As a high school senior, Fitzgerald was just beginning to experience that schism in academia. Assigned to the labor beat as a young Michigan Daily reporter, she SOON WAS IMMERSED in the campus struggle to end sex discrimination.

As a student journalist she engaged many of the players who helped pass what we now know as Title IX. There was local Democratic organizer Jean Ledwith King, one of only 10 women to graduate in her Michigan Law Class. There was the grad student journalist named Kathleen Shortridge who used her investigative reporting skills to gather the damning statistics demonstrating bias. And to a lesser extent, there was President Robben Fleming’s protege Barbara Newell, the first woman to break the VP ranks at Michigan.

King led the Ann Arbor chapter of FOCUS on Equal Employment for Women that in May 1970 filed its first complaint with the Dept of Health Education and Welfare. HEW launched an investigation into sex bias on the U-M campus, and thus began the long legal slog to the Education Amendment Act of 1972. The act encompasses Title IX, which bars sex discrimination at colleges receiving federal support; it also amended the Equal Pay Act to include women in professional and administrative jobs in academia.

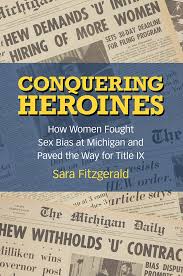

Fitzgerald’s book, “Conquering Heroines: How Michigan Women fought sex bias at Michigan and paved the way for Title IX,” argues that while hundreds of similar complaints were filed against U.S. colleges in 1970-71, it was the complaint brought by the Michigan women that broke through and set the template for future complaints and settlements. She sees the story as something of a thriller – albeit a stealth bureaucratic one without great photos – in which Michigan’s women (many of them support staff) subverted the system to bring it down from within.

Fitzgerald, a former editor at the Washington Post, remembers the first time she felt the visceral gut punch of sex discrimination; it started when she was accepted to both Stanford and U-M. Here’s Fitzgerald…

FITZ: I’ve thought a lot about click moments, because a lot of these women had qlik moments of the term that Ms magazine, which was founded during the years I was Michigan, one of their early articles kind of came up with that concept. And back then, most of my peers did not apply to all the colleges that young people tend to do now. I mean, people will have like seven different applications. I applied to two schools, chigan and Stanford. And in this, that was in April of my senior year, I got accepted into Stanford and I took down my letter of admissions in to talk to my father about it and he said, Well, I have him and my parents I should I should say, we had a they had two girls and two boys and I We said they had tried to treat us all equally in terms of our opportunities and financial support for our interests and so forth. But when I took this down to my father and showed me, he said he wasn’t prepared to pay the cost of tuition at Stanford when I could get an excellent education And it would have been fine if he had stopped there. But he went on to say, because I figure if you’re not married, by the time you graduate from college, you will be soon afterwards. And it was the first time that I ever experienced that. My father viewed my aspirations differently than he probably viewed my brothers

DH: OK, that’s what the editors of MS. Magazine called a “CLICK” moment, where suddenly you view your situation from a new perspective. As Fitzgerald would learn, the impact of that moment stays with a person.

FITZ: When you go back to these times, at this stage of our lives, we often forget a lot of the details. And it brings those memories to the fore for some of the faculty members who are older than I am that I’ve been in touch with, I found that the memories are still involved a lot of pain and anger. And you know that, you know, they’re happy that has been captured. But I recognize that it was very difficult times for them. And at the same time, I want to write it for younger generations, both men and women, but for them to realize of what women before them did that the battles aren’t over yet. you know, this is also the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage. And we go back and we revisit these eras and we look at them with new eyes and learn that our victories are built on the shoulders of of women or leaders who went before us and I think those are important lessons.

I did realize in working on this story, that it did have some suspense, and it was in a little way of thriller and had some clandestine, you know, aspects to it. There were a lot of things at stake and, and also, some of the people involved were colorful characters that I think had interesting backstories and so I hoped I could make it interesting and, you know, to keep people turning the pages and so, you know, the readers will judge that but, you know, I did think it could be made into To a compelling story, because I certainly felt that way about it when I was living through it.

DH: As a Michigan Daily reporter and editor Fitzgerald would experience the story in real time. Each source had a part to play.

Jean King was a woman I knew when I was on the Michigan campus.

She is still alive, but in an assisted living facility in an arbor. And she was someone who grew up in the Pittsburgh area, went to University of Michigan as an undergraduate student in the 1940s. met her husband there, got a master’s degree. She had undergraduate and master’s degrees in history, which I found interesting is that was actually my major and I think she had a good appreciation of history. She then worked for many years in clerical type jobs around the university, which gave her a good understanding of how the university worked. And she worked for a time as a secretary in the psychology department and work with Professor Theodore Newcomb, who is the department Chairman who had a lot of good contacts around the university, which she began to observe it mid career when she had three children at home, she decided and kind of her own click moment, that if she really wanted to be effective and have power within the Democratic Party, she needed to get a law degree. So she went to University of Michigan law school was only one of about 10 women who graduated in her class in the late 60s.

King was trying to set up a practice and and you earn a living as a lawyer. And she got to meet a woman named Bernice Sandler at a professional women;s caucus in New York and Sandler had been a doctor at University of Maryland and got very frustrated when at a time when her department was expanding, was not willing to hire her. And she had someone one of them who was a friendly colleague told her she came on too strong as a woman, which disturbed her. And shortly after that, she had two more episodes in which she had been really put down and she had a supportive husband at the time, and he told her where you’re the victim of sex discrimination, and it was a term she had never heard before. From her part, she thought she had been a victim of injustice, and she set out to find a remedy.

And she was disturbed to discover that the 1960s civil rights laws had excluded academic women from their protections for one reason or another. But she stumbled across this modified presidential executive order that had not gotten a lot of media coverage, at least this aspect of it, and realize that the federal government was now going to monitor sex discrimination by federal contractors. And she connected the dots that Virtually every major university or college was a federal contractor. And this gave her the tool that she needed to begin pursuing the complaints. In the case of Michigan after Jean King met Sandler at a professional Women’s Caucus meeting in New York, King went back to Ann Arbor and began thinking about how this might be pursued. One of the advantages that King and the women she worked with had is they were University outsiders, they understood the university, but they weren’t faculty members or employees at that time. And so they had greater freedom to challenge the university, then faculty members or employees did at the time

You mentioned Kathleen shortridge. And shortridge, was a graduate student in journalism. She had taken a seminar in investigative journalism, and she decided for her seminar she was going to explore sex discrimination at the university and went around gathering statistics and interviewing administrators, and a lot of them, including some of the admissions officials said things that they probably later regretted they did.

She was the source, where I learned in the second semester of my freshman year, that admissions officers had applied a quota of 55% men 45% women, to my freshman class, I had attended a high school in suburban Detroit and 36 of my classmates, it ended up going to Michigan, but I’d never dreamed that I actually had to meet a higher standard than my male peers to get into Michigan. And so shortridge did a version of her story in the department of journalism’s in house publication, and then did some more work on it. And it ran in the daily Sunday magazine, got a big splash.

King connected with her and shortridge provided a lot of communication skills, to first the complaint. And then, over the coming months as an organization called probe, which was a grassroots organization of University Women in a wide variety of jobs began to get organized and Shortridge was one of the leaders and did a lot of work in terms of communicating about their concerns to the wider community.

DH: One insider who played a minor, but important, supporting role was Barbara Newell, an acting VP, in the administration.

When I arrived on campus, Newell was acting Vice President of Student Services and as such, she was the only woman in the top levels of the administration at the time, although she only held her job on an acting basis until they could complete the search for the permanent appointment. She had been a protege of Robin Fleming’s and had worked with him at University of Wisconsin and had gotten to know some of the other presidents of big 10 universities

But I think that she played a different role and Fleming appointed or as the first chairman of the Commission on women, and she launched that organization to do a lot of good work. It evolved after she left, she left Michigan in mid 1971, and within a year or two, became president of Wellesley College and at Wellesley she she founded their Center for the Study of women, which is one of the leaders in its field. And new went on to become Chancellor of the Florida State University system. So they play very different roles. And I think all of the roles are necessary for something like this, they don’t always, you know, get along and share each other’s points of view, but you need a little bit of each, I think, for successful social change.

