Style and substance

If you’re an avid cineaste or a documentary film aficionado, you’ve likely spent time thinking and talking about Errol Morris. From the get-go, Morris has pushed the boundaries of the nonfiction genre.

He reaffirmed that reputation recently with Wormwood, his six-episode, 240-minute documentary screened on Netflix. The artist’s epic inquiry into a man’s lifelong obsession to learn the truth(s) behind his father’s mysterious death in 1953 is pure Errol Morris sleuthing — a landmark exercise in recapitulating the style and substance of a four-decade career in nonfiction filmmaking. Before turning to film work in the 1970s, Morris had been a private detective. I think that helps explain his early interest in dissecting screen topics that can best be described as investigative oddities. The two initial films that launched Morris’ career are telling examples.

Gates of Heaven (1980)

The first feature, Gates of Heaven (1978, released in 1980), comprises interviews with the owners of a failed California pet cemetery, and with the father and son who operated the Bubbling Well Memorial Pet Park where the unearthed remains of the failed cemetery’s pets were relocated. Initiating an innovative and compelling approach to nonfiction filmmaking, Morris eschewed any supplied voice-over narration that would help guide and amplify the subject matter. The interviewees’ own words and personal insights carry the narrative, adding to the innate, albeit quirky, humanism of the interviews. Enormously appealing to both viewers and critics, Roger Ebert declared Gates of Heaven an“underground legend” in documentary filmmaking.

Vernon, Florida (1981)

Equally popular and similarly styled was Morris’ second feature, Vernon, Florida (1981). That 50-minute film was hatched exclusively from interviews with residents of the small Florida town, allegedly known as a place where some locals had fraudulently amputated limbs to collect insurance money. Originally titled “Nub City,” Morris cautiously backed away from that incriminating label and reworked the interviews around the residents’ colorful, homespun stories. Again, Morris earned accolades as a compelling documentarist who was willing to remain an “invisible” presence in his films. Audiences and critics embraced the picture.

The Thin Blue Line (1988)

Pushing the boundaries of nonfiction filmmaking ever closer to the edge of the genre’s map, Morris turned The Thin Blue Line into an investigative challenge reminiscent of his former role as a private detective. He had become intrigued by a 1976 murder in Texas that ended with the death sentence (later changed to life in prison) for 26-year-old Randall Dale Adams. Adams had been charged with the shooting death of Dallas policeman Robert Wood. The facts: Adams was nowhere near the midnight crime site. Sixteen-year-old David Ray Harris, driving a stolen car, had earlier in the day picked up Adams whose car had run out of gas. After spending some hours together, Harris drove Adams back to the motel room he was sharing with his brother. The two Adams brothers were traveling from Ohio to California. Later, the police believed Harris when he told them Adams murdered Wood.

Morris interviewed the principals and drew on the trial testimony of Adams and Harris, police officers, and prosecution and defense lawyers. He combined these direct-eye-contact interviews with an admixture of noir-styled, reconstructions (imagined, with actors) designed around the often conflicting and sketchy trial accounts of the shooting. A Philip Glass score adds an ominous, searching tone to an innovative film that explores the dark side of truth.

The Thin Blue Line revolutionized the way film and TV “true-crime” stories would be treated going forward. And notably, the public outcry after the film’s release led to eventual acquittal and freedom for Randall Adams after 12 years in prison. Although Morris’ film often has been cited as one of the greatest of all documentaries, its reconstructive elements were said to make it ineligible for a 1988 Best Documentary Oscar nomination.

The Fog of War (2003)

Morris’ 21st-century documentaries feature provocative and probing inquiries into American political history centered on personal perspectives of the country’s divisive wars. Best Documentary Oscar winner The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert McNamara (2003) drew on the former U.S. Secretary of Defense’s philosophical observations about warfare based on his service as a whiz kid in World War II. He also served as defense chief under Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. McNamara’s time in Washington coincided with the Cuban Missile Crisis and the lengthy Vietnam War. Many considered McNamara to be the latter’s principal architect and sustainer.

Based on 20 hours of interviews, McNamara proffered 11 generalized commentaries on situational warfare without singling out a specific conflict. Among the topics: “just” wars; excesses of war; human fallibility; and the challenges of terrorism. Morris presented McNamara as the data-driven prodigy he’d once been in war and as president of Ford Motor Co. To catch visual innuendo in the interviews, Morris used his camera invention — the Interrotron — that could capture through two-way mirrors both interviewee and interviewer so that each appears in direct-eye contact with the other and with the viewer. Candid and often seeming regretful, 85-year-old McNamara comes across as remarkably introspective.

