The front page

Given the increased attention paid to the news media in this peculiar time of political maneuvering, I decided to look back on the ways Hollywood filmmakers have portrayed members of the print and broadcasting business.

Generally speaking, Hollywood screenwriters and producers have been respectful of the media, presenting the Fourth Estate – American print, television, and radio organizations — as central, often noble forces in sustaining an informed democratic society.

R-e-s-p-e-c-t

Scanning through motion-picture history one finds a number of film types that can be placed in sub-genre categories.

One popular form comes in the presentation of a “living” news organization whose characters are dimensionally developed as committed professionals and complex individuals. Ensemble films like Network (1976), Broadcast News (1987), and The Paper (1994) fall into this group. These screen creations are usually labeled “comedy-dramas.”

Drawing on factual material to drive an action-based plot about investigative reporting is another sub-category. Here one finds journalistic endeavor of high order: All the President’s Men (1976), The Insider (1999), and, most recently, Spotlight (2015).

A third category depicts the co-opting of journalistic enterprise for self-serving reasons. The two great classics Citizen Kane (1941) and All the King’s Men (1949) are iconic examples. Another is The Fifth Estate (2013).

The comics

First, before I dive into my brief retrospective analyses of these films, I should note that movies, being movies, often have told news-focused stories that harbor no grander intent than to serve up 90 minutes or so of pure screen entertainment. Most recently, we can point to the Anchorman spoofs (2004, 2013), courtesy of comedian/satirist Will Ferrell.

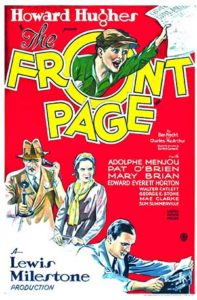

Going way back to 1940, one finds the thoroughly delightful screwball comedy His Girl Friday from Howard Hawks. That picture was an offshoot of The Front Page (1931), a screen adaptation of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s 1928 hit stage play. (Howard Hughes produced the film iteration.)

The bones of both stories are essentially the same. In Hawks’ version, hard-nosed news editor Walter Burns (Cary Grant) strategizes with great aplomb to keep ex-wife and crack reporter Hildegarde (“Hildy”) Johnson (Rosalind Russell) on staff to cover the impending execution of a convicted murderer. He also hopes to forestall her marriage to an insurance salesman (Ralph Bellamy).

In The Front Page “Hildy” is an engaged-to-be-married male (Pat O’Brien). Singularly characteristic of the “screwball comedy” genre, His Girl Friday’s antics play out with witty, barbed male-female repartee, frenzied pacing, and a happy resolve at film’s end. The one serious mention of the newspaper profession appeared in a Variety assessment (March 25, 1931) of The Front Page in which an actual journalist describes the fictional editor as “a cold- blooded story man, knowing only news and believing nothing should get in its way.”

Lawrence Kasdan’s (BA ’70/MA ’72/HLHD ’00) first produced screenplay The Continental Divide (1981) was a screwball-infused, verbal tete-a-tete between a Mike Royko-type Chicago newsman (John Belushi) and a beautiful, brilliant ornithology researcher (Blair Brown) holed up in the Rocky Mountains. At the time of its release, Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert likened the picture to “The Front Page crossed with ‘Lou Grant’ and modernized with a computerized newsroom.” (Jan. 1, 1981).

The lifestyle section

Connecting threads in Network, Broadcast News, and The Paper suggest playbook components common to the development of a familiar type of news media screenplay:

- A team of committed staff members coping with work while dealing with domestic issues: family, personal relationships, aspirational ambitions

- On-site strategies for holding onto and improving audience ratings or newspaper readership

- Corporate concerns about the media organization’s financial health

- Snapshot of the bustling activity and workday tensions common to the news media work environment

NETWORK

Network, written by Paddy Chayefsky and directed by Sidney Lumet, stands at the head of the line in this type of ensemble-oriented news media film. Retrospective testimony to its brilliance came in 2005 when the Writers Guild of America voted Chayefsky’s script one of the 10 best in motion picture history.

