Christmas craziness

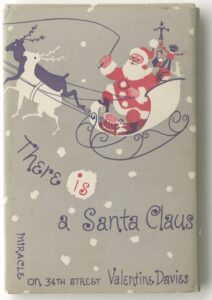

Valentine Davies wrote the story that would inspire the screenplay for ‘Miracle on 34th Street.’ Then he wrote a short novel to cross-promote the picture. (Harcourt Brace and Company, Inc., 1947.)

During World War II, a young writer named Valentine Davies, BA ’27, served stateside in the U.S. Coast Guard. Midway through the war — Christmastime 1943 — he got an idea for a story.

What would happen if Santa Claus — the real Santa Claus — found himself stranded in an iconic department store amid the commercialized chaos of an American Christmas? What if he got a close look at the rapacious retailers, the sloganeers and price-gougers, as they hid their greed under hypocritical claptrap about “goodwill toward all men”?

Davies scribbled a summary of characters and how the story might take shape — a charming old gentleman who claims his name is “Kris Kringle”; a chance encounter with a department-store manager who needs a substitute Santa in a pinch; a cynical little girl who’s been taught that Claus is merely a myth … and so on.

Davies brought his notes to a good friend he’d made back in Ann Arbor, George Seaton, an actor-turned-screenwriter/director. Davies said: See what you can do with this. Seaton got to work on a script.

Before long, the two writers were collaborating on a Hollywood film set. (That’s Davies, above and right, with Seaton.)

“Just a … little extra picture”

After winning the Oscar for Writing (Motion Picture Story), Valentine Davies (right) takes a moment backstage with presenter George Murphy (center) and future bestselling novelist Sidney Sheldon. (Image: The Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences.)

Seaton’s screenplay was first titled The Big Heart (Davies’ idea), then My Heart Tells Me, then It’s Only Human, then — finally — Miracle on 34th Street.

Twentieth Century Fox executives bought it but cast only one bona fide star — Maureen O’Hara as Doris Walker, an embittered divorcee determined to disenchant her daughter — and released it as a minor feature in the spring of 1947, of all times of the year.

“They had no high hopes for Miracle whatsoever,” recalled the actress Natalie Wood, who was cast as the Santa-skeptical Susan at the age of 8. “It was just a sort of little extra picture that was done on the sideline.”

The executives underestimated it.

Miracle won three Oscars — best original story for Davies; best screenplay for Seaton; and best supporting actor for Edmund Gwenn as Kris Kringle.

Then, gradually, it gathered steam to become one of the longest-lived and most-loved specimens of Christmas cinema. The film has been deployed via every possible delivery system: the big screen, TV reruns, video cassettes, DVDs, streaming services. It was remade for television, radio, and the musical stage, then as a new theatrical release in 1994. In 2005 it was selected for the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry, which ensures the preservation of movies deemed to be “of enduring importance to American culture.”

Somehow, Valentine Davies’ pencil had pinned a scrap of magic to the page.

Ann Arbor to Hollywood

Davies was hardly the first writer to be dismayed by the yawning gap between Christian ideals and modern urban civilization. To take just one example, W.T. Stead, a British journalist of the 1890s, had attracted a huge readership with an exposé of the underworld economy titled “If Christ Came to Chicago.”

But Davies had been schooled in popular entertainment, not social science. When he got an idea, he considered its potential as drama. He’d been thinking along those lines at least since his college days.

Born in New York City in 1905, he grew up as the son of a well-to-do real-estate man. But business was not for him. When he arrived in Ann Arbor to start college in 1923, he plunged into U-M’s thriving theater scene.

Starting as a freshman, Davies took up criticism for the Michigan Daily, reviewing plays, movies, and music performances from professional productions in Detroit to the amateur Ypsilanti Players to the Michigan Men’s Glee Club.

At the same time, he performed in student plays and musicals, working his way up the ranks to write the show for the 1926 Michigan Union opera, an elaborate production that toured major cities.

Davies met his future wife, Elizabeth Strauss, acting in University productions. (Image: Michigan Daily.)

