Stealing scenes

(Quill Driver Books, 2019)

The bookshelf labeled “Scriptwriting Guides by U-M Professors and Alumni” just got a little more crowded with the addition of Jim Mercurio’s The Craft of Scene Writing: Beat by Beat to a Better Script (Quill Driver Books, 2019).

It joins an impressive collection of must-have titles that began in 1939 with English Professor Kenneth Thorpe Rowe’s Write That Play. Rowe’s text soon became the standard for creative writing instructors and their students. A colleague of mine at the University of North Carolina, novelist Ralph Dennis, gave me the copy of Write That Play that had been the required text in John Gassner’s playwriting class when he was a doctoral student at Yale. Dennis knew I was heading to Ann Arbor to work on my doctorate at the time.

“Study with the master himself,” he told me. Professor Rowe was in his last decade teaching dramatic playwriting at Michigan. Twelve lucky students secured seats in his fall 1967 evening course in Mason Hall. One of them was future director/screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan.

(Regan Books, 1997)

Robert McKee, MA ’72, screenwriting lecturer and script consultant, also studied with Rowe. While teaching at the University of Southern California in the mid-’80s, McKee began offering his commercial “Story Seminar,” a three-day lecture series. Later, he developed “Genre,” a one-day seminar focused on the unique characteristics of romance, horror, comedy, noir, etc. McKee continues to teach the popular programs around the world. In 1997, a book version of the seminars appeared as Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and Principles of Screenwriting (HarperCollins); it’s available as an e-book today.

Authors of scriptwriting guides generally maintain it’s not just a compelling story that makes an effective play or screen drama but the methods used in creating them. In other words, it all comes down to craftsmanship. Thus, Rowe’s Write That Play employed a strategy of deconstructing classic one-act and full-length theater works: A Night At An Inn, Riders to the Sea, and A Doll’s House, among others. Using these examples, writing students worked through the key components Rowe considered essential in “building” a play: finding the dramatic material, shaping structure and form, developing characters, and writing dialogue throughout the first draft and subsequent revisions. McKee’s Story guidelines follow similar creative writing components.

That’s my scene

Now just off the press is Mercurio’s unique and remarkable guide to scene — not screen — writing. A writer, feature film director, and “script doctor,” Mercurio has been an executive consultant on numerous screenplays. He also is a popular screenwriting lecturer. He culls hundreds of scenes from feature motion pictures and offers analyses of the numerous ways a writer can produce a better script. The book presents a clear, concise, and invaluable shortcut to scene writing craftsmanship. In the following Q&A, Mercurio explains why he got into the “how to” game.

Frank Beaver: Jim, I found your book The Craft of Scene Writing to be a much needed addition to existing craft guides that are meant to inspire better creative storytelling for film and television screens.

What inspired you to undertake this project?

(Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1939)

J.M.: While I was making small movies in Hollywood and writing, I would teach screenwriting and write about the craft. It was a way for me to stay in touch with my love of movies. I miss the days in Ann Arbor where, in a 36-hour period between the MLB and the Michigan Theater, I might be able to see a 70mm print of Apocalypse Now along with theatrical showings of Blue Velvet, Umberto D, Persona, and Star Wars while grading papers on Animal House.

I knew I had a screenwriting book in me, but I wanted to figure out a take that was special and unique. My experience as a filmmaker meant that I paid attention to more in a movie or given scene than just the writing. In the last film I directed, I sat through several hundred audition performances for the same scene in a week. I am not sure why it took me so long to figure out this angle. I don’t think there has been a screenwriting book that focuses solely on scenes.

FB: How would you say The Craft of Scene Writing differs from other writing guides, say Syd Field’s Screenplay, long considered a classic?

JM: Assuming a writer has a great idea for a concept and story, my book helps them execute their ideas so their story is well-told. Yes, it’s about art, creativity, and finding your voice. But on a practical level, if a writer can deliver a script that doesn’t need “development” — energy and resources to improve it — it is ready to attract agents and managers … and eventually actors, which gives it a better chance to be produced.

Most of the canonical screenwriting instruction focuses on structure and story. Even Lajos Egri’s The Art of Dramatic Writing looks at how character and conflict are the driving force in dramatic construction. By focusing on scene writing, my book sets itself apart. It focuses on a different set of tools.However, it’s not some new trendy approach. Scene writing is storytelling in its purest form.

F.B. In laying out your premises for better scene writing you maintain that a scene contains an inherent story, and the nature of that scene story comes through a series of zigzagging beats. Explain.

The smallest unit of storytelling is a beat. It’s a small action that characters take to achieve their goals. Ultimately, a scene is a series of beats that zig and zag and escalate to a climax, surprise, or reversal. A story is the same thing, but the broader beats usually involve higher stakes. A beat in a scene might be a character’s attempt to get another character’s phone number with the bigger goal of getting to go on a date: Boy gets girl. In that same romantic comedy, a broader beat and turning point for the story might be the twist at the end of the second act: Boy loses girl.

F.B.: Which leads to your analogy that “Structuring beats in a scene is likened to a nesting doll.”

J.M.: Yes, it’s a reminder that a scene is a story in and of itself.

If you were to graphically track the ups and downs of a scene, they would look like the ups and downs of a sequence, an act, and a story. Scenes are embedded into sequences. Sequences into acts. Acts into a story.

FB: You discuss the principle and importance of story density in creative writing. Please comment.

J.M.: I invented that phrase as a clever way to capture the notion of “all the good stuff that can be in a scene” given its length. For the most part, the more the better. You don’t want a five-page scene to tackle one relatively unimportant dramatic question. If writers want to tackle long or more ambitious scenes, the book shows them the variety of storytelling tools at their disposal.

F.B.: This seems to relate to your notion that there is a difference between writing short scenes and longer ones.

Aaron Sorkin has made a career writing snappy dialogue, often spoken while the characters are walking — fast. (Wikipedia.)

J.M.: If Aaron Sorkin, Larry Kasdan, or Tony Gilroy write a long scene it will do what it’s supposed to do. However, amateur writers are sometimes enamored by the long scenes that writers and filmmakers like Woody Allen, Quentin Tarantino, or even Fellini might pull off. Too often, they will write an eight-page scene that contains only enough story and other “good stuff” to sustain a three-page scene. “Story density” gives writers an intuitive way to assess if there is enough going on to warrant the duration of a given section of a story.

Potential pitfalls of longer scenes include feeling they’re too repetitive, static, or longwinded. But if you merely separate a scene into distinct sections or “movements,” you immediately can create substantial surprise and variety. The midpoint of the opening scene in Inglourious Basterds when Tarantino reveals Shosanna’s family under the floorboards is the classic Hitchcock example of the bomb under the table to create dramatic irony. This drastically changes how we experience the remainder of the scene.

F.B.: In your section on “the language of visuals” you illustrate character foreshadowing in Air Force One when President James Marshall (Harrison Ford) spots a milk carton. Describe how this becomes an “aha!” moment.”

Film is such a visual medium that we should constantly be looking for ways to bring to life what is inside a character’s mind. This might be done in a masterfully creative and profound way. Think about the subjective whims of the character’s inner life in Fellini’s Amarcord or 8 1/2. Here is a simple, practical usage of this craft. In Air Force One, the [president] is trying to sabotage terrorists who have hijacked the plane. The image of liquid spilling from a container simultaneously inspires the character’s thoughts and reveals them to us. We get a sense of his mind working and visual foreshadowing for his next action of “dumping” fuel from the plane.

F.B.: I found the hundreds of scene examples that you include and analyze to be not just insightful but great reading for anyone interested in the art of storytelling. For example, your chapter on dialogue is wonderfully instructive in illustrating how dialogue can and should be more than everyday conversation.

You can thank screenwriter Budd Schulberg for the memorable dialogue in On the Waterfront, 1954.