DH: Once And then, of course, you have the score of uncredited extras who kept the momentum going once the complaint was filed. King relied on this well-placed network to monitor the administration’s response to the government’s investigation. Instead of demonstrating on the Diag, they were digging through file cabinets.

FITZ: It was acknowledged that there were some secretaries who were doing things that might have cost them their jobs, you know, making copies of letters, and secretly passing it on to someone who was leading the activism so that they would be able to take advantage of and in some cases, the activists realized they had to be careful not to telegraph. The actual document or the source of it, because they wanted to protect these insiders who were sharing some of the things that concern them, for instance, that the university presidents were communicating and talking about how they could lobby at GW to call off their regional officials who they felt you know, were overstepping their bounds. It was the kind of thing that until these, they got copies of the letters, they were pretty sure what’s going on. And one of the things that gave me a lot of satisfaction. When I was able to get in the archives all the years later, were to read the actual letters and, you know, see how these presidents were talking about it. And also, in some ways, the kind of disparaging ways in which they referred to this problem and clearly didn’t see it as a problem.

And one of the things that greatly annoyed Jean King when I interviewed her about a decade ago, was that when Robin Fleming wrote his autobiography, he wrote about anti war protests. And he wrote about the black action movements strike, and his strategies for mediating campus protests. But he did not talk at all about this episode, which clearly, to a lot of women on campus was a turning point for them and their different theories about why he didn’t write about it. But you know, King and Fleming did not get along very well. And, and so she viewed it as he didn’t write about it, because he lost. But I think the answer may be a little more complicated than that.

and I think that was one reason why he was a very well respected, nationally recognized university president at the time was because of his skill at keeping, you know, the campus under control in a in a positive way. Barbara Newell, when I interviewed her, she reflected that You know, their goal was to keep students alive. And she said, if you’re an educator, that’s a horrible thing to have to have is your main goal. But she said it was really what they were feeling at the time in that very volatile climate.

DH: Well, one thing is certain. The issues may change, but it’s boots on the ground that actually make change. In fact it’s not just about PUSHING the envelope all the time. Soimetimes you have to stuff it first…

FITZ: My experience walking into Michigan was a little bit different than some of my peers. Because I had spent a year out of my senior year, January to January as an exchange student in Australia. And so I had viewed the tumultuous events of 1968. From the perspective of a foreign country, and not with the same kind of perspective, as a lot of my peers who had had seen the Democratic National Convention in Chicago had experienced the deaths of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy in slightly different ways than I had.

there were a lot of student protests, you can have a protest at a drop of a hat, that was an easy story to cover, there were they were very visual. And so when we we came to try to think of ideas for the the cover of our book, it was challenging, because they we did not have access to the same kinds of dramatic photographs. There were, there were no visible protests involving this, it really involved a lot of meetings and administrator sitting around a table and women, you know, who weren’t making pictures when they were stuffing envelopes in the middle of the night.

It’s interesting bringing up this point, I was thinking that by another book I wrote about the Republican political leader, Ellie Peterson, who was active in Michigan through the 1960s, and 70s. And she realized that women were providing a lot of the grunt work in the party, and felt that they were being taken for granted, they were the ones who were putting in the long hours of stuffing envelopes, and the foot soldiers and that sort of work. Jean King did the same sort of thing for the Democratic Party in the decade leading up to this complaint. And then there was the episode in my book, you’ll recall of when the women suddenly got the idea that if we want to communicate to campus women, let’s use the campus mail service, and they sat down and stuffed down envelopes, and using the staff directory, address them put this surge of mail into the system. And it wasn’t until the mail system administrators got curious as to what’s this surge of mail, that they yanked the letters and said, that’s a misuse of the university’s mail service, we’re not going to let you use it. But it was these little, as you said subversive kinds of things that women were willing to put in the time to do. And I’m thinking in our current environment, the number of my friends who are writing postcards for to backup candidates, and encourage people to vote. And they may be in a position where they can no longer feel they can go door to door and certainly in this COVID-19 era, there’s that is usually not going on in many parts of the country, but they found a way to be willing to take the time to do the kind of detail work that can make a difference.