While still a sophomore, Davies had been chosen by U-M’s Comedy Club to direct and design the sets for three one-act plays. He also acted in two of them, one of which was “The Man in the Bowler Hat,” by A.A. Milne, better known as the author of Winnie-the-Pooh.

In that production, Davies took the stage alongside Elizabeth Strauss. She was a year older and the daughter of Professor Louis Strauss, chairman of Michigan’s English Department. The two acted together in several more plays, and soon after Strauss’ graduation in 1926, they were married.

Davies earned a graduate degree at the Yale Drama School, then went to work as a playwright. Three of his efforts made it to the stage, including Blow Ye Winds (1937), which attracted interest in Hollywood. So Davies, Elizabeth, and their two children went west in pursuit of bigger paydays in the movie business.

He earned screen credits for one “story” (a short outline or synopsis of a movie) and one screenplay. Then World War II was on; the Coast Guard beckoned; and Davies found himself in a crowded department store, pondering the true meaning of Christmas.

The core of a classic

It’s unclear which marketing wizard decided to release ‘Miracle on 34th Street’ in May. (Image: Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences.)

A million Christmas movies have been made over the years. What turned Davies’ idea into a classic?

One ingredient may be its realism. It’s a modern-day fairy tale, of course. But the fantasy shows Christmas in the heart of Manhattan, the belly of the urban beast, with settings from the vast sorting room of a U.S. Post Office to the psych ward at Bellevue Hospital to the chambers of a city judge consulting his machine-politician boss. There are no elves or flying reindeer in Miracle. It’s set in the real world, and that makes the fairy tale more believable.

Another is surely its theme.

Run-of-the-mill Christmas tales are built on the idea of generosity — the giving of gifts. But the classics have quite a different motif — transformation.

In A Christmas Carol, Marley’s ghost and his fellow spirits reveal to Ebenezer Scrooge the follies of his life — and he is changed.

The Grinch hears the Whos singing their joyous hymn on the Christmas he has just stolen — and he is changed.

In It’s a Wonderful Life (released the same year as Miracle on 34th Street and still going strong), the angel Clarence helps George Bailey understand how much his small-town life has mattered — and George steps back from suicide.

This special gift-wrapped edition of the novel was released for Christmas to promote the film, which was still playing in U.S. theaters. (Image: Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.)

So it is in Miracle. A real-life Santa brings the wonder back to Christmas and a disillusioned mother and daughter are rescued from cynicism. “Believe and you shall be saved.”

The gift that keeps giving

Davies’ success with Miracle sparked an upward trajectory in his career. While his own story was being adapted, recast, and remade in multiple formats, he continued to churn out more film treatments and screenplays. He wrote The Glenn Miller Story (1954), starring Jimmy Stewart; then wrote and directed The Benny Goodman story in 1956. He adapted the novel The Bridges at Toko-Ri into a screenplay that paired William Holden and Grace Kelly on film.

Davies also gave back to show business. He served as president of the Screen Actors Guild, then of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

He died at age 55 in 1961. According to the friend who was with him, Davies’ fatal heart attack was brought on by a deep-bellied laugh.

Top image: Writer-director George Seaton, left, and writer Valentine Davies during film production of “Miracle on 34th Street.” (Image: Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.)

Sources included The Michigan Daily; “Valentine Davies is Dead at 55; Led Motion Picture Academy,” New York Times, 7/25/1961; Suzanne Finstad, Natasha: The Biography of Natalie Wood (2001); American Film Institute Catalog and Film Reference. For the theme of Miracle on 34th Street and other classic Christmas stories, see Ted Byfield, “If You Think Christmas is about Giving, Then Take a Closer Look,” Alberta [Canada] Report, 12/24/1996.

Holly Anderson - 1972

This is a delightful article about an amazing author from University of Michigan. I learned facts about this author that bring new insights into his work, “Miracle on 34th. Street” . I’m proud to be a Michigan alum!

Reply

William Thomas - Law 73

The film was condemned by the Legion of Decency……it portrayed a divorced woman in a positive life…..having a real job and raising a child on her own…..think of the social chaos !!

