Trash walkers

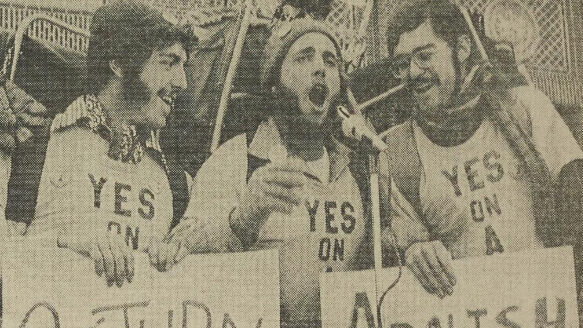

In mid-October 1976, a crew of college-aged men and a middle-aged professional trudged East along Michigan’s U.S. 12. They wore matching yellow T-shirts that read “Yes on A!”

Tim Kunin, Jeff Ross, and Tom Moran (pictured above, in The Michigan Daily) were members of the Public Interest Research Group of Michigan (PIRGiM). They had set off from the shores of Lake Michigan near Benton Harbor and planned to trek 230 miles on foot through Paw Paw, Kalamazoo, Battle Creek, and more. Along the way, they were joined by Russ McKee, the editor of the Department of Natural Resources’ magazine.

Prior to passage of the bottle bill, consumers threw bottles and cans in the trash — or in the alleys of Ann Arbor. (Image: Ann Arbor News, 1965.)

Their final destination was Detroit’s Belle Isle. The goal: to pass legislation to reduce litter and trash statewide.

Approaching Jackson, the men were a little worse for wear. Logging about 20 miles a day, they’d endured rain, sleet, and hail as they generated interest in the cause. As they did on most stops, they alerted the media in town that a compelling “photo op” was in the making: They were going to collect roadside trash for one mile.

“We got so much litter, we stopped at half a mile,” says social activist Dave DeVarti, a lifelong Ann Arbor resident. He was part of the campaign’s logistics team.

Momentum picked up as the election approached. Members of PIRGiM, the Michigan United Conservation Clubs, and the League of Women Voters, working with other nonprofits, triumphed when the state’s voters approved Proposal A, the Beverage Container Act of Michigan. The margin was 2-1, despite well-funded, bitter opposition from the bottling industry and grocers.

The bottle bill

Today, many Michigan residents take recycling in stride, while some may well count on those bottle deposits to supplement their finances. But Michigan’s “bottle bill” might never have happened if not for the creativity, passion, and perseverance of local and student activists managing operations from the 4th floor of the Michigan Union.

DeVarti, Greg Hesterberg, and Tim Kunin are three of those activists. All three bearded with glasses, they met working on the bottle bill as part of PIRGiM, and recall a heady time in Ann Arbor, as voters took on civil rights, tenant rights, environmental rights, and women’s rights to name a few.

“People didn’t like a river in Cleveland being on fire, or the documented death of Lake Erie,” DeVarti says. He had a front-row seat to all manner of campus unrest from Casa Dominick’s, his father’s restaurant near the Law Quad. His voice rises with passion as he recounts those days.

DeVarti first got involved in ENACT — the U-M-based Environmental Action group — as a student at Ann Arbor’s Pioneer High School. The bottle bill turned out to be a natural outgrowth of his early experience; it was ENACT that planned and carried out the first Earth Day on March 15, 1970.

“Everyone else in the country set April 22, but U-M was on the semester system and that would have put it during finals,” he says. “So they planned it for shortly after Spring Break. I still think of organizing ‘Earth Day week’ at Pioneer as my most formative, important experience of high school.

“While I was involved with ENACT, PIRGiM started forming,” he continues. “Ralph Nader came up with a model for student organizations to pay a $1 fee to state PIRGs, and the professional staff would represent the students’ concerns. There was a local board on campus and a state board of directors. [Hesterberg and Kunin] were on the state board.”

DeVarti, who took a few ‘gap years’ after high school, was in his junior year at U-M when he convinced law student Hesterberg to join him in a petition campaign to get the bottle legislation rolling.

“Bills were introduced in the House — and shot down — numerous times over previous years, from opposition by Joe Mack,” says DeVarti, talking about a Republican from the Upper Peninsula who was, at that time, the most powerful person in state government.

“Joe Mack was famous for saying, ‘These environmentalists come to the UP with a $5 bill and a pair of underwear, and they don’t change either one.’” DeVarti cracks up at the memory.

But if the bottle bill was going to make it out of committee, it would need to get onto the ballot via citizen’s initiative, which was a serious undertaking. So that’s what they decided to do.

Don’t stop me now

The Jackson Citizen Patriot carried the news, as the walkers gathered huge mounds of trash during the campaign.

Kunin was in his third year at U-M, studying political science and economics; Hesterberg had begun studying at the Law School after receiving his undergraduate degree from the University of Maryland.

Tom Moran, ’77, was a student in the School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS), aka the School of Natural Resources at the time, when he joined the cause. Since the group was strapped for cash and other resources, Moran proposed the walking stunt as a way to take the cause “viral.”

