Films to watch this season

The late spring/summer season is well underway for film fans. There are plenty of worthy options for your consideration — hopefully at a theater near you or, in time, in the comfort of your home via Netflix, FilmStruck, or other viewing systems.

Notable among the seasonal fare are Polina and Atomic Blonde, both graphic novels adapted for the screen. And it wouldn’t be summer without some family-oriented animation: Cars 3, Despicable Me 3, and The Emoji Movie, (yes, those emoji characters on your computer spring into action with voice work by Maya Rudolph, James Corden, and Patrick Stewart). In addition, the season’s novel-into-film recasts include My Cousin Rachel (Daphne du Maurier), The Dark Tower (Stephen King), and The Beguiled (Thomas Cullinan).

We also see further evidence of filmmakers’ unending fascination with World War II in Churchill, The Exception (Kaiser Wilhelm II, Heinrich Himmler), Dunkirk, and 13 Minutes (a biopic about Georg Elser’s 1939 attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler). Also, two documentary follow-ups are arriving on screens this summer: An Inconvenient Truth: Truth to Power and Buena Vista Social Club: Adios.

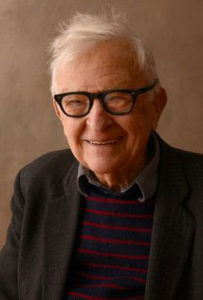

Among the dozens of new releases are four films I consider especially noteworthy. Two represent the final work of longstanding cinema icons: Andrzej Wajda’s Afterimage, and Albert Maysles’ In Tranist, both appearing in general release posthumously. Wajda, the great Polish director, died last October at age 90. Maysles, a master in the direct-cinema documentary film movement, died in 2015 at age 88.

Afterimage

Andrzej Wajda was indisputably the central filmmaker who chronicled Nazi occupation of Poland during World War II and the post-war trauma of Stalinism. In my book about early motion picture history, On Film (1983), I wrote about Wajda’s emerging importance in Polish cinema:

“Between 1954 and 1958 Andrzej Wajda created a remarkable film trilogy about youth heroism and tragedy during the Nazi occupation of his homeland: A Generation (1954) thrust romantic Polish youth into military encounters; Kanal (1957) took them into Warsaw’s sewers during the 1944 uprising; and Ashes and Diamonds (1958) placed a young would-be political assassin at a pivotal point in Polish history.

“Ashes and Diamonds is considered Wajda’s early masterpiece. The young hero’s efforts to kill a Nazi official on the very day the Germans finally vacated Poland — ending instead with his own death — represented an ironic loss of individual spirit in the struggle for a free country. A strong mixture of realism and romantic lyricism in the trilogy created a combined sense of personal and national tragedy.” (p.425)

Wajda’s acclaimed 1981 film Man of Iron centered on Poland’s Solidarity labor movement. The historic drama, underwritten with newsreel footage, recounted the Communist Party’s treatment of Gdansk shipyard strikers in 1980. It received the Palme d’Or award at Cannes in 1982.

Post-war Communist domination of Poland is carried forward thematically in Wajda’s newly released final film, Afterimage. Its title derives from the film’s heroic protagonist — famed constructivist painter Wladyslaw Strzeminski, who defied Stalinist efforts to constrain his avant-garde expression. Godfrey Cheshire, reviewing for rogerebert.com (May 19, 2017) says in praise of the film and of Wajda:

“Afterimage is mounted in a classical, beautifully understated style that throughout conveys the assurance of a true master. It is one of those films that doesn’t ask to be liked or admired. Like Darkness at Noon, Nineteen Eighty-Four, or any other anti-Communist literary classic, its descent into the hell of totalitarianism isn’t softened by a glimmer of solace at the end. It’s the testimony of an artist who has seen the worst of Polish history and demands that it not be forgotten.”

In Transit

Albert Maysles and his brother, David (1931-87), helped spearhead the direct-cinema movement in American documentary filmmaking. Inspired by independent documentarist George Rouquier (Farrebique, 1946), the Maysles approached their subject matter with a spontaneous, naturalistic style that strove to avoid preconceived structuring of content.

Using wide-angle lenses and long-take shots, the filmmakers minimized camera awareness and created an aesthetic distance that allowed the subject or the event to reveal itself within the environment. Guiding voice-over narration was taboo. The direct-cinema approach differed from that of “cinema-verite” where fluid, spontaneous camera involvement was routine.

In the early 1960s, the Maysles discovered a passion for chronicling the lives of artists and cultural celebrities like Orson Welles, the Beatles, Yoko Ono, and Truman Capote. Joined by masterful editor Charlotte Zwerin in the mid-1960s, the Maysles produced some of their most iconic direct-cinema studies.

For Salesman (1969), the Maysles traveled alongside four door-to-door peddlers hawking expensive Bibles in largely low-income neighborhoods in New England and Florida. New York Times critic Vincent Canby wrote that Salesman is “such a fine, pure picture of a small section of American life that I can’t ever imagine its ever seeming irrelevant, either as a social document or as one of the best examples of what’s called direct-cinema.” (April 18, 1969)

Gimme Shelter (1970), with its roving account of the Rolling Stones’ 1969 U.S. tour, offers up another classic example of the Maysles-Zwerin collaboration. After David’s death in 1987, Albert Maysles worked on more than 20 additional documentaries as director and sometimes cinematographer. His next-to-last documentary, Iris (2015), delivered a spirited portrait of the inimitable fashion icon, Iris Apfel.

In Transit, seen in limited venues just before Maysles died in 2015, promises a remarkable final work from an extraordinary filmmaker. In a statement of intent, Maysles said his goal was to board Amtrak’s Empire Builder in Chicago and interview passengers as the long-distance train traveled to the Pacific Northwest — Amtrak’s longest route — in hopes of capturing the “unique community that emerges on trains.”

The working title for this last project was “Lifetime Stories.”

On board, Maysles and his small production crew moved from train car to train car, filming and talking to passengers about what lay behind them, why they were traveling, and what they thought lay ahead. Fascinating episodes involve strangers who meet and begin to share their lives and personal issues with one another. In Transit has been described as a humanistic, intimate, and “gentle” exercise in direct-cinema expression.

In Transit holds special appeal for me. Growing up as the grandson of the Southern Railway stationmaster at Conover, N.C., I always have been fascinated by trains and train lore. My grandfather’s older brother rode Southern Railway trains as an engineer. When we knew he’d be passing by our little village of Elmwood, traveling north from Asheville toward the nation’s capital, we’d watch for the crossing light to change from green to red and head for the railroad tracks. We’d wave proudly, and he always responded with three blasts of the steam-powered train whistle. One of the stops several miles up the way in Rowan County was Barber Junction where a third brother held charge as stationmaster.

That personal history noted, I like the idea that Maysles’ In Transit looks deeply inward, promising a metaphorical view of human nature through the shared experience of train travel.

The B-Side

Another film I’m looking forward to is The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography by renowned documentarist Errol Morris (The Thin Blue Line, 1988; The Fog of War, 2003; and Standard Operating Procedure, 2008).

Standard Operating Procedure investigated the meanings and intent behind U.S. military police photographs taken at the Abu Ghraib prison complex in 2003. The B-Side also centers on significant photographic work, but in an entirely different way. Dorfman, now 80 years old and essentially “retired,” produced photographic portraits with a rare, bulky Edwin Land Polaroid studio camera whose instant-print format was 20 inches by 24 inches. The giant camera and its support frame occupied the space of a small closet.

Working out of a studio in Cambridge, Mass., for more than 30 years, Dorfman employed the artistic and technical range of the unique camera for intimate and wholly natural portraits of her subjects (family and friends, public figures, newlyweds, and graduates). Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg was a subject who became a special friend, as did B-Side’s documentarist Errol Morris.

The lack of essential chemical “pods” required to operate the giant Polaroid has (for the time being, at least) forced a pause in Dorfman’s unusual portraiture career. The B-Side title refers to the 20- by 24-inch portraits left behind (the ones her subjects didn’t select) and which she is thus able to share with Morris.

With B-Side, director Morris intended to pay tribute to the photographer’s singular achievements. He told IndieWire in 2016, “It’s always bothered me that I felt her photography was so fabulous and she was fabulous but she was unknown to a larger public. And this is my attempt to remedy that.”

My own interest in still photography intensified in 1973 when I first read Susan Sontag’s On Photography (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1977). This brilliant essay collection explores how “omnipresent” photographic images have inserted themselves into contemporary life. In one particularly memorable observation Sontag writes: “Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.” (p.23)

I expect that those inherent possibilities in looking at photographs will surface in the Dorfman-Morris exchanges in B-Side.

Detroit

A fourth summer selection is a historical drama that looks back on Michigan history a half century ago. The film is Detroit, a thriller-like recounting of the rioting and civil turmoil that erupted in the city in the summer of 1967.

John Hersey’s investigative book. The Algiers Motel Incident (Knopf, 1968) examined events at the motel (at the intersection of Virginia Park and Woodward Avenue) where a police/National Guard raid on July 25 left three black men dead and nine others badly beaten. Subsequent trials against police officers failed to bring convictions.

Acclaimed author/journalist and Oscar-winning screenwriter Mark Boal wrote the script for Oscar-winning director Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker, 2009). The pair shares a proven track record for dealing with dark, explosive, and unseemly subject matter.

Boal co-authored the story for The Valley of Elah (2007) with director Paul Haggis, a crime procedural about suspected foul play by American soldiers in an Iraqi platoon. Zero Dark Thirty (2012) Bigelow’s followup to The Hurt Locker, again with Boal as screenwriter, was another procedural exercise in which a female operative seeks to find and kill Osama bin Laden.

The combination of Bigelow (known as a visceral director) and Boal (lauded for his gift for detailing character psychology and motivation) gives promise of another intense film experience lifted from history.

Detroit has a large ensemble cast with John Boyega (Star Wars: The Force Awakens, 2015) in a principal role as a security guard. Detroit hits screens Aug. 4.

David Carlyon - 1971

I saw Beatriz at Dinner and Wonder Woman on consecutive days, and I’m surprised you mentioned neither. While you do have limited space and can’t bring up every summer movie, they were both prominently promoted and got respectful-to-rave reviews. I believe Beatriz didn’t deserve much praise, except for the acting, as the filmmaker seemed unclear what his story was. Wonder Woman did deserve praise, for two things especially, for being one of the rare action movies with superpowers that didn’t pull me out of the action to wonder about plausibility, and for having a strong enough, human enough story to nearly be able to stand on that alone, without the superhero stuff. (Like the musical Jersey Boys, which has such a strong book, that it might work even without the 4 Seasons songs.)

I’m eager to see Detroit. I remember late July 1967 before coming to Ann Arbor, I was in Bay City working in a pharmacy that sold liquor. As riots spread north to Flint and Saginaw, and liquor sales were banned, that pharmacy was the closest place that sold liquor, and a guy drove from Saginaw, threw open his trunk, and said, “Fill it up.” Loading boxes of booze in his trunk was a little thrilling and a little chilling, as if the fires were flickering north.

Reply

Michael Klossner - 1968

In your list of the year’s world War II movies, you should have included Their Finest. I will be hard to beat.

Reply