Well, I’ll leave you with that sentiment. Even though the world feels chaotic in fall 2020, each one of us has power, and in exercising that power we can make the world a better place. OK, that’s it for now. See michigantoday.umich.edu for more episodes of Listen in Michigan and find us wherever you listen to podcasts. Stay safe and sane amid this global pandemic and — as always, Go Blue.

Paper chase

The word activism conjures a host of dramatic images. Many feature explosive conflicts as rage breaks through smoke and flame. Others are full-color visions of vitriol as protestors tangle with riot police. And then there’s that solitary warrior standing down a tank in Tiananmen Square.

Rarely does one’s imagination settle on the conference-room table, the literal anti-archetype of action, momentum, and social progress. But that’s exactly where one of the most significant movements in recent history took place. In her book, Conquering Heroines: How Women Fought Sex Bias at Michigan and Paved the Way for Title IX (University of Michigan Press, 2020), author and longtime journalist Sara Fitzgerald, BA ’73, describes a protest that took place mostly in secret, steeped in stealth, subversion, and, yes, mountains of paperwork.

“These women were not making pictures as they were stuffing envelopes in the middle of the night,” says the author, a former editor at The Washington Post.

The movement to confront sex bias on campus may have been wonkier than antiwar protests and boycotts on the Diag. “But as I began to work on it, I realized it did have suspense, and it was, in a little way, a thriller that had clandestine aspects to it,” Fitzgerald says.

Real life

It’s also a bit personal. As a Michigan Daily reporter assigned to the labor beat, Fitzgerald found herself covering a movement that would change her life and the lives of all university women. By graduation in 1973, she was thoroughly schooled in federal regulation and enforcement, a skill that would serve her well as a professional journalist in Washington, D.C.

The Daily gig evolved into the “sex discrimination beat,” and Fitzgerald followed the key players who set the stage for passage of Title IX legislation. Jean King, JD ’68, was a lawyer, Democratic activist, and mother, who once worked at the University. Kathleen Shortridge, MA ’70, was a graduate student in political science and journalism, who published an exposé in the Daily’s Sunday magazine that revealed gross inequities in hiring and admissions at U-M. And to a lesser extent, they found support from insider Barbara Newell, a protégé of then-President Robben Fleming, who was the only female VP in the administration (albeit, an acting one).

“There were a lot of things at stake, and some of the people involved were colorful characters,” Fitzgerald says, noting there were trust issues and personality conflicts along the way. “I felt it was a compelling story; I certainly felt that way when I was living through it.”

Alternate reality

The Education Amendments Act of 1972, which encompasses the law we know today as Title IX, protects people from discrimination based on sex in education programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance. It corrects a grievous omission in the historic civil rights legislation of 1964, which had excluded women in academia. For years, female scholars, administrators, staff, and students were not entitled to the same opportunities, salaries, and athletic facilities as their male counterparts.

One can only imagine how much worse life would have been for women at Michigan — and later throughout academia — if not for a spring 1970 meeting of the new Professional Women’s Caucus in New York. There, U-M’s King encountered Bernice Sandler, PhD, who explained how she had just sought legal recourse after being passed over for a promotion in her expanding department at the University of Maryland.

She had found a clause buried in the Presidential Executive Order 11375, issued two years after President Lyndon Johnson signed civil rights legislation that prohibited racial discrimination by federal contractors. Executive Order 11375 prohibited federal contractors from discriminating on the basis of sex.

“Sandler connected the dots that virtually every major university or college was a federal contractor,” says Fitzgerald. Now she had something tangible to work with.

Sandler and the Women’s Equity Action League filed the first sex discrimination complaint against the University of Maryland in January 1970, setting off an investigation by the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services).

King realized the strategy would likely work at Michigan since the University held the second-largest volume of federal contracts. She set about quietly enlisting support from friends and other U-M staffers. Shortridge, meanwhile, gathered additional documentation without raising red flags. All told, this material would anchor the May 1970 complaint to HEW filed by the Ann Arbor chapter of FOCUS on Equal Employment for Women.

So began an arduous and complicated legal journey as U-M and HEW parried back and forth for the next two years. King rallied her invisible network of well-placed secretaries to monitor and report on the administration’s response to the government. Many staffers copied and shared sensitive documents and correspondence that bolstered the women’s case.

