Eschewing artifice

Alfonso Cuarón (Image credit: Gage Skidmore.)

In collecting my thoughts on the masterful artistry and powerful appeal of Alfonso Cuarón’s “memory-inspired” Roma, I was drawn back to the 1950s/’60s films of French “new-wave” director Robert Bresson and the Italian neo-realist Roberto Rossellini. These iconic filmmakers broke from traditional approaches to cinematic expression, eschewing artifice, avoiding the well-made plot narrative, casting unknown actors, filming them in real locations, and downplaying production values for mise-en-scene simplicity. Most importantly they used these approaches to tell stories that drew on the realities of life.

Cahiers du Cinema co-founder André Bazin brilliantly detailed the transformative impact of Bresson, Rossellini, and other filmmakers of similar inclination in a collection of contemporaneous essays. Hugh Gray translated and published the essays in two volumes by the University of California Press. What is Cinema?(1967) and What is Cinema? Volume II (1971) serve as indispensable theoretical works for the study and evaluation of film art.

Bazin said of Bresson’s simple, dark study of a lonely isolated French cleric: “The Diary of a Country Priest (1951) impressed us as a masterpiece, and this with an almost physical impact, if it moves the critic and the uncritical alike, it is primarily because of the power to stir the emotions rather than the intelligence, at their highest level of sensitivity …The succession of events is not constructed according to the usual laws of dramaturgy under which the passions work toward a soul-satisfying climax. Events do indeed follow one another according to a necessary order, yet within a framework of accidental happenings. Free acts and coincidences are interwoven. Each moment in the film, each setup, has its own due measure – alike — of freedom and necessity. They all move in the same direction but separately like iron filings drawn to the overall surface of a magnet.” (What is Cinema?, 1967, p. 134.)

In praise of Bresson at the time of his death in 1999 the late film critic Roger Ebert wrote: “Because the actors didn’t act out the emotions, the audience could internalize them … What you noticed was the extreme restraint of the actors, and the way the action centered on what his characters saw rather than what they did.” (Chicago Sun-Times, Dec. 23, 1999.)

Similarly, Bazin praised Rossellini for his films of stripped-down simplicity (Paisan, 1946, Travel to Italy, 1954). “To have a regard for reality does not mean that what one does is in fact to pile up appearances. On the contrary, it means that one strips the appearance of all that is not essential, in order to get at the totality of its simplicity. The art of Rossellini is ‘linear and melodic.’” (What is Cinema?, Volume II, p. 101.)

A compelling exercise in observation

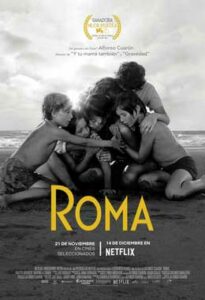

(Netflix.)

Although Roma is neither new-wavish nor neo-realistic, in re-examining Bazin’s theoretical essays about transformational cinema I was struck by how closely his ideas aligned with how I experienced Roma’s artistry and its impact. First, Cuarón’s Roma is a compelling exercise in observation — of seeing — rendered with minimal editing and without traditional dramaturgical tailoring. It’s the filmgoer’s privileged access to sustained points of view in scene after scene that imbues Roma with its visual power.

Roma’s script was born of Cuarón’s childhood memories as a 10-year-old boy living with his single-mother family in the Mexico City suburb called Roma. In focusing on the family’s beloved domestic worker and nanny, Cleo, (Yalitza Aparicio, a novice movie actor), Cuarón masterfully allows the succession of events centered on his protagonist to shape a film of intimacy, mood, shade, and often unspoken feeling — at once captivating.

