Don’t ask the doc

Only about a third of U.S. medical schools require the minimum 25-hour nutrition curriculum recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.

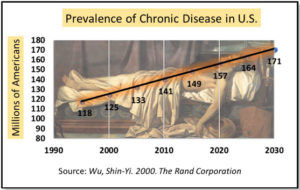

As I have pointed out in many past issues of Health Yourself, research consistently points to a link between an individual’s nutritional status and chronic disease. The growing list of diet-related diseases and a burgeoning obesity epidemic prove diet regulation is the most important element in the treatment of most lifestyle-induced chronic diseases. In many cases, if diet were skillfully addressed, it could comprise a patient’s entire treatment.

While we know the importance of diet for enhancing overall health, our physicians and health-care providers — the very people most responsible for the direct treatment of disease — lack the adequate education to provide current, science-based nutrition advice to their patients, or even themselves.

In 1895, the famous medical educator W.G. Thompson complained about the lack of nutrition education in his medical textbooks on nutrition. “The subject of the dietetic treatment of disease has not received the attention in the medical literature which it deserves,” he wrote, “and it is to be regretted that in the curriculum of medical colleges it is either wholly neglected or disposed of in one or two brief lectures at the end of a course in general therapeutics.” (Thompson, W.G., 1895 Practical Dietetics with Special Reference to Diet in Disease, D. Appleton & Co., Publ.)

Thompson surely would be dismayed to know that we continue to face a striking absence of funding for nutritional intervention research to study, in a comprehensive manner, the relationship between the foods we consume and the chronic diseases we develop.

Thompson surely would be dismayed to know that we continue to face a striking absence of funding for nutritional intervention research to study, in a comprehensive manner, the relationship between the foods we consume and the chronic diseases we develop.

On the one hand, we see an increase in preventable nutrition-related diseases (e.g., obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease). On the other hand, we have “Internet pseudo-experts” and “quasi-self-prepared” charlatans promoting opinion as fact, guidelines that are moving targets, and a public that relies on nutritional supplements and self-diagnosed remedies as magic cures.

Some seven out of 10 deaths among Americans each year are the result of chronic diseases that could be prevented with proper lifestyle intervention. This fact underscores the need for increased nutrition education among our medical professionals.

Status of nutrition education in U.S. medical schools

Reports between 1979-84 indicate that less than 30 percent of all medical schools required even one course in nutrition. Surely this inadequate state of affairs would improve as nutrition research became more ubiquitous? Well, a follow-up study of all U.S. medical schools in 2004 found no increase in nutrition education. Only 32 schools (30 percent) required medical students to take a separate nutrition course. On average, medical students received between 1-20 contact hours of nutrition instruction out of literally thousands of pre-clinical education hours. Disappointingly, only 40 of the 126 U.S. medical schools required the minimum 25-hour curriculum recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.

The most recent national survey in 2010 of nutrition education in U.S. medical schools is not encouraging. Only about 26 medical schools, just 25 percent of the total (down from 30 percent in 2006), required a dedicated nutrition course. Overall, on average, medical students received just 19.6 contact hours of nutrition instruction during their medical school careers (range: 0-70 hours). And, only 27 percent of all schools met the minimum 25 required hours set by the National Academy of Sciences. It is tough to know how individual schools rank; the researchers at the University of North Carolina who produced the study will not release data on specific programs.

Surveys of nutrition education in Western European medical schools reveal slightly better results; estimates suggest about 69 percent of schools required, on average, 24 hours of nutrition education.

Lack of nutrition

One of the most disturbing aspects of the lack of nutrition training for physicians is the finding that many medical school faculties do not believe more nutrition knowledge is necessary. In 2004, about 88 percent of U.S. medical school faculty thought they needed to include more nutrition education; in 2009 that figure dropped to 79 percent. With the growing demand for greater specialization and supporting education, I would not be surprised that in today’s academic environment even fewer medical school faculty feel more basic nutrition education can be added to an already packed medical school curriculum.

With such poor training in nutrition, it should not be surprising that doctors know less then they think they know about the subject. Of course, most people don’t challenge their health professionals regarding their expertise in nutrition and lifestyle intervention. That would be awkward, right? Well, I’ve done it. And with few exceptions, I’ve been shocked, disappointed, and dismayed.

Actual versus perceived expertise

Based on several studies that tested medical professionals’ knowledge of nutrition and lifestyle change (including physicians in many disciplines), there is an undeniable misalignment of actual and perceived nutrition and lifestyle-modification knowledge, mainly related to diet and exercise. Doctors say they are knowledgeable about nutrition and chronic disease management. However, research shows the majority are getting failing grades in this important area. Test results indicate misinformation and misconceptions regarding lifestyle/nutrition knowledge is endemic among physicians and other medical professionals.

According to a review published in 2010 “virtually every published study about physicians and nutrition counseling showed that primary care physicians … were not delivering nutrition services to their patients.” Another study recorded thousands of patient visits to more than 150 physicians and measured how much nutrition advice was offered. It could not have been very much; the average time per visit was less than 10 seconds!

