write a paragraph with no such echo or association. Try to have a conversation using no word you’ve not used before. Try to listen to a song or look at a picture that reminds you of nothing you’ve previously heard or seen, and you’ll perceive the problem. Everything is interlinked and has some verbal resonance; all of us live with the past. We are creatures with retentive memories, and those who have no such facility — who live in the perpetual present — are limited and even, in a literal sense, maimed. “What’s past is prologue” (another quote from Shakespeare), and woe betide the man or woman with no sense of what went before. Amnesia strips us of our memory, but the sentient individual is full of “echo and association” — a phrase I’ve now used twice in one paragraph. We repeat others as well as ourselves.

Original sin

More broadly, we move from the copyist’s task to our own individual vision. No one seeks to be original when learning the scales, or how to mix paint properly, or where the comma belongs in a subordinate clause. Only a few will teach themselves to walk or talk or drive a car, not to mention the rules of tennis or hygiene or chess. We take for granted, as a culture, that certain skills need to be learned, and we do so via emulation, moving from the copycat’s game of “Simon Says” to the youthful author’s earnest effort: “Simon Writes.” There’s nothing shameful — indeed, much to be admired — in homage to a master or a rehearsal of previous work. Most teaching strategies are predicated on instruction by way of repetition: Repeat, class, after me.

What, therefore, is this thing we celebrate called “originality,” and why is the word “plagiarist” one of our actionable insults — particularly so in the academy? There was a risible fuss last summer about Melania Trump’s — or more accurately, her speechwriter’s — arrogation of Michelle Obama’s fine rhetoric anent the American Dream.

But in all the fuss and bother no one suggested the lady be sued for her no doubt inadvertent repetition, and Melania held no teaching job she would thereafter lose. Though plagiarism is a sin, it’s also what we learn to do when first acquiring language; we copy and repeat. We make into our common parlance and coin of the verbal realm what some anonymous or celebrated someone coined way back when.

All of us spend, I think — I, myself, certainly did — a good percentage of our youth as copycats or, more grandly, disciples: borrowing this one’s use of metaphor, that one’s delight in the four-letter word; that one’s ear for dialogue and this one’s deployment of brand-names. And at the end of this long process of imitation, admiration, and emulation, there’s a phrase for it: “Good writers borrow, great writers steal.”

(How about you? Have you used any words for the first time lately? How about anent? Or arrogation? Can you add to the writer’s list of common phrases borrowed from other — and often obscure — sources? — Ed.)