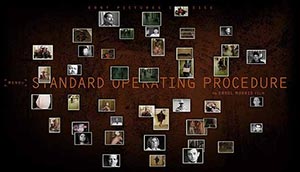

Standard Operating Procedure (2008)

Standard Operating Procedure looked back epistemologically at the scandalous photographs taken by U.S. Military Police inside Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison in 2003. In addition to interviews with U.S. soldiers and Iraqi prisoners, Morris again sought to recapture the essence of the story with reenactments of Abu Ghraib torture sessions. He defended his choice to film scripted reenactments on a Hollywood set: “I’m asking us to think about Abu Ghraib. Photos are the restless little pieces of the world, stripped of all context, stripped of before and after, right and left, top and bottom . . . And it’s my attempt to tell a story visually, to bring that photo back to life, that’s being attacked.” (Joshua Rothkopf, “Time Out New York,” April 24-30, 2008).

Again a thematic emphasis in Standard Operating Procedure was a quest for truth: What and who was behind the horrific photographs of abuse? How much blame rested on the soldiers involved — no one of higher rank than a sergeant? And how much of it could be viewed as “standard military operating procedure?” Did the young soldiers serve as pawns for an upper-level cover-up? The film was yet another example of the complexities involved in understanding the truths surrounding a historical event.

The Unknown Known (2013)

Many could have seen Morris’ interview with former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld as a companion piece to The Fog of War. But Morris said, “No way! The two men are as unalike as two men can be.” The Unknown Known title came from Rumsfeld’s seemingly defensive statement at the beginning of the documentary. He stated that a mission of the Department of Defense is to evaluate “unknown knowns” or “the things you think you know, that it turns out you did not.”

In the 105-minute film, extracted from 33 hours of interviews over 11 filming sessions, Morris sets about querying 81-year-old Rumsfeld about statements made in Pentagon memos while he was defense secretary. Of particular note are the infamous remarks assigning weapons of mass destruction to Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime. Rumsfeld’s feisty responses to Morris’ questions are dismissive, and even when challenged, Rumsfeld refuses to yield any ground. In effect, Morris allowed Rumsfeld to control the interviews to his unrepentant ends. The New Yorker critic David Denby summed up the essence of the exchanges: “If Morris doesn’t quite nail Rumsfeld, his questions lead the Secretary to nail himself. You watch him obfuscate, fudge the issue of torture, smirk about George H.W. Bush (whom he doesn’t like), and offer dull commonplaces when impassioned clarity is called for.” (“Field Maneuvers,” April 21, 2014.) Again, Morris used the Interrotron device for direct eye-to-camera contact with Rumsfeld and to capture closeup facial nuances.

Wormwood, Chapter #1 “Suicide Revealed”

Morris’ most recent documentary begins with a tight shot of New York City’s Statler Hotel, Room #1018A. The camera follows noir-lit images of a man on the telephone — Frank Olson — as he bids his wife goodnight. Then he sits on the edge of his bed reading The Book of Revelation. He reflects on a biblical passage that describes a star called Wormwood, which fell from heaven and embittered the waters that consumed it. (“Many men died of the waters.”) Another man in the room moves to the door and surveys the hotel’s exterior corridor before we cut back to a figure crashing through the window and falling to his death in a lengthy, slow-motion shot. The opening credits roll as Perry Como sings, “No other love have I . . .” The lyrics key the appearance of a 60-ish Eric Olson, Frank Olson’s son.

Eric recounts being awakened as a young child to hear that his father has died in an accidental fall from a New York hotel room. “I was completely paralyzed,” he says to Morris’ cameras in a room void of domestic embellishment. Only a clock hangs behind Eric, its hands frozen between 2:30 and 2:35, signaling the approximate time of Frank Olson’s early-morning death in November 1953. Eric says his beloved father “just disappeared . . . no one ever saw him again.” Thus begins a life-long, all-consuming obsession to discover the truth behind his father’s mysterious death.

Factual details: Frank Olson worked as a civilian scientist for the Fort Detrick Special Operations Division outside Frederick, Md. In 1975, 22 years after Frank Olson’s death, the family received an invitation to visit President Gerald Ford at the White House. Ford offered an apology and monetary compensation to the family. He disclosed that Olson had unknowingly been given LSD in an experiment gone wrong. The cause of death was changed from “accident” to “suicide.”

Wormwood: A review

My review is based on a viewing experience that resulted in 12 pages of legal-pad notes. This documentary series is a darkly woven, complex tapestry of informational bits and pieces, fueled by Eric Olson’s accounts of his six-decade struggle to learn the truth behind his father’s death.

From beginning to end Eric comes across as articulate, driven, smart. In the 1970s he earned a PhD in psychology at Harvard. While a student, Olson began to experiment with a “photo collage” method of investigating the many possible motives/people behind what went on in Room 1018A the night of Frank Olson’s death. Eric refers metaphorically to the room as “an echo chamber of my life.” Backed up by his collage images, Eric rents the hotel room for a week and comes away wondering how anyone could commit suicide by crashing through the room’s two-paned window.

It is possible to argue that Morris’ development strategy in Wormwood resembles cinematic collage. Shots in interview segments with Eric rarely last more than 15 seconds before flipping to another camera angle, even as the voice commentary remains continuous. Morris’ cinematic tailoring is stylistically compatible with Eric Olson’s nervous-energy persona and drive. The director interweaves the interview segments with photo and film montages of 1950s events and people: the Rosenbergs, Vietnam, Korean soldiers recanting earlier claims of brainwashing and chemical warfare, 8mm home movies of the Olson family before Frank’s death. Archival footage includes 1975 Congressional hearings with Olson family members, the exhuming of Frank Olson’s coffin for an autopsy, news footage of various C.I.A figures, and Walter Cronkite reporting on accounts of “germ warfare.” News had begun to surface in the 1970s about the C.I.A.’s secretive MK-Ultra experiments in which mind-altering drugs were given to unsuspecting people.

All of this documentary material resides alongside dozens of imagined reconstructions. We see Frank Olson, portrayed by Peter Sarsgaard, Olson’s wife, played by Hilary Gardner, and various characters associated with him at Fort Detrick or who may have been assigned to his “case”after his death. Reenactments include events in the hotel room, the hotel bar/music lounge, a secret gathering with Frank Olson present at a lakeside cottage, and sessions with a New York therapist where Olson receives treatment for anxiety. In the manner of The Thin Blue Line, the reenactments are dark and shadowy obfuscations of factionalized possibilities about Olson’s death. As Wormwood progresses through its six chapters, Morris revisits events, altering critical details from previous reenactments.

As in his previous films, Morris remains a “silent” interviewer until the final chapter when he’s quietly heard asking Eric Olson, “Do you feel that you could ever let this go?” To which Eric responds: “I have let it go, but it won’t let me go.”

On the whole

One needs to see Wormwood in its entirely to experience its many approaches to investigative filmmaking and its sub-layers of context. For instance, Eric frequently relates his father’s death and his own reactions to Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Periodically, Morris intercuts shots from the film version with Laurence Olivier — one in which tears stream down Olivier’s face. Eric Olson quotes familiar lines from the drama, linking its “murder most foul” to his own tragic saga.

Visually, Wormwood is an unusually dynamic film. Eye-level camera positioning in interviews will abruptly change to high-angle, bird’s-eye views; profile shots of Eric flip back and forth from screen-left to screen-right framing; multi-images appear in a single frame, some the size of postage stamps. A recurring visual technique places archival material (e.g., a speech by C.I.A. director William Colby) in a full-presence position on the left half of the frame while the same material is seen simultaneously on a small TV set in the middle of screen right. Wormwood is very much an optically laden film that demands an occasional rest for the eyes.

Wormwood is different from any documentary I’ve experienced. It’s a masterful example of the power that can come with mixing facts with artful reenactments. And most notably, it’s Errol Morris again demonstrating his gift for allowing his subjects to reveal themselves: quirky pet owners; the citizens of Vernon, Florida; the MPs who served at Abu Ghraib; Robert McNamara; Donald Rumsfeld; and now, none more memorably than Eric Olson. Wormwood is a film I’ll long remember and think about.

Reginald Franklin - 1986...MA in Telecommunication Arts

Frank…so nice to see you are still doing your thing…Hope all is well with you…I’ve run into Mary Ann at BEA a couple of times, but haven’t made it back to Ann Arbor in quite some time…I’ve been teaching video and film production for the last 27 years…thanks to you and Dr. Watson…Take care Sir…my email is franklinr@savannahstate.edu

Reply