Modeling

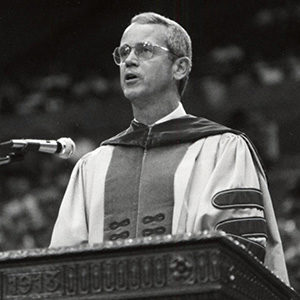

“Model MIT president” and former U-M Provost and COE Dean Charles Vest (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

There stands in front of me a carpenter’s model of a bureau—16 inches high and fashioned out of oak. It’s early 19th century, or perhaps late 18th century, with five small drawers and miniature metal pulls for each of them, so they slide easily open. This piece of furniture is English, or possibly American, and built in the “plain style.” The top two rows have two drawers apiece, the third and bottom row contains a single drawer: seven inches wide. The joints are dadoed, the four feet carved to simulate a lion’s clawed feet, each at a slight angle, facing out. The whole has been stained a light brown.

Now time has darkened it, so the brown is deeper on the surface of the bureau than on the wood of the drawers’ interior, which only intermittently has been exposed to air. The bureau, it appears, was constructed for two purposes. First, it served as a model for the apprentice cabinet-maker who would copy it assiduously until a full-size version might be attempted, then built. And, second, it would furnish a sample for a customer or a potential purchaser elsewhere, so the carpenter while traveling could display his wares. (In similar fashion, an itinerant luthier might carry a box of miniature violins to demonstrate his excellence; these violons de poche would engender a commission for a full-sized instrument built on order back at the shop.) This doubled usage—both a model and display — seems emblematic of what a successful period of training can achieve: a student works in miniature, then builds the actual thing.

I once heard the late Charles Vest described as a “model president” at the Massachusetts of Technology. Before his lengthy presidency at M.I.T. (1990-2004), “Chuck” had served as dean of U-M’s College of Engineering and then as our University provost. We were friends, and when I complimented him on the praise, he told me, with characteristic wit as well as modesty, that he had indeed been proud of the term, “model,” until he looked up its dictionary definition: “a small-scale version of the real.” In his case, however, a secondary meaning — “ideal, exemplary” — held true.

“A line will take us hours maybe”

All teacher-editors know that one can turn and turn the pages of apprentice-work, stifling boredom, finding nothing new, and then encounter a sentence, a paragraph, a scene that’s notable. These hot spots in a narrative are hard to predict but impossible to miss; it’s when an action or description or a speech or a character takes wing. This is, I think, as true of poetry as prose. In “Adam’s Curse,” William Butler Yeats declares:

A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

That word “naught” may take some discussing. It’s an Anglicism, more current in England (or, in Yeats’s case, Ireland) than America, where we might say “nothing” or “zero” or “zip.” But after the two gerunds — “stitching and unstitching” — the finality of “naught” feels apt; a monosyllabic negation undoes what went before. Imagine, further, how different the tone of the “thought” would be if the poet had written “perhaps” or “possibly” or “mayhap” or even “peradventure” instead of his preferred and colloquial “maybe.” The voice is conversational; then comes the formal “naught.” It might have taken hours to come upon that closure, or the rhyming couplet (“thought” and “naught”) might have come to him immediately; we readers cannot know. Which demonstrates his point

In fact, we do have some idea since Yeats did keep his manuscripts — though this relatively early poem has only a few drafts preserved in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library. It seems that “naught” was with him from the start, though other changes have been made. At first, for example, he wrote, “A good line will take hours maybe,” then excised the “good” and added “us” to keep the syllabic count intact. Further, it renders the assertion general; he doesn’t use first person singular but the plural “us” and, two lines later, “our.” The second line originated as, “And yet must seem a momentary thought” before Yeats settled on the formulation, “Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,” and the third line read at first, “Or all the stitching and unstichings (sic) naught.”

Vision vs. re-vision

It’s one of the small mysteries of the act of composition that a passage revised 20 times may look as nonchalant or casual-seeming as one that arrives whole cloth. All writers, I believe, recognize that moment when words gather together unbidden, almost as though they were writing themselves and not subject to scrutiny and hesitation and erasure. It’s the difference, in effect, between vision and revision — but the final product can look, to the reader, the same. “A moment’s thought,” as Yeats asserts, may well be the result of hours and hours of work, but it might also be just what he claims: a moment’s thought. The trick is to know when a phrase needs rephrasing, when it feels inexact or stilted or somehow misses the mark. And then to revise and revise.

So the work can be “inspired” and composed at a white heat. Or it can have been rewritten 20 times. Or it may have been rewritten 20 times. Or it may be rewritten 20 times. Or it can be composed a score of times. Quite often the young writer (or the old and weary one) at the end of the third or the 12th revision, will say, “To hell with it; this is as good as I can do.” But that’s a decision taken out of inattention or exhaustion or poor judgment, the automatic pilot nodding at the wheel. To “leave well enough alone” may be a successful moral strategy; in the realm of aesthetics, however, it’s a position of weakness, not strength. Excellence, it would appear, inhabits the first draft or the 21st; mediocrity resides between. To “model” is to copy until the imitation becomes, after long practice, real.