The film’s sequential opening initiates this approach. As titles roll, Cleo scrubs a tiled entranceway (photographed with visual and aural appeal), tidying up the family’s bedrooms, gliding down the stairs with the day’s laundry, and then rushing off to pick up young Pepe after school. The shifts from location to location are realized with smooth, barely perceptible camera pans. Cuarón chose to serve as his own cinematographer and, in addition to his writing and directing, carries out the job with unified precision. The camera’s revelation of Cleo’s place and domestic role in the household is made incontrovertibly clear, simply conveyed not with dialogue or editing emphasis, but rather with the visual display of real-time and “accidental” action. This, I believe, fits Bazin’s praise of filming that is “linear and melodic.” Indeed the opening flow of scenes in Roma has a balletic feel.

A natural

To capture and enhance the film’s natural affect, Cuarón shot the scenes from his script in the exact chronological order in which they would appear in the finished film. The actors, chosen after an eight-month-long search through Mexico’s provinces, received dialogue and blocking instruction each morning before that day’s shoot. Although at first a bit chaotic, the approach worked. When a nervous Aparicio told Cuarón that she didn’t know how to act, the director assured her, “That’s okay. When we’re done filming, I’ll teach you how.” He didn’t have to. She embodied Cleo brilliantly.

Cleo’s strong and largely silent presence is key to Roma’s many perfectly realized scenes. I cite five: Antonio’s (Fernando Greiago) abandonment of his family on an outside street, wife Sofia (Marina de Tavira) trying to hold him back with a long embrace as Cleo looks on; a heartbreaking movie date with Fermin (Jorge Antonio Guerrero) in which Cleo announces “I’m late”; the soaring drama in a hospital surgery room; and two wrenching scenes at a Mexican beach resort — one involving a monumental display of commitment by Cleo to her “family.”In each of these key scenes, Cuarón employs an in-depth compositional technique where Cleo is foregrounded close to the camera for immediacy and impact. This blocking is especially evident in the hospital surgery room where Cleo is set to deliver her baby. Seen lying on the operating table in the immediate foreground Cleo watches as the pediatrician “prepares” her baby on a background table. The action is eerily displayed in soft-focus imagery and creates a traumatic and devastating scene.

Soundscape

Yalitza Aparicio makes her acting debut in the film. (Netflix.)

Here, it’s necessary to note the brilliant soundtrack that resonates from the beginning to end of Roma. The film doesn’t have a true score — just incidental car radio music and in-the-scene incidental music. But pick any scene and you’ll hear the inextricable relationship of sound to image: the swoosh of water that emerges as Cleo’s unseen garden hose douses the entranceway’s tiled flooring — the sound moving in and then reversing backward until the water finally drifts into a drain pipe; the haunting announcements of a potato vendor passing by the family home on his daily route; silence interrupted by Cleo quietly singing a melody to herself as she works; the family dog, Borras, at the entrance gate, endlessly leaping and barking in anticipation of returning family members; the loud overlapping dialogue and sounds in the operating room, which make the drama all the more chaotic and psychologically unnerving; and who can soon forget the power of sound in the climactic beach scene, the ocean roaring like an angry monster around the action? Each sound cue adds realism, atmosphere, dramatic emphasis, mood, nuance, and time-relevant evocations, and Roma displays the art of sound-mixing at its most advanced and compelling. Two of the film’s 10 Oscar nominations aere for Best Sound Mixing and Best Sound Editing.

Roma doesn’t shy away from Mexico’s political situation in the early 1970s. In the film’s most expansive and documentary-like parts, Cuarón recreates the 1971 Corpus Christi street massacre with epic realism. Viewed by Cleo from a furniture store window above, the street battle between government activists and student demonstrators plays out in a furious display of gunfire. Suddenly in the midst of the fighting, Cleo’s ex-boyfriend Fermin appears in the furniture showroom to “take out” fleeing opponents. Cuarón foreshadows Fermin’s role in the confrontation when Cleo visits a massive and intense martial arts training session in an open field outside Mexico City. On a hill in the background are the large letters “LEA,” a reference to Mexico’s president at the time, Luis Echeverría Álvarez. Álvarez was a political affiliate of the Institutional Revolutionary Party whose policies set the rural poor against the wealthy. Fermin’s commitment to the cause had earlier been displayed for Cleo in a rousing, naked martial arts demonstration inside a rented rendezvous room.