A rambunctious (and frighteningly prescient) farce, Network’s plot follows the downward spiral and reincarnation of Howard Beale (Peter Finch), the “Evening News” anchor at the Union Broadcast Systems (UBS) network. Increasingly poor ratings force Max Schumacher (William Holden), chief of the news division, to remove Beale from his long-held position.

In angry response, Beale announces he’ll commit suicide on the air during his last news broadcast and he encourages his viewers to go to their windows, open them and shout out “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore.” Beale’s rant is taken as a populist Everyman’s cry and soon he’s the heroic star of “The Howard Beale Show.” Studio audiences show up to scream, on cue, the “I’m as mad as hell…” mantra.

Meanwhile, UBS producer Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway) is agitating for her own show, and embarks on an extramarital affair with news chief Schumacher. Network reaches its farcical showdown when an incensed Beale learns that a Saudi Arabian conglomerate is angling to buy UBS. Beale pleads for his populist supporters to lobby the White House and prevent the selloff. To stop the damage to UBS’ corporate plans, Beale is assassinated on air by hired Ecumenical Liberation Army operatives. Christensen’s new show “The Mao Tse-Tung Hour” takes over the Howard Beale time slot.At the time of its release, Network was viewed as an acutely brilliant satire on the commercialization of broadcast news, and the degree to which news executives will stoop to acquire and hold audiences. Most cinephiles would agree that the satire remains as biting today as it was some 40 years ago.

BROADCAST NEWS

Much like Network, James L. Brooks’ Broadcast News (1987) can be regarded as a writer’s film. Writer-director Brooks’ screenplay about life in a Washington, D.C., television news department centers on three protagonists: handsome sportswriter-turned-anchor Tom Grunick (William Hurt); spirited writer/on-air reporter Aaron Altman (Albert Brooks); and feisty insecure producer Jane Craig (Holly Hunter). An awkward love triangle ensues as both men are attracted to Jane, and vice versa.

The dramatic force of Broadcast News derives from its inside view of news gathering, combined with nuanced observations of the key characters’ interactions as they deal with the anxiety and responsibility that come with such demanding jobs. The bustling newsroom interplay gains force with Brooks’ brilliant dialogue — a script component that adds comic tailoring and humanity.

The New York Times’ film critic Vincent Canby said of these screenplay qualities: “Mr. Brooks gives his characters the benefit of the doubt. Unlike stock figures, they can send themselves up. Says one reporter to another ‘Would you tell a source you loved them just to get information?’ The immediate response, ‘Yes,’ is followed by laughter all around. In fact, the question remains unanswered.” (Dec. 16, 1987).

THE PAPER

Director Ron Howard’s The Paper (1994), co-written by David Koepp and Stephan Koepp, is a tersely focused day-in-the-life treatment of a financially troubled New York tabloid. It’s a classic tale of editorial integrity versus the almighty dollar. The dilemma on this particular day: How to present the front-page story of an unsolved murder when there are more questions than answers. As deadline approaches the questions come fast and furious: Are the two black teens charged with the crime guilty or innocent? Has there been a police cover-up? Are the teens being framed? And finally, which headline/photo will sell the most papers?

A cast of veteran actors rushes in and out of the journalistic frenzy: Editor-in-chief Bernie White (Robert Duvall), living with prostate cancer; newspaper owner Graham Keighley (Jason Robards), caught in a contract confrontation with managing editor Alicia Clark (Glenn Close); and Metro Editor Henry Hackett (Michael Keaton) being badgered by his pregnant wife Martha (Marisa Tomei) to find a more lucrative, albeit less exciting, job.

Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert must have been familiar with the domestic and personal elements that wend their way into films like Network, Broadcast News, and The Paper. In his review of The Paper he wrote: “The film gets a lot of things right about working on a newspaper, and one of them is how it screws up your personal life. You get cocooned in a tight little crowd of hyperactive competitors, and eventually your view of normality begins to blur. The phrase ‘I’m on deadline!’ becomes an excuse for behavior that would otherwise lack any justification.” (March 18, 1994).

The diligent journalist

The innate appeal of the “procedural” plot makes for riveting newsroom drama, particularly when an investigative journalist is chasing a story over an extended period of time.

Some memorable films with investigative procedural plots include: Henry Hathaway’s Call Northside 777 (1948), in which “Chicago Times” city reporter P.J. “Jim” McNeal (Jimmy Stewart) reluctantly, and then passionately, investigates a 12-year-old murder that resulted in a 99-year prison term for an innocent man (Richard Conte). The movie is based on a true story.

Here are a few more gems you should not miss:

- Richard Brooks’ Deadline (1952), with news editor (Humphrey Bogart) pursuing the link between a woman’s murder and a racketeer (Martin Gable);

- The Parallax View, an Alan J. Pakula film about a political reporter (Warren Beatty) investigating the mysterious deaths of several witnesses to an assassination of a presidential candidate;

- Michael Mann’s The Insider (1999), involving tobacco industry whistleblower Dr. Jeffrey Wigand (Russell Crowe) and a “60 Minutes” television producer (Al Pacino) who prods the reluctant Wigand to expose corruption in the tobacco industry;

- David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007), in which a serial killer sends encrypted, taunting messages to The San Franisco Chronicle staff and city authorities;

- Concussion (2015), Peter Landesman’s adaptation of the 2009 GQ article “Brain Game” by Jeanne Marie Laskas, detailing the lengthy investigation by a Pittsburgh forensic pathologist, Bennet Omalu (Will Smith), into the neurological damage that repeated concussions inflict on NFL football players.

ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN

Few films have raised regard for investigative journalism as much as Pakula’s All the President’s Men (1976) and Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight (2015). Both chronicle true stories.

The Washington Post’s investigation of the June 17, 1972 burglary at the Democratic National Committee Headquarters on the sixth floor of the Watergate complex began when young reporter Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) covers the arraignment of the five suspected burglars, only to discover the men all have ties to the CIA. As fellow reporter Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) joins Woodward in the investigation, the possible involvement of other intelligence and White House figures comes to light.

Woodward seeks inside assistance from an anonymous source, “Deep Throat,” an upper-level government official who has helped Woodward in the past. During their clandestine (and cryptic) encounters, Deep Throat tells Woodward “to follow the money.” That transactional advice leads to the revelation that campaign contributions to Richard Nixon’s Committee to Reelect the President (CREEP) were diverted to underwrite the Watergate burglars’ scheme and earlier efforts to undermine Democratic candidates running against incumbent President Nixon.

The Woodward-Bernstein collaboration led to the 1974 book All The President’s Men, which served as Pakula’s outline for the film. William Goldman’s screenplay reads like a tense procedural thriller, developed around the classic investigative journalism stratagem of What? Who? Who Else Knew? When? To What End?

Now 40+ years on, the power of the film and the book from which it originated still resonate. On the occasion of Post editor Bradlee’s death three years ago, the Chicago Tribune re-published Ron Dorfman’s initial review of the Woodward/Bernstein book: “It is our reward because All The President’s Men demonstrates that America’s journalism can be, and in its crucial hour was, conducted with the highest standards of ethics, the greatest concern for public interest, and a near-suicidal commitment to the pursuit of truth and justice.” (Oct. 30, 2014).

SPOTLIGHT

Many of those same accolades for the process and consequences of dedicated investigative reporting can be applied to Tom McCarthy’s much-admired Best Picture Oscar winner of 2016. The inquiry in the iconic ensemble film centers on The Boston Globe’s team of reporters exploring possible child abuse — and a subsequent cover-up — by Boston-area Catholic priests.

As with All the President’s Men, Spotlight evolves into a suspenseful thriller as the reporters come closer to exposing the devastating truth. Powerful members of the Church issue warnings about the consequences of interfering with Boston’s tight-knit diocese and its administration. Working methodically through their doubts, four reporters pursue separate leads in the investigative effort, culminating in a shocking institutional expose with revelations spreading far beyond Boston’s environs. (For an expanded analysis of Spotlight see ‘Greater Than Its Parts,’ Jan. 21, 2016.)

Don’t stop the presses

There are so many wonderful films about the news. In next month’s column I will share even more of my favorites, including Citizen Kane, All the King’s Men,and The Fifth Estate. Till then, I’d love to hear some of yours.

Catherine Arcure - 1962

What an interesting and timely piece by my favorite film authority. Happy to have a whole new assortment of movies to view. This was great.

Reply