These kinds of quiet, detail-oriented efforts resulted in multiple complaints at multiple universities, forcing a change in the environment that culminated in the Education Amendments Act of 1972. But the spoils have been a long time coming. U-M’s first and only female president, Mary Sue Coleman, was not appointed until 2002.

Decades later, Fitzgerald would access President Fleming’s papers at U-M’s Bentley Historical Library to read for herself the often-disparaging ways he and other university presidents dismissed the sex bias issue on their campuses.

“The memories still involved a lot of pain and anger,” Fitzgerald says of the female faculty members she met in the course of writing the book. “They’re happy the story has been captured, but I recognize that it was very difficult times for them.”

Not over yet

The federal government continues to respond to sex discrimination complaints on university campuses. In mid-October, Business Insider reported Princeton University will pay nearly $1 million in back pay and some $250,000 in future wages as part of a settlement agreement with the U.S. Department of Labor. Not surprisingly, Princeton admitted no liability and said it will make institutional changes, such as “conducting pay equity trainings for its employees.” Meanwhile, Yale University also recently adjusted the salaries of women who are teaching in its medical school. Both settlements were initiated by the Northeast Regional Office of the Office of Federal Contract Compliance at the U.S. Department of Labor.

“The problems still go on,” Fitzgerald says. “But clearly there’s a federal civil servant who’s continuing to ask questions and look at records.”

And while diving into records may not be a strategy that makes for dramatic protest photos, it’s an effective template that still works, Fitzgerald says.

“As we revisit this era and look at it with new eyes, we learn that our victories are built on the shoulders of women or leaders who went before us. And those are important lessons.”

Coreen Thompson (née Bohl) - 1985

I enjoyed reading this article championing the women who helped raise our daughters in a more equitable world. And speaking of women”who went before us,” I must inform you of a UM grad from the early 1960’s named Carolyn (Osborn) Bower who trained with the UM male gymnasts before there was any collegiate women’s gymnastics. I believe she was featured in an article (and on the cover?) of Sports Illustrated at some point and eventually became a founding mother of Big 10 Women’s Gymnastics. I know she was an Olympic judge for a while. She currently lives in Bowling Green, Ohio, but she owns and lives summers in an old family cottage on Crystal Lake in Beulah. I would love to read more about her influence and leadership in a field that is now dominated by women athletes (think Simone Biles!). Please let me know if I may share her contact information with you. She is still a vibrant and healthy woman despite her age and is filled with courageous and outrageous stories regarding her women’s rights journey.

Thanks for reminding us that equality takes time and that we must respect the work and sacrifice of those who’ve come before us!

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Thank you, Coreen! I would love to connect with Carolyn. My email is holdship@umich.edu.

Reply

Sara Fitzgerald - 1973

Carolyn would have attended Michigan back when the men’s gymnastics team did double-duty as the football cheerleaders, part of the tradition of not letting women walk on the floor of Michigan Stadium until Daily photographer Sara Krulwich challenged that rule in 1969. (Sara, one of my classmates, went on to win a special Tony Award for her photography of Broadway shows for the New York Times.

Reply

Carolyn Osborn Bowers - 1961 BS Edu MS The Ohio State University

Good story about the new women’s Chairman of the Department of Physical Education said they would drop me as a major if I did not stop training and competing. They would consider me an undesirable major. This came about because of an article in the Ann Arbor news following a national award as the most promising Woman gymnast 1956. Fortunately, when the dean of men heard about that, he told me he would take care of it, not to worry.

Reply

Sara Fitzgerald - 1973

After the Physical Education requirement was eliminated in the late 1960s, most women in the next few years could go through Michigan without having a single woman professor. One of the women who filed a sex discrimination grievance during this time was Joan Peters of the Physical Education Department. The federal government noted that at the time of her complaint, the department did not have a grievance procedure in place.

Diver Mickey King was another Michigan Olympian who trained without access to adequate facilities. I heard her describe them about nine years ago at a testimonial dinner for Jean King, who represented many women athletes in lawsuits involving Title IX and access to sports.

Reply