Brush strokes

Novice actress Yalitza Aparicioricio stars as Cleo. (Netflix.)

It follows that any film built around a 10-year-old boy’s childhood memories would incorporate random and “great-small-moment” brush strokes to fill out the larger picture. One of these random occurrences is charmingly Fellini-esque in the way that films like Amarcord (I Remember) included events that were ambiguously fantastic. In a New Year’s Eve scene at “Uncle’s” country estate, we see Cleo, Sofia, and her children (Tono, Paco, Sofi, and Pepe) enjoying the celebration. Suddenly a boogie man, dressed in gorilla garb, arrives to frighten the children and lead the partygoers in dancing before the Christmas tree. Outside a sudden unexplained fire is announced, and the adults and children frantically rush to douse the patches of fire. A cut is made to the boogie man who appears, unmasked, in a foreground shot, singing a plaintive song.

Happier scenes reveal Cleo as very much at ease in her life: racing to a local taco shop with cook Adela (Nancy García García, ), huddling among the family watching a Mexican sitcom, Paco’s arm draped around Cleo’s shoulder; playing “dead” with Pepe, the two lying on their backs, head to head — a brief respite for Cleo from the chores of the daily laundry. Pepe, the youngest of the three sons, is preternaturally charming in his imaginative tales of life before he was born: “I was a pilot back then,” “I was a sailor and I drowned in a storm.” There are the farcical moments when Sofia struggles to drive their too-large car through the gate and into the narrow entrance passageway, perpetually spattered with Borras’ excrement. And too there is a lovely re-evocation of Grandmom Teresa (Verónica García), a gentle, but strong and soothing figure in a household characterized by disruption.

Cuarón’s tribute to the women in his life, as he terms it, is a paean from the heart — an immersive, detailed look at a distant time when a boy’s world seems broken and everyday life upended. Yet, even amid the despair, there’s also a bonding and connectedness that glances toward the future. Although it is by intention periodic in its chronological flow, by film’s end it’s worked its artful magic to give the filmgoer the feeling of having experienced the characters’ lives.

To apply Roma to André Bazin’s theoretical musings about Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest: “Events do indeed follow one another according to a necessary order, yet within a framework of accidental happenings. Free acts and coincidences are interwoven. Each moment in the film, each set-up, has its own due measure — alike — of freedom and necessity. They all move in the same direction but separately like iron filings drawn to the overall surface of a magnet.”

Roma worked that magnetic spell for me; it’s one of the most beautiful and emotionally stirring movies I’ve ever seen.

Minh Tu - 1979

Roma touched me personally as I lived in a similar household in Vietnam. When I was older, I realized how much loyal and loving my nanny was. She left us when her only son died in the war. Roma also captured perfectly the pretense of the upper class to keep up with the Joneses.

Reply

William Connolly - 1951 AB (Economics); 1952 AM (English)

This essay, unlike that of many film “critics” and much like “Roma” itself, is a perfect model of clarity. Reading it helped me to understand WHY I admired the film. Prof. Beaver has enhanced by appreciation of Cauron’s work. Thank you.

Reply

Tina Tolin - 1970 AM

I too was taken in by Roma. Today, I saw Shoplifters and would recommend it to people who enjoy this style of film. I would love to know what Frank Beaver thinks of the comparison. Thank you for your wonderful columns.

Reply

Frank Beaver - Professor Emeritus

Thank you, Tina. Your comment has inspired me to write my next column on SHOPLIFTERS and the other four Oscar nominees for Best Foreign Language Film. In my opinion, it’s the toughest category for this year’s Academy voters, and although some may not have been seen by Oscar night, each deserves to be called out for consideration. Frank Beaver

Reply

Tina Tolin - 1970 AM

Perfect, can’t wait!

Reply