J.M.: When I was demonstrating “how not to do” something, I avoided using a real example from a writer or film. This allowed me to have fun in creating original ones like my take here on bad dialogue:

BAR PATRON: I have this feeling that if I were a bit more focused or lucky or, well, I don’t know, maybe if you would have supported me more, I might have a better job and stuck to my diet.

If I were to try to unearth and summarize a beat — the underlying action — buried in this rambling rant, I might suggest “to whine” or “to complain” or possibly “playing the victim.” Even if this sounds natural, it’s not dialogue. Dialogue is not mere conversation. Great dialogue exists when the words align with the beats of the scene and deliver a powerful emotional subtext of implied conflict and meaning.

Compare this to the dialogue in the classic scene from On the Waterfront in which Marlon Brando’s Terry calls his brother Charley (Rod Steiger) on his betrayal. On their way in a cab to see the mob boss Johnny Friendly, Charley implores Terry to agree not to “rat” on Friendly. If he doesn’t agree, Charley will be killed. A moment later, Charley brings up the past.

CHARLEY (nostalgically): Gee, when you weighed 168 pounds you were beautiful. You could’ve been another Billy Conn. That skunk we got you for a manager, he brought you along too fast.

He’s not just reminiscing. He’s so overwhelmed with the guilt and responsibility in the moment that he’s trying to rewrite the past, so his brother might see it his way and let him off the hook and relieve him of responsibility. What follows is the heart of the famous monologue. It culminates in these two lines. Terry appropriately put the responsibility back on Charley, who tries to avoid it:

TERRY: You was my brother, Charley. You shoulda looked out for me a little bit.

CHARLEY (defensively): I had some bets down for ya. You saw some money.

Do you see how strong these beats are? Despite Charley’s attempt to avoid blame for his sins, Terry’s final few lines are a powerful push to get a confession or a taking of accountability for sins.

TERRY: You don’t understand. I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody instead of a bum, which is what I am, let’s face it. It was you, Charley.

Charley accepts the responsibility and lets Terry get out of the car. He’s acceding to his own death which has a subtext of “I will sacrifice my life for you.”

F.B.: In the much longer opening scene of the epic western Once Upon a Time in the West, you dissect the ways that nonverbal beats can interact with terse, minimalist lines of dialogue. It’s the scene where Harmonica (Charles Bronson) has arrived by train for a showdown with antagonist Frank (Henry Fonda).

J.M.: In fact, the terse minimalism is the beauty of those lines. Harmonica sees three henchmen and three horses and responds:

HARMONICA: You bring a horse for me?

The seemingly banal question has the subtext of “I know you are here to kill me” or “Are you here to kill me?” The head henchman admits, “Looks like we’re shy one horse,” which announces, “Yes, we’re here to kill you,” with the intention of rattling him to gain the advantage. Harmonica turns the table with the classic line:

HARMONICA: You brought two too many.

Surprise: He implies that he is going to kill them. On a superficial level, it’s cool and clever, but Harmonica’s life is at stake, so the line serves the beat and dramatic purpose of intimidating them in an attempt to gain any possible advantage.

Again, great dialogue is not mere conversation. It’s a purposeful craft that synergizes with all the elements of the story. In On the Waterfront, Charley’s “confession” rhymes thematically with the fact that Terry has just confessed to Edie about his involvement in her brother’s death. The dialogue in Once Upon a Time in the West cleverly draws from the iconography of westerns as well as the specifics of the setting to reveal Harmonica’s cunning instincts.

F.B.: What are some of the changes you’ve noticed in how scenes have evolved from Hollywood’s “studio years” to present-day filmmaking?

Robert Shaw’s character had a definite way with words in Universal’s Jaws, 1975. (Wikipedia.)

J.M.: Scenes have gotten shorter, but movies have gotten longer. The average feature in 1930 was about 90 minutes whereas today it’s about two hours. My breadth of examples draws from the old and the new and from classics and commercial fare. I might reference Moonlight, Citizen Kane, and Bicycle Thieves in the same chapter I mention Superbad, The Dark Knight, and Napoleon Dynamite. But I’m not a film historian and the book isn’t about making profound conclusions about the past versus the present.

Even when I analyze craft or devise a theory, my ultimate goal is to inspire and create a connection between two seemingly unrelated skills or lesson. For instance, I want young writers to look at monologues such as the dramatic not-safe-for-work moment in Last Tango in Paris in which Brando’s character talks to his dead wife in her casket, or the famous Robert Shaw “Indianapolis” speech in Jaws and learn the skills to write a comedic monologue.

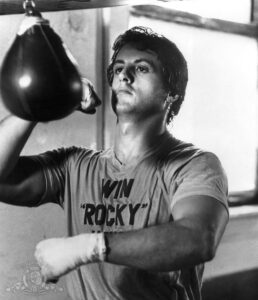

F.B.: You maintain that theme is the truth about the world conveyed in your story, and you cite Casablanca and Rocky as examples. Explain.

Sylvester Stallone earned an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay for his debut starring role in Rocky, 1976. Repeat after me: “Yo, Adrian.”

J.M.: Rocky doesn’t require intense analytical scrutiny. You can practically “feel” the theme(s): Go the distance. Love is winning. You don’t have to win to be a winner.

In Casablanca, the craft is a bit more prevalent.

Rick starts off hating himself and Ilsa. And he is politically indifferent. But this means there are several opportunities for love. He can learn to love himself. He can rekindle the romantic love between him and Ilsa. And he might develop a desire or passion in relation to the current political environment.

It’s not too hard to envision an ending to Casablanca where Rick wins back the girl and runs off with her. He would achieve “romantic love.” However, the reason the movie is considered one of the greatest love stories ever told is the fact that he chooses “all love.” Rick stops hating himself. He honors the love between him and Ilsa without having to possess her as a lover. And this love plays out as a political choice, too, when he gives her and Lazlo the letters of transit and shoots the German Major Strasser. There even is platonic love with Renault in the film’s final line: “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Love abounds. It’s more than romance, politics, or friendship. There is a higher and bigger love.

Thanks to Jim

That final assessment of thematics in Casablanca, for me, goes to the heart of how The Craft of Scene Writing engages the reader and how the book’s content promises so much for anyone wanting to learn more about the art of storytelling.

I agree wholeheartedly with the back-of-the-book blurb contributed by Heidi McDonald (Digital Love: Romance and Sexuality in Games). “This book may well change how screenwriting is taught,” she says. “[It’s] an eye-opening approach to storytelling that will benefit screenwriters and novelists alike.”

I wish it had been available to me and my Michigan writing students way back when.

Margaret R BENNETT - 58, 75

I’m going to recommend this story to my 18-yr-old grandson who plans to attend EMU next fall. He will major in film-making.

Thanks!

Reply

Barbara Seiden - 1968

I was a fellow classmate of Frank’s in Radio-TV classes taught by Dr. Edgar Willis and Professor Edward Stasheff at the University of Michigan, and also studied playwriting under Professor Kenneth Rowe in 1967-68. I still have his iconic “Write That Play” in my library along with the training books of Dr. Willis and Professor Stasheff. From their valuable tutoring and mentoring, I went on to have a career in Hollywood as a playwright and assistant writer for “Bewitched” and ABC-TV where I recommended “Love Boat” to be made as a “Movie of the Week.” That movie was later a spin-off for its own series. The University of Michigan Speech Department in the Frieze Building turned out many successful students from my department, including Frank, Lawrence Kazdan and Gilda Radner. I was fortunate to win the coveted Avery Hopwood Award for a dramatic radio play and short story during my college years and able to forge a career in this business owing to the valuable guidance and professional wisdom of these great teachers. I currently edit my son’s books and write for film, television and the stage. I think film writing has definitely changed over the years. Aaron Sorkin, who I greatly admire, and others have developed a faster paced, more clipped style of writing and production, causing the viewers to concentrate more and use more of their brain to keep up with the plot and action. I agree that writers need to concentrate on the beats of the product, whether it is a book, film or TV script they are writing. It is the beating heart of the story in more ways than one!

Reply