Reply

Anne Remley - 1952

A favorite memory of my husband, Fred Remley (class of 1951), was the night in early 1948, listening to the Oscar’s ceremony on the radio, along with his West Quad roommate, John Davies, Valentine’s son. John and Fred were thrilled at the unforgettable moment when Miracle on 34th Street won the award.

John and Fred remained friends for many decades thereafter and once drove in a jalopy across the country to visit John’s Hollywood family. John and his wife returned many years later for a class reunion, likely the 50th, and the old roommates greatly enjoyed visiting their West Quad world again.

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Thank you for making my day. This is the kind of comment we live for. What a charming addition to the story. Thank you so much for sharing. (Ed.)

Reply

Mary Cheng - ‘84 LSA, ‘88 MD

Thank you for this wonderful article about Valentine Davies. I always enjoy learning about the Michigan connection to sports, history, and the arts.

The sentence that caught my eye for two reasons was “…dismayed by the yawning gap between Christian ideals and modern urban civilization.” Firstly, because the author acknowledged the Christian origin of ideals at that time, and referred to an article titled ”If Christ came to Chicago” in the following sentence. I find this refreshing in a time where some feel skittish about ANY mention of religion.

Secondly, because that sentence sadly still applies today. Kris Kringle would be more appalled by the “gimme gimme get get get” of this millennium, especially when he discovers he’s been replaced by amazon prime immediately after Halloween. And… what would he think of Black Friday?

Keep up the good work Michigan Today!

Reply

Jeffrey Lazar - '69 LSA '74 MED

I have loved this story since childhood. Mom has an original copy of the book; sadly, I don’t know what happened to it. I watch the original movie (B&W, of course) every year at Thanksgiving.

Your piece about Mr. Davies was beyond fabulous! Thank you.

Go Blue

Reply

James Tobin - 1974, 1986

Thanks for your note. That’s how I first encountered “Miracle,” too — as a treasured TV rerun just once a year, on Thanksgiving Day, long before we could order up practically any movie ever made at the push of a button.

Reply

Val Edwards - 1970 AMLS

Great story. I loved the combination of history and literature and hope for more articles like this. I do enjoy reading Michigan Today. Thank you, too, for Mary Cheng’s comments that rang true with me As well and all I can say is “ditto.”

Reply

John Jay - '67 LSA

What an interesting article! This wonderful film is part of our annual Christmas Eve family movie marathon, during which my husband and I watch 3 films without fail: “Miracle”, “White Christmas”, and “Polar Express”. How nice to know there is a University of Michigan connection to two of those movies: the above cited revelatory example for “Miracle”, and former U-M student Chris Van Allsburg’s authorship of “Polar Express”. In yet another State of Michigan connection to “Polar Express”, the former Pere Marquette railroad’s restored steam engine #1225 (housed in Owosso) is the prototype for the locomotive in the movie. We owe an early ’70s student railroad club at MSU much credit for the initial preservation that beautiful machine.

GO BLUE!

Reply

Deborah Holdship

John Jay: In case you missed it, here’s a fun 2018 Q&A with Chris Van Allsburg. Enjoy! https://michigantoday.umich.edu/2018/01/18/take-a-giant-step-outside-your-mind/

Reply

John Jay - ‘67 LSA

Thank you, Deborah. I had indeed missed it.

Reply

Amarendra Kumar - 2019 EMBA

Beautiful story! Thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

Reply

satya deva - 2001

Nice article thank you so much sir for sharing your knowledge and ideas

Prosthesis

Reply

Don Parshall - Dearborn '76, Law, '79

This movie was a Thanksgiving Day staple for me growing up in Detroit in the 1960’s (Bill Kennedy at the movies always showed Miracle on 34th St at 1:00pm). Many wonderful actors in this movie: William Frawley, John Payne, Gene Lockhart and Phillip Tongue. An added bonus to the main plot for a fledgling lawyer was the “lunacy” trial near the end of the movie…Great to hear about the UofM connection!

Reply