“I got the idea from ‘Walkin’ Lawton’ Chiles in Florida,” Moran says. “He ran for Senate and won. He walked 1,003 miles from Pensacola to Key West. He later went on to be governor.”

Moran convinced Ross and Kunin to walk the width of the state with him. McKee, the DNR magazine editor, joined them about two days in. He was the one who made the matching T-shirts that read “Yes on A.”

As talked to voters, the activists distributed mimeographed sheets calling for a “Return to Returnables.” They spoke with reporters and posed for pictures. They collected bags and bags of trash. And they learned life lessons about elections, campaigning, and public relations.

“I learned a lot about the media,” Moran says.

Newspapers statewide often pictured the young men roadside with oversized signs roped to their backpacks: “Save Money. Buy the Beverage. Not the Bottle. Yes on A.” A scrapbook Ross kept includes about a dozen local newspaper articles and photographs of them. Students from MSU drove a caravan down to cheer them on, according to one report, and Girl Scouts collected nonreturnable cans along the highway, in solidarity. (In two hours they had 125 cans.) Hesterberg shuttled walkers to overnight lodgings in his ’76 Mercury. And even though they missed two weeks of school, Moran says he earned six independent studies credits from Professor Jim Crowfoot.

Ann Arbor welcomed them back for a Homecoming rally on the Diag before the crew made the final walk toward Detroit. They arrived on Belle Isle on Saturday, Oct. 30, three days before the election. Supporters pitched in to clean up the island. There could be no better closing argument to pass the bill than the huge mound of garbage they’d collected together.

From concept to reality

During an interview for a U-M Bicentennial StoryCorps, in October 2017, DeVarti noted: “We didn’t have the money to put forward on the campaign, but we wanted to make the case and do it in a way that would appeal to people. Because we were able to do this as a petition drive, and not through the legislature, we went for a 10-cent deposit. It was the highest deposit in the country.”

Prior to the walk, the activists mobilized U-M students to vote “Yes on A” in another brilliant scheme that would change their own fortunes. When U-M played Wake Forest, the PIRGiM activists distributed 40,000 flyers outside the stadium on game day. The flyers listed each team’s roster, along with basic information about the bottle bill.

“You normally can’t get people to take political flyers when you’re handing them out at games,” DeVarti says, “but they snapped these up. Just a simple thing like having [the rosters printed on them] made all the difference.”

Turn the page

A few years later Kunin, Hesterberg, and DeVarti expanded that publishing concept to form Ann Arbor’s Sport Guide Inc. (later SGI Publications). Initially, they printed basic football programs and distributed them for free outside Michigan Stadium.

“These ‘programs’ were popular with the student fans, who weren’t about to pay a whole dollar for the University’s official programs,” says Kunin. His partners credit him with creating SGI’s newsprint tabloids, known as the Michigan Football Guides.

“At first, the Athletic Department blamed us for cutting into their sales,” DeVarti continues. “But soon they realized if someone would pay $1, they’d pay $2, and they ended up making more money, thanks to us. Not that they ever did thank us.”

In fact, he recalls a time when one of then-Athletic Director Don Canham’s “henchmen” tossed a couple dozen bundles into a dumpster. “Our distributor, Mark Frisch, saw him do it, chased him down, and retrieved the bundles.”

Later, the fledgling publishing firm expanded its offerings to include the Michigan MoneySaver coupon books and the Cinema Guide (which aggregated film schedules across campus). In 1989, when home videos killed off campus cinema, that publication morphed into a monthly entertainment format, called Current magazine; Toledo-based Adam Street Publishing purchased Current in 2007.

After that sale, SGI Publications disbanded and Kunin and Hesterberg went on to launch EcologyFund.org with the goal of saving the rainforest. It branched out into a pantheon of “click-to-give” websites and web-based marketplaces, driven by social media and e-news, called GreaterGood.com. It includes the Breast Cancer Site, the Hunger Site, the Animal Rescue Site, and six other causes which harness the collective, communal energy of social activists who want to do good in the world.

Their nonprofit foundation, GreaterGood.org, has donated $57 million over the past 19 years, fosters fair-trade enterprises, and built a school in Haiti. That total includes close to $500,000 since 2009 to Michigan Medicine for breast cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s research. Kunin and his wife, Susan Guzman, also funded an LSA scholarship in honor of her father.

Flying not walking

Hesterberg lives in Santa Barbara, Calif., but commutes to Seattle several days a month for business; Kunin splits his time between offices and homes in Seattle and Minneapolis. Moran, who came up with the cross-state walk idea, retired from a decades-long career as a mail carrier and now drives a bus. Ross completed his undergraduate studies at UC Berkeley, and then earned his law degree from there, and worked as a civil rights attorney at his own law firm for 22 years. Now he is full-time mediator.

McKee passed away in 2010, at age 85, in East Lansing. In a long, accomplishment-filled obituary — which includes service during WWII, lobbying to get DDT banned, and publishing numerous best-selling books — there is a single sentence that simply states, “He also helped get the returnable bottle bill passed in Michigan.”