Summary

I believe all of us need to become more responsible for managing our physical and mental health – hence the name of this column, Health Yourself. Educating yourself about the role nutrition and physical activity play in lifestyle management is top of the list.

Become a self-advocate. Ask your health professional about his/her nutrition and lifestyle management training and check for advanced continuing-education credentials. Don’t be afraid to ask for referrals for health professionals who are qualified to provide nutrition counseling, advice, or evaluation of your current status.

One encouraging trend is that medical professionals are beginning to integrate patient nutrition/lifestyle management into their practices. Some medical practices now include a board-certified dietitian/nutritionist; others include experts educated and trained in lifestyle management.

References

- Adams, K.M., et al. ”Nutrition in medicine: Nutrition education for medical students and residents.” Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 2010; 25(5):471.

- Adams, K.M., et al. “Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools: Latest update of a national survey.” Academic Medicine, 2010; 85(9):1537.

- Adams, K.M., et al. “Status of nutrition education in medical schools.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2006; 83(4):941S.

- Aspry, K.E., et al. “American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; and Stroke Council. Medical Nutrition Education, Training, and Competencies to Advance Guideline-Based Diet Counseling by Physicians: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association.” Circulation, 2018 Jun 5; 137(23).

- Chen, P.W. “Teaching doctors about nutrition and diet.” The New York Times

- Chung, M., et al. “Nutrition education in European medical schools: Results of an international survey.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2014; 68(7):844.

- Daley, B.J., et al. A.S.P.E.N. Task Force on Postgraduate Medical Education. “Current status of nutrition training in graduate medical education from a survey of residency program directors: A formal nutrition education course is necessary.” The Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 2016; 40(1):95.

- Delegge, M.H., et al. “Specialty residency training in medical nutrition education: History and proposal for improvement.” The Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 2010;34 (6 Suppl):47S-56S.

- www.nutritionfacts.org/video/medical-school-nutrition-education/

- Kelly, C.J. “Invigorating the context and content of nutrition in medical education.” Academic Medicine, 2011; 86(11):1340.

- Khandelwal, S., et al. “Nutrition education in internal medicine residency programs and predictors of residents’ dietary counseling practices.” Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 2018; 5:238.

- Kolasa, K.M., et al. “Barriers to providing nutrition counseling cited by physicians: A survey of primary care practitioners.” Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 2010; 25(5):502.

- National Academy of Sciences. 1985. “Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools.”

- Parker, W.A., et al. “They think they know but do they? Misalignment of perceptions of lifestyle modification knowledge among health professionals.” Public Health Nutrition, 2011; 14(8):1438.

- Stange, K.C., et al. “Illuminating the ‘black box’. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians.” The Journey of Family Practice, 1998; 46(5):377.

- Thompson, W.G. “Practical Dietetics with Special Reference to Diet in Disease.” (1895, D. Appleton & Co., Publ.)

Anthony J Parisi - 1981

Thank you for this article. I fully support that U.S. medical schools should increase the amount and quality of nutrition courses that medical students should be required to take.

Reply

Linda Kervin - 1967

Maiden name is McAllister

Interested in diet and disturbed by obesity in our country. Glad to hear obesity prevention is being discussed at Michigan.

Reply

Nancy Downie - J.D. 1990

Good for you for publishing this article! My husband (Michigan B.A. 1969) and I adopted a whole foods, plant-based diet after watching the documentary “Forks Over Knives” 6 years ago. The movie presents compelling evidence for the causal relationship between the standard American diet and heart disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity and other conditions that are rampant in this country. Drs. Caldwell Esselstyn, Jr., and T. Colin Campbell, who are featured in the movie, can hardly be called “Internet pseudo-experts” or “quasi self-prepared charlatans”. They are responsible, mainstream physicians who have had the courage to speak out on this issue. I volunteer at a hospital, and I am appalled by much of the food that I see on the trays of patients in the cardiovascular and oncology units. The world also needs to move towards plant-based eating for environmental reasons. Thank you for encouraging medical schools to address these concerns.

Reply

Mary Niester - 1999

Referring patients to a Registered Dietitian/Nutritionist is the best way to go. These individuals have extensive education from accredited programs and have the research to back up the benefits they bring to the public and other healthcare providers. They spend anywhere from 30 to 60 minutes with a person properly screening, assessing and counseling individuals. To learn more visit the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics http://www.eatright.org (or nutrition experts at U of M’s School of Public Health and Health System.

Reply

Julianne Jeffries - MBA 1999

I have a certification in Plant-based nutrition and could not agree more completely with this article. However, just sending people off to Nutritionists is not always the answer, either. Many nutritionists are still not well versed in WFPB (Whole Foods, plant-based) nutrition and the need to eat non-processed, NO SUGARS and whole, clean foods. I cured what the world’s leading experts said was incurable, only using food. I was legally blind in one eye after the discovery of a rare, inoperable tumor that is wrapped around my optic nerve. My own experience and research lead me to be WFPB and I now have 20/20 vision even though the tumor still co-exists on my optic nerve. It is about reducing inflammation and allowing your body to work optimally. I currently coach people on how to improve their diets and am thrilled when people say “wow! Your food is amazing!”

Reply