A very, very, very fine house

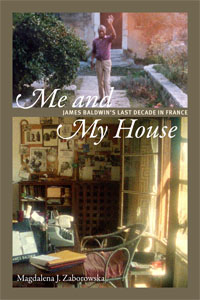

My colleague, Magdalena Zaborowska, has just published a book on James Baldwin. Its title tells the story: Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France.

My colleague, Magdalena Zaborowska, has just published a book on James Baldwin. Its title tells the story: Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France.

A professor of Afroamerican and American studies at U-M, Zaborowska has exhaustively researched and in detail described the “last decade” and domicile of the iconic American author, who spent years as an expatriate. Too, she chronicles her own efforts to visit the house by way of imagining what it signified to the man in exile there — a task made all the more melancholic by the fate of the building itself. The writer’s heirs were unable to keep control of or maintain the property. It fell into the hands of developers, and after a long legal wrangle Baldwin’s home was razed. Now luxury apartments are being constructed where once he worked and slept, and the village of Saint-Paul de Vence — nestled in the foothills of the French Préalpes — has become a tourist trap.

“Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition,” as Baldwin wrote in his eloquent novel, Giovanni’s Room (1945). And Zaborowska does an impressive job of evoking the “aging, lonely, sexually dubious, politically outrageous, unspeakably erratic freak,” as the writer called himself in No Name in the Street (1972). The mas was his haven, his retreat; to my knowledge he slept longer and produced more language under that roof than anywhere else in his wanderer’s life (1924-87). It’s the house in which he died.

Last year the smaller book James Baldwin: Escape from America, Exile in Provence by Jules Farber appeared. Inspired by The Welcome Table, (the title of a work-in-progress during Baldwin’s final period) Farber attempts to recreate a scene he never saw first-hand — quoting from the recollections of, among many others, Nikki Giovanni, Yves Montand, Toni Morrison, and Quincy Troupe. Together, the books bring to life a chapter long since buried, and it’s fine to be reminded of that time and place. My own memory of the “welcome table” is vivid, since more than half my life ago I was James Baldwin’s near-neighbor.

Courting favor

I met “Jimmy” first in 1970 and then again in 1973, when my young wife and I rented a nearby house and visited him often. After a stint as wanderer, Baldwin had settled in Provence, establishing a work pattern and an entourage. He had a chauffeur large enough to double as a bodyguard, a cook, a companion named Philippe who acted as a kind of secretary-manager, and various others whose function is less easy to describe. There would be a dancer or painter in tow — old lovers or associates from some project in the offing, or projected, or long past. They came from Italy, America, Algeria, Tunisia, Finland. Brothers and nephews passed through.

I met “Jimmy” first in 1970 and then again in 1973, when my young wife and I rented a nearby house and visited him often. After a stint as wanderer, Baldwin had settled in Provence, establishing a work pattern and an entourage. He had a chauffeur large enough to double as a bodyguard, a cook, a companion named Philippe who acted as a kind of secretary-manager, and various others whose function is less easy to describe. There would be a dancer or painter in tow — old lovers or associates from some project in the offing, or projected, or long past. They came from Italy, America, Algeria, Tunisia, Finland. Brothers and nephews passed through.

We were rarely less than six at table, and more often 10. The cook and the femme de ménage came and went; the men stayed on. They treated their provider with a fond deference, as if his talent must be sheltered from invasive detail, the rude importunate matters of fact. They answered the phone and the door. They sorted mail. There was an intricate hierarchy of rank, a jockeying for position that evoked nothing so much as a Provencal court — who was in favor, who out; who had known Jimmy longer or better or where; who would do the shopping or join him in Paris for the television interview or help with the book-jacket photo. He was working, again, on a novel: If Beale Street Could Talk.

This crazy face

Much of what I knew of the plight of the black American I had learned from reading him. And what sometimes seemed like paranoia could be argued as flat fact. The deaths of Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., Bobby Kennedy, George Jackson, the named and nameless legion in what he called “the royal fellowship of death,” his own impending 50th birthday, and the sickness of beloved friend and mentor, the painter Beauford Delaney: all weighed heavily that first shared winter. “This face,” he’d say, and frame it with his slender glinting fingers. “Look at this crazy face.”

Much of what I knew of the plight of the black American I had learned from reading him. And what sometimes seemed like paranoia could be argued as flat fact. The deaths of Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., Bobby Kennedy, George Jackson, the named and nameless legion in what he called “the royal fellowship of death,” his own impending 50th birthday, and the sickness of beloved friend and mentor, the painter Beauford Delaney: all weighed heavily that first shared winter. “This face,” he’d say, and frame it with his slender glinting fingers. “Look at this crazy face.”

Baldwin drank scotch. We drank wine. I have not as yet described the quality of kindness in his manner, the affection he expected and expressed. His face is widely known — that dark glare, broad nose, those large protruding eyes, the close-fitting cap of curls then starting to go white. But photographs cannot convey the mobile play of feature, the intensity of utterance, the sense he could contrive to give that attention matters and gesture can count. There was something theatrical in Jimmy’s manner, and it grew automatic at times. He would embark on what seemed a tirade, a high-speed compilation of phrases that clearly had been phrased before, a kind of improvised lecture spun out of previous speech. He stared at you unblinkingly; you could not turn away. He wore expensive jewelry and fingered it, talking. He smoked. He had been holding center stage for years.

“Understand me”

You shifted in your seat. You said, “Yes, but…” and he raised his imperious manicured hand. Dialogue, for Baldwin, was an interrupted monologue; he would yield the platform neither willingly nor long. He could speak incisively on a book he had not read. But again and again he impressed me with his canny ranging, his alert intelligence. “Understand me,” he would say. “It’s important you understand.” And it was important, and in that mesmeric presence you thought you understood . . .

Literary reputation is a roller-coaster ride. For a time James Baldwin’s work was omnipresent and hugely influential in our culture; then he fell out of favor and seemed out of date. Now again, and in part because of last year’s splendid documentary I Am Not Your Negro, he has become the spokesman of his long-suffering race. In a world when third-rate writers everywhere have plaques and rooms and museums established in their honor, it seems doubly wrong and shameful that the house in Provence has been bulldozed, dust to dust. But in Professor Zaborowska’s welcome book, the man and his beloved residence live on.

Melba Boyd - 1979, Doctor of Arts, English

Prof. Zaborowska’s work on Baldwin is moving and amazing. Her insight into Baldwin’s life and words are beautifully crafted. It is a great contribution to Baldwin’s legacy.

Reply