Full of contradictions

This month’s column is inspired by the responses I received to my July entry, “‘Do not breathe’ is not a good plan.” One reader thought I might be describing a framework that mayors could use to think about fire. It’s an interesting idea, and I’m going to write a series in the spirit of providing a framework for thinking about climate change.

The key, I believe, is to embrace a strategic mindset when considering the consequences of climate change. The goal is to develop an evidence-based and defensible approach to policy and practice. This requires both short- and long-term planning.

But climate change is complex and full of seeming contradictions that complicate our understanding. When an expert states climate change will make both drought and flood more likely and more extreme, some people dismiss the notion as scientists ascribing everything to climate change.

I realize many people want a simplistic message that will resonate, the one thing that climate change will mean to them. However, I ascribe to the rule that there is no one thing climate change will do. Complexity and uncertainty abound. If one decides to take on the challenge of climate change as meaningful and consequential, one also needs to get their heads (hands?) around that complexity.

We do this all the time: pursuing a career, planning our retirement, deciding whether to get a cat. I find that if I place climate change into a context of things we already know how to do, it becomes more manageable.

The beginning of the path

What we know best is that Earth has warmed, and we are on a trajectory of continued warming. The warming is uneven, meaning it varies from place to place, from day to night, from season to season, and from year to year. Scientific records and observations show the vast majority of Earth has seen a temperature increase.Unfortunately, we have not intervened adequately enough to decrease carbon dioxide or methane emissions, the proximate cause of the warming. Therefore, we can expect this warming to continue for decades to come. Coincidentally, the human capacity for planning maxes out in that same decadal time frame.

Carving a path

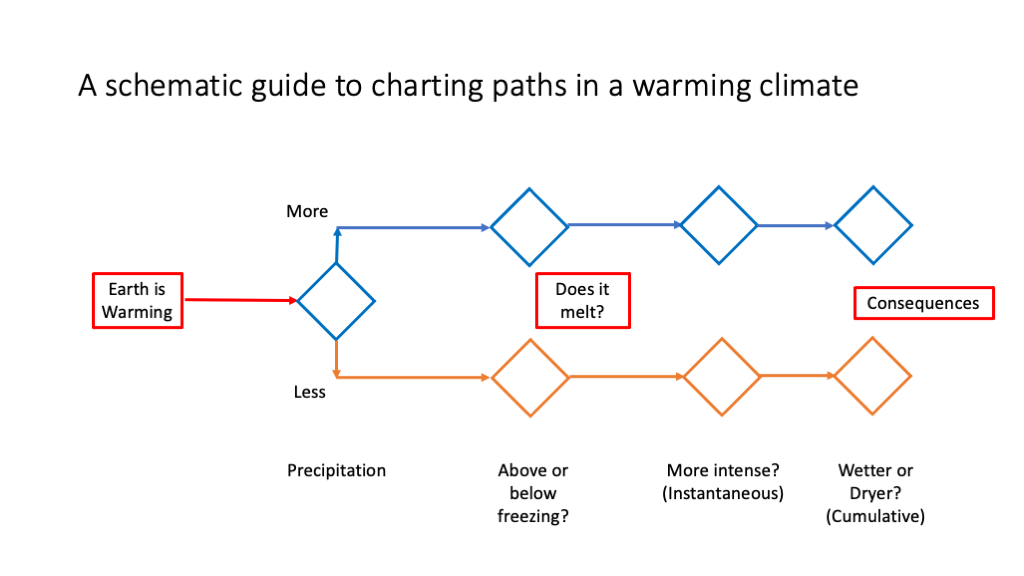

Temperature is the best-known aspect of climate change. It is also directional, and, on average, going up. Because we are so familiar with it, and we understand how things respond to temperature, I find it to be a good starting point when thinking about plausible paths to deal with climate change.

After temperature, we consider precipitation, i.e., water that falls from the sky in the form of rain, snow, and ice. And here’s where the complexity starts to grow. Increasing temperature can produce more precipitation and less precipitation.

First, consider more precipitation. With a rising temperature, evaporation increases from oceans, lakes, and the ground. Warmer air contains more moisture than cooler air. There is an important condition to note here: When water is present and available, warming leads to additional moisture in the atmosphere. Therefore, we reasonably expect storms to have more precipitation in the form of rain, snow, or ice.

The next thing to consider is whether the temperature is above or below freezing. The characteristics of atmospheric water droplets change in many ways at the point of freezing. With an increase in water vapor concentration due to warming, and cold enough temperatures to produce snow, it’s likely that huge amounts of snow will fall. Talk about a seeming contradiction: When the atmosphere gets warmer, snow intensity and accumulation can rise.

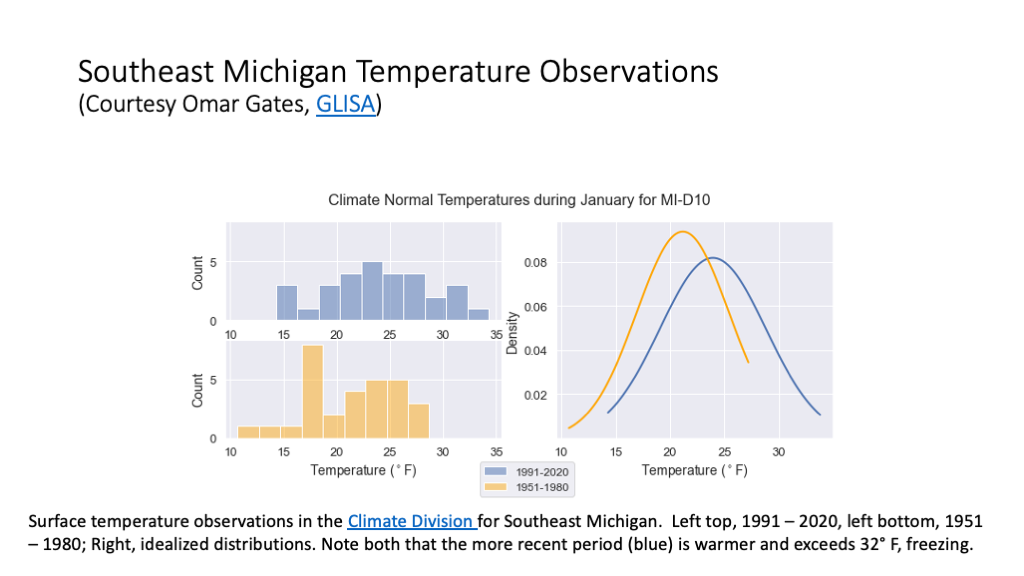

We expect changes in other forms of precipitation as well. Take freezing rain, which occurs near water’s freezing point. As temperatures rise, locations that log temperatures reliably below freezing can no longer make that claim. Therefore, historical snowy environments are more likely to experience rain and freezing rain. As the atmosphere grows warmer and warmer, frozen precipitation will mostly disappear altogether. The plot shows January temperatures in Southeast Michigan comparing 1951–1980 to 1991–2020. Aside from the atmosphere getting warmer, temperatures now regularly climb above freezing, 32° F. That is why I say we should expect more freezing rain in the winter months.

We expect changes in other forms of precipitation as well. Take freezing rain, which occurs near water’s freezing point. As temperatures rise, locations that log temperatures reliably below freezing can no longer make that claim. Therefore, historical snowy environments are more likely to experience rain and freezing rain. As the atmosphere grows warmer and warmer, frozen precipitation will mostly disappear altogether. The plot shows January temperatures in Southeast Michigan comparing 1951–1980 to 1991–2020. Aside from the atmosphere getting warmer, temperatures now regularly climb above freezing, 32° F. That is why I say we should expect more freezing rain in the winter months.

More strange possibilities

With more water in the atmosphere, we also can expect more extreme-precipitation events. Even so, these events are not an accurate indicator of how a season or a year will unfold. Will that extreme precipitation be felt as very intense rainfall over the course of a couple of minutes, or will it be felt as a massive amount of rain over the course of an entire day? A season? A year? Each scenario is possible, and given that historically we have experienced both, each is likely.

Now we’ve introduced yet another complicating factor as we consider the consequences of climate change. What are the cumulative effects, as opposed to the instantaneous ones? Or, on average, does our world become wetter or dryer?

Let’s pause to consider

I started down this path by idealizing a trend of persistent warming as a usable starting point to plan paths toward the future. From there, I went down a path that shows warming leads to more moisture in the atmosphere. Hence, future storms will feature more extreme precipitation. The nature of that precipitation could be solid or liquid, depending on the storm’s conditions. The total precipitation over the course of a year could increase, decrease, or stay the same.

The path I’ve been describing is conditional. Available water is required to evaporate and cause an increasing abundance of moisture in the atmosphere. But what if there is no water? With less precipitation present, the rising temperature will dry out the soil and vegetation. This path has less twists and turns than the other. Drought and its horrific consequences become more likely.

Contradictions

Once we follow the directional path about the consequences of increasing temperature, we must confront the ways in which water will change. In the future, will we experience more precipitation or less?

Most of us live in places that have historically experienced drought and flood, water scarcity and abundance. We should expect that to continue in the future; this is duality. As the climate warms, we are bound to experience effects that appear in opposition.

As we consider other questions on the paths of more or less precipitation, we confront even more forks in the road. The points where we face such dualities as wet-dry, frozen-liquid, and acute-chronic provide a multiplicity of outcomes. One of the only conclusions we can be confident about as we walk this path: Variability will increase, and we need strategies to address increased variability.

In my next column, I plan to explore the ways we think about and react to the instantaneous effects of one-off storms versus our response to the accumulated effects of persistent weather patterns.

Edward Proctor - 1966 MSME, 1983 MBA

As a Christian, I believe God is in ultimate control of earth’s climate, and He will determine when life ends on this planet. I also believe much of so-called “climate science” is based on human projections of temperature change and it’s relationship to CO2 concetrations in the atmosphere. I remember one of my Business School profs giving a warning about corralations in data. A study showed a strong corralation between the number of fireman sent to fight a fire and amount of damage caused by the fire. Like the study that shows a strong corralation between the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere and the temperature of the atmosphete. Q: does the sun have any affect on the temperature of the earth’s atmosphere? Is the radiant energy from the sun precisely uniform over time?

Reply

Richard Rood

Hi,

thanks for your comment. These are two serious questions. How are we supposed to interpret or act upon people’s differing religious views on climate and science in general? Second, if humans have curiosity and the ability to learn through science is not that something we should do? Don’t we have a responsibility to ourselves and others? I like to hear how people think about issues like this.

In my courses, I also teach about correlation and the “false cause” fallacy of saying correlation implies cause. That is why much of climate science is studying the cause and effect that leads to the correlations, and on seasonal time spans the anti-correlation, of CO2 and T.

https://openclimate.org/lecture-problem-solving-communications-logical-flaws-rhetoric-forms-of-argument/

As for the Sun … it is not strictly constant. It is the primary and dominant source of heat/energy for the planet. Without water and carbon dioxide Earth would be a frozen rock. So water vapor and carbon dioxide are essential to hold the solar heat near Earth’s surface. We are increasing carbon dioxide and methane, so we are heating up. We do account for the variation of the Sun in climate models.

In fact, my brother helped write a paper on this in 1977.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Syv6aE8yv3N0Ok4BFaVdJP9An7y3-7Bb/

r

Reply