Joe Louis: Boxer, activist, actor, and . . . arena

On July 30, 2017, the iconic Detroit arena fondly known as “The Joe” ended its 38-year existence. Named for the heavyweight boxing champion who held his title longer than any other, the city-owned Joe Louis Arena served as home to the Detroit Red Wings and hosted hundreds of entertainment, sports, and public events. Ronald Reagan accepted his party’s presidential nomination when the 1980 Republican National Convention was held there.

Joe Louis Arena opened in 1979 to replace the Detroit Olympia. “The Joe” closed for good in mid-2017. The venue is succeeded by the new Little Caesars Arena, in Midtown Detroit.

The Joe opened with a Dec. 12, 1979, basketball game between the University of Detroit Titans and the University of Michigan Wolverines, coached by Johnny Orr. Michigan emerged the victor, 85-72.

Four decades earlier Louis had captured the world heavyweight boxing title with an eighth-round KO of Jim Braddock in Chicago. African Americans across the U.S. had clustered around radios to listen to the championship bout and to cheer on their ascendant “hero.”

Take that

Winning the heavyweight title was a sweet comeback for the 23-year-old southern transplant, still reeling from a devastating loss the year before to Max Schmeling (much to the glee of Germany’s burgeoning Nazi regime).

Louis’ victory came after a time when black boxers were prohibited from competing for the heavyweight title.

The ban and attitudes about black athletes, in general, originated in part over racial and press animosity surrounding black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson (1908-15). Johnson’s maverick boxing tendencies and gregarious personal lifestyle generated widespread criticism. (The boxer was the subject of the 1967 Broadway play The Great White Hope and subsequent 1970 film, starring James Earl Jones, BA ’55.)

Louis’ black trainers and managers guided him toward a code of personal standards designed to sustain an unblemished persona: clean fights, modesty after victory, a reserved demeanor at public outings. Louis’ likability and victories in bout after bout (including a 1938 rematch KO of Max Schmeling, two minutes and four seconds in the first round) captivated sports writers who increased their coverage of black athletes. The boxer’s out-of-ring activism for minority rights would factor into his emerging legacy. When a journalist proffered that Louis was becoming a tribute to his race, another fired back, “Yes, a tribute to the human race.”

Backstory 1914-37

Louis (pictured in 1937) held the world heavyweight championship title from 1937-49. (Image: Wikipedia.)

Louis was born Joe Louis Barrow in LaFayette, Ala., on May 13, 1914, to sharecropper parents who were the children of former slaves. Impoverished and living in an environment where the Ku Klux Klan commonly intimidated local blacks, the Louis family moved to Detroit in 1926. They settled on Catherine Street in the city’s Black Bottom neighborhood. Joe was 12.

At age 18, Louis began training in a Detroit boxing gym where his natural abilities caught the attention of athletic trainers and managers. Competing in Golden Gloves and Amateur Athletic Union bouts, Louis won 50 of 54 fights before turning pro in 1934. His only loss was to Schmeling in 1936 before taking the heavyweight title in June 1937. Later that year, the Brown Bomber would fight in front of the movie cameras in a film loosely based on his life.

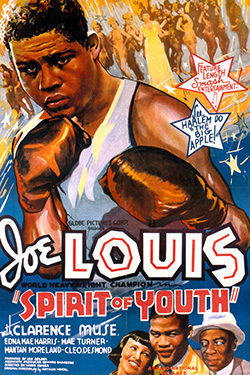

“Poverty Row” and Grand National Films

Grand National Films, one of several B-picture studios known collectively as Hollywood’s ”Poverty Row,” produced Louis’ silver screen debut. Spirit of Youth: The Story of Joe Louis was low budget by necessity. Funds were in short supply to finance sets, costumes, technology, and visual effects. Competing with major studios for sustainable distribution was the greatest challenge on Poverty Row, and most studios had short runs. Grand National produced more than a hundred or so films between 1936-39; unfinished and unreleased pictures went to other studios.

Spirit of Youth showcased an all-black cast portraying screen figures much like the real-life family, friends, and boxing professionals surrounding Louis. The screenplay protagonist, Joe Thomas, follows an impoverished Alabama kid’s “spirited” journey to achievement and fame. In his autobiography, Louis commented on the film’s “rags-to-riches” narrative: “It was supposed to be about a young, poor boy who started out as a dishwasher and wound up champion of the world. I guess it was supposed to be something like my life story.” (Joe Louis, My Life Story with Haskell Cohen,1947, p.80.)

The film: A Black Cinema classic

The so-called B films of the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s have played a significant role in American motion picture and cultural history. Spirit of Youth provides an excellent example of the “magic” that a Poverty Row studio could conjure.

First off, the studio brought the young and shy Louis to Hollywood as a newly arrived sports hero. What I find in the novice actor’s screen persona as boxer Joe Thomas is a natural, convincing portrayal of the modest, unassuming man that Louis’ managers and trainers had promoted him to be. In the screenplay, it’s his mother Nora Thomas (actress Cleo Desmond) who encourages the young boxer to live and fight cleanly and not bring disgrace on his family.

In researching the film’s cast, one unveils a virtual showcase of prominent black actors, singers, and dancers of the 1930s. Actress Edna Mae Harris played Mary Bowdin, a stand-in for Louis’ real-life girlfriend and later wife Marva Trotter whom he had met in Chicago in 1934. Harris had been professionally tutored by the great Ethel Waters. After performing as a regular on the African American Vaudeville Circuit, Harris appeared as a featured vocalist with Lena Horne in Noble Sissie’s Orchestra.

Mae Turner played Flora Bailey, a dynamic nightclub singer who posed a temporary threat to film Joe’s clean-living lifestyle. Turner was a prominent Black Cinema actress known for playing predatory femme fatales.

Arthur Hoerl’s original screenplay for Spirit of Youth also offers an opportunity for sports buffs to match the cast with real people in Louis’ young life. For example, the character of Frankie Walburn (actor Clarence Muse) served as a fictionalized version of Louis’ long time manager John Roxborough. Muse was at that time a thoroughly seasoned, diverse performing artist: film and Broadway actor, screenwriter, director, and songwriter (“When It’s Sleepy Time Down South”). He also held a law degree from Dickinson University. And with Spirit of Youth, he added film composer to his resume, sharing credit for the film’s original score with Elliott Carpenter.

Mantan Moreland, meanwhile, was a popular actor/comedian of the ‘30s and ‘40s. He played the lighthearted role of trainer Creighton “Crickie” Fitzgibbons. Media historians might recognize Fitzgibbons as the perennial chauffeur for the title detective in the Charlie Chan series. Surely the “Crickie” character can be seen as a screen stand-in for Louis’ trainer/confidante Jack “Chippie” Blackburn.

Music and dance — Preserved cultural history

Continuing the Depression-era tradition of turning out inspiring and entertaining movies, Spirit of Youth drew on African American music and dance traditions to embellish its sports narrative. Three popular black music and dance groups appear in the picture: The Plantation Choir, the Creole Chorus, and the Big Apple Dancers. The film opens on an Alabama street where 7-year-old Joe Thomas plays with his friends while the Plantation Choir delivers an a cappella spiritual reminiscent of “work songs” originated by slaves on mid-18th-century plantations.

“Plantation” vocal groups gained popularity on radio and in films in the ‘30s and ‘40s, and this form of traditional black music continues to be performed by contemporary groups. Its background presence at the beginning of Spirit of Youth sets an ennobling tone that was typical of Black American Cinema productions.Black orchestras and chorus girls enliven the musical revues set in the BlueBird Cafe where Joe Thomas is taken by “Crickie” to meet with potential managers. There he encounters star singer Flora. She performs “Blue, What For?” and “Magical Lover” as the Creole Chorus dancers perform the type of synchronized routine most popular at Frank Sebastian’s Cotton Club (1926-39) in Culver City, Calif. (This Prohibition-era venue advertised itself as “featuring the greatest Creole Revue in the West.”)

The Big Apple Dancers perform the third and final club number in the film. “The Big Apple” dance originated in African American culture in the early 20th century. Said to be the eponymous name for a black South Carolina club, the dance had become a national craze by the time Spirit of Youth was made. In 1937, New York’s Roxy Theater — the second largest in the country — booked the well-known Big Apple Dancers for six daily, standing-room-only shows. Dancing to “Spirit of Youth,” written by Muse and Carpenter, eight Big Apple Dancers deliver one of film’s most significant and exhilarating moments of black cultural artistry.

Cinematics

Spirit of Youth isn’t the most dynamic cinematic exercise, but it has much to recommend it as effective storytelling. The narrative arcs blend with the musical numbers as the boxers’ personal and professional lives evolve. One of the most creative and memorable elements of the film is the inspirational musical interlude “Little Things You Do Day By Day,” written and sung by Muse over a montage that reveals Joe’s attempts to come back after a devastating loss. There’s seamless intercutting of staged boxing scenes with archival newsreel footage. A “last-minute” cross-cut editing strategy for the film’s climax has girlfriend Mary being rushed by auto to the boxing arena where Joe has been struggling in the early rounds of the championship bout. It’s a dramatic, funny, and perfect ending to an upbeat, feel-good sports film.

Legacy

Robert Graham sculpted “the fist,” commissioned by Sports Illustrated and unveiled in October 1986. (Image: Daily Detroit.com.)

Spirit of Youth doesn’t tell the full story of Joe Louis’ life and emerging significance as an American hero. But it’s an inspiring preamble to the story of a man whose importance would grow even as he suffered from financial and health-related setbacks during his 66 years as a public figure. And notably, the film survives as a lasting cultural relic of its time.

The day after Louis’ death in Las Vegas on April 12, 1981, President Reagan said in a tribute, “Joe Louis was more than a sports legend: His career was an indictment of racial bigotry and a source of inspiration to millions of people around the world.” (April 13, 1981.)

Among the monuments that stand as tributes to Louis’ place in American history are “The Fist,” a massive bronze sculpture (24 feet long), installed in 1986, that hovers above Detroit’s Hart Plaza. In addition, a representational image of Louis, unveiled on Feb. 27, 2010, stands in the boxer’s childhood hometown of LaFayette, Ala., thanks to a local citizens’ committee that subsidized its funding. The statue outside the Chambers County Courthouse weighs 3,600 pounds and stands 10 feet tall.

References

Joe Louis: My Life Story with Haskell Cohen, NY: Duell, Sloan & Pearce Pub., 1947; The Importance of Joe Louis, Jim Campbell, San Diego, CA: Lucent Books, 1977; Internet Movie Base (IMDb) “Black Cinema.”; and Internet Moving Image Archive.

Bob Syrunkel - 1982

In addition to the Fist, there is a larger-than-life statue of Joe Louis in Cobo Hall. His boxing stance guards the east side of the concourse near the coffee and gift shops.

Reply

David Marlin - 1950, 1957L

I remember the unrestrained joy in 1937 in the small Negro section of New Castle, PA, where my father had his wholesale beer distributing business when Joe Louis knocked out Jim Braddock. I write, however, mainly to thank Frank Beaver for another wonderful movie review and for his magical description of that earlier time.

Reply