DeVarti, Kunin, and Hesterberg left U-M prior to completing degrees. DeVarti remains active in Ann Arbor with business cards that read: “Creative Person” and “All-Around Good Guy.” He serves as a trustee on the board at Washtenaw Community College. In addition, he serves on the Ann Arbor Zoning Board of Appeals and the Ann Arbor Film Festival board. He served as a member of the Ann Arbor City Council and Planning Commission in the ‘80s and served on the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority from 1991-2007.

“I think of myself as a community activist,” he says.“I work in my own community, I can be the point person if I need to be, but I’d rather encourage others to be leaders.”

Meanwhile, DeVarti, Hesterberg, and Kunin’s core group of fellow PIRGiM activists also remain committed to social justice causes all these years later: “Dale Ewart works for SEIU in Florida,” DeVarti says. “Bea Hanson works in violence prevention against gays and women; Tim Carpenter does tenant organizing and homeless issues in Chicago; Gary Claxton is at Kaiser now, doing health care advocacy research.”

“Look at what they are doing, still involved in fighting for social justice, in government, unions, community organizing, or in life outside of jobs and families.”

Law and order

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uGu4AwL5Kho

So few laws seem to actually change the world — tangibly — so it’s gratifying to celebrate one that did: Michigan’s Beverage Container Law went into effect in December 1978.

Soon after, Michigan saw a 96 percent return rate on aluminum soft-drink/beer cans, and plastic and glass bottles. Some four decades later, the state’s return rate is still the highest in the nation; sadly, however, overall recycling is near the bottom, barely 15 percent. (2016 State of Michigan Report on Recycling.)

Looking back, DeVarti is proud of the achievement, but still sees challenges ahead.

“It’s the best bottle bill in the country,” he says. “It’s motivated people to make $60-$100 collecting cans and bottles for returns at Michigan Stadium who could probably use the money. And it’s had a significant impact on decreasing litter. But it’s had some shortcomings. Whoever imagined ‘bottled water’ or carbonated water would be a thing. Those bottles are strewn all over.”

A 1971 PSA to “Keep Ameria Beautiful” features a man dressed in Native American garb with a tear rolling down his cheek at the sight of a litter-strewn land. DeVarti still resonates with the voiceover.

“People start pollution,” intones the narrator. “People can stop it.”

Richard Levick - 1987 (MS)

I had the honor to work with Dave, Tim, Greg, Gary, Tom, Bea, and so many of the people quoted in this article, when I worked at PIRGIM-UM as a young staffer in the late ’70s and, eventually as the statewide Acting Director in the early 80s. I was well aware of this story – this legend – as an undergraduate at Maryland’s PIRG and it is a big part of what inspired me to move to Michigan and join these visionary activists. The tear in my eye from reading this article is how well you captured a moment in time and its inspiration for a generation. As the CEO of an international communications firm today, I constantly use the lessons learned from those days. Thank you, Dave. I miss you, the gang and Dominick’s!

Reply

Lisa Powers - 1986

Thank you, Richard! These legends are very real, and work amongst us every day to make the world better. I’ve been inspired by their example for decades, and it’s great to hear from you and others who feel the same.

Reply

Barbara Bach

I have some yellow bottle caps in my kitchen drawer… advertizing the bottle bill, having worked as Leg.

Asst. to Rep. Perry Bullard at that time!

BBB

Reply

Lisa Powers - 1986

How fun, Barbara! The many creative ways they got the word on the bottle bill contributed to its successful enactment. You were a part of that amazing era, congratulations!

Reply

Martine Mickiewicz - 1985 1991

I’m so proud to know Dave, Tim, and Greg…and to have worked at SGI. Kudos, Lisa, for bringing to light all the hard work they did helping to pass the bottle law!! Well done!

Reply

Lisa Powers - 1986

Much appreciated, Martine! We were a part of SGI during an amazing era, and if you’re like me, we still carry the glow of friendships formed there in our hearts.

Reply

Michele Mickiewicz - 1981

This is such a great accomplishment. The law in California isn’t half as effective as the one these guys created in Michigan. What a big difference this has made for the environment! Thank you!

Reply

Lisa Powers - 1986

Thanks, Michele! All of Michigan is benefitting from their hard work, vision, and dedication to this — and many other — pieces of legislation that they helped to promote.

Reply

Harvey Pillersdorf - 1969

Thank you Lisa for your journalism. I appreciate some stories I’ve heard over the past 35 years, having been documented here. I worked with Greg, Dave, and Tim for almost 20 years, garnering funds to support what became almost a dozen differently titled publications. Overhead, of course, included supplies, equipment, and printing costs, and also salaries of some of the smartest, most creative, and dedicated people I’ve known. I believe that the men who led by attending to something bigger than themselves, modeled for a cadre of others who continue to do important things for reasons bigger than ourselves.

Reply

Lisa Powers - 1986

Thanks so much, Harvey! These stories were too important to not have collected, for posterity, in one place. Your work, and everyone’s at SGI, helped bolster these bigger efforts that were going on behind the scenes, juggled during and between deadlines for the magazines. Dave, Greg, and Tim certainly modeled how to create community and strengthen our sense of responsibility toward each other in a larger way. And you’re so right, it allowed so many of us to accomplish our personal dreams and goals in service to bigger ideals.

Reply