‘Five hundred rowdies’

“Ann Arbor! Brain producer of Michigan, hide thy face in shame!”

So scolded Emma Goldman, the most famous radical of the day, after facing down a wild crowd of Michigan students on her lecture tour of the Midwest early in 1910.

Her subject was anarchism, the doctrine that opposes all government. Her listeners were ungovernable.

“Five hundred university rowdies in a hall, whistling, howling, pushing, yelling like escaped lunatics,” Goldman wrote of the experience. “How infinitely superior is the roughest element of workers, longshoremen, sailors, miners, street cleaners.

“I have addressed them all; been with them all; men with not enough knowledge to write their names… Yet all of them are as boarding-school girls compared with the university rowdies at Ann Arbor, who packed the hall to create a riot.”

‘The most dangerous woman in America’

Early in his tenure as director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover called Emma Goldman “the most dangerous woman in America.”

Born in 1869 to Orthodox Jewish parents, she moved with her family from Lithuania to Prussia, then czarist Russia, then the U.S., where her sister had settled in upstate New York.

Goldman devoured books; she defied her parents’ wish that she become a conventional wife and mother to work in a factory. She married, divorced, became fascinated by anarchism, and moved alone to New York City — all by the age of 20.

Soon she was writing and speaking on behalf of social revolution. She fell in love with a fellow anarchist, Alexander Berkman, with whom she planned the assassination of Henry Clay Frick, an industrialist known for brutal anti-labor tactics. Such a killing, the two believed, would constitute “propaganda of the deed,” spurring a worker revolt.

Frick survived. Berkman went to prison.

But Goldman, who was not charged, was launched on a writing and speaking career as America’s and Europe’s most notorious woman radical — “Red Emma” and “Queen of the Anarchists.” For the rest of her life, she would champion the causes of anarchism, labor, socialism, free love (for people of all sexual orientations), free speech, atheism, and birth control.

Emma vs. the police

President William McKinley’s assassin said he’d been inspired by a Goldman speech. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Labadie Collection.)

Charismatic and brilliant, Goldman provoked outrage among the conventional and admiration among the nonconforming. She was repeatedly arrested, banned, and vilified. President William McKinley’s assassin said he’d been inspired by a Goldman speech. Yet she also formed deep friendships and made her living, in part, as a midwife and nurse.

By 1906, Goldman had launched a publication of her own, Mother Earth, which published the work of intellectuals and artists from Friedrich Nietzche to Mary Wollstonecraft, mother of the author of Frankenstein. To raise money for the magazine, Goldman lectured across the U.S., and she made several trips to Michigan.

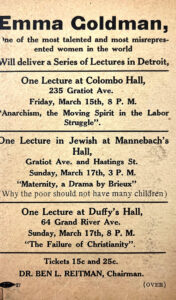

The warm-up for her Ann Arbor appearance in 1910 — apparently her first in the city — was a battle royal over her right to speak in Detroit.

Goldman was drawn to the state by her friendship with Robert Reitzel, a German-American writer in Detroit who had championed the free-speech rights of anarchists, including Goldman’s beloved Berkman.

With Berkman still in prison, Goldman met Reitzel in New York. She felt sexually attracted to him, and he to her, she wrote in her memoir. But her loyalty to Berkman quashed her temptation, and when she saw Reitzel next, in Detroit in 1910, he was dying of tuberculosis.

‘A desert of philistinism’

Goldman quickly found herself in the sort of free-speech fight that incited headlines for her cause and pulled audiences to her lectures.Her advance man in these years — as well as her sometime-lover — was a singular character and fellow radical named Ben Reitman, a physician who specialized in treating the itinerant class known as “hoboes.”

When Detroit’s police commissioner, Frank Croul, decreed that Goldman was not welcome at any lectern in the city, Reitman waged a publicity campaign that kicked up headlines for weeks.

In labor circles, Croul was decried as an autocrat. Progressives declared that Goldman’s speeches were worth hearing. One newspaper reported that “many prominent business men of radical ideas called on the commissioner personally and made known their views by telephone.”

Commissioner Croul backed down and Goldman spoke after all, at a German-American hall. After all the furor, her audiences were relatively small, perhaps because she chose less than incendiary topics — “Francisco Ferrer” (an anarchist educator in Spain) and “Love and Marriage.”

Of her stay in Detroit she soon wrote in Mother Earth: “Ridicule is a tremendous weapon against authority; thus Tsar Croul of Detroit may have come down from his throne for fear of appearing ridiculous.”

Detroit, she said, was “a desert of philistinism.” But that was nothing compared to Ann Arbor.

‘Pampered parasites’

Exactly when Goldman visited Ann Arbor in 1910 isn’t clear. It may have been while she waited for the ban in Detroit to be lifted. Or perhaps it was after she gave her lectures there.In any case, the headlines had charged up a college crowd ready to show her what they thought of her.

In the end, they got better than they gave. Surely no U-M crowd has ever endured a putdown quite as withering as Emma Goldman’s after that lecture.

“They stood down there and yelled and swore they’d slay me,” she wrote. “But for deeds, for deeds, there is not much of that in this town.

“These pampered parasites, not one of them with enough backbone to fight a flea; yet there they were yelling and screaming in true American fashion.

“My subject being anarchism, I needed no better argument against government than that living mass, nurtured and bred on law and authority, yet the first to break not only every human law, but every human law of toleration, kindness, and respect for the rights of others. These famous American chevaliers who revere women so much that their wild pushing and shoving endangered the lives of the women present; these defenders of property rights who demolished everything in the hall…

“The quality of these would-be students certainly speaks poorly for the professors. A course on behavior and decency would not be amiss at Ann Arbor.”

A regular visitor

Emma Goldman’s friend Agnes Inglis was the first curator of the Labadie Collection, which today holds Goldman’s archive. (Image: U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Still, members of a fraternity — she didn’t say which one — hosted her for dinner that night and couldn’t have been nicer. Several told Goldman they “felt deeply the disgraceful conduct of their colleagues at the meeting.”

She returned several times — in 1912, 1916, 1917, and 1918 — lecturing on anarchism, sex, art, revolution, Russian literature, and labor. She didn’t speak at the University; most of her talks were at the Woodman’s Hall at the corner of Main and Washington. In 1918, after she urged workingmen to resist the World War I draft, the city blocked Goldman from speaking.

She made at least one lifelong friend in Ann Arbor — Agnes Inglis, the unconventional daughter of a well-to-do Detroit family that feared Agnes would give her inheritance to radicals like Goldman. Inglis did make donations to support Mother Earth and helped Goldman to raise money for it. She became an anarchist and kept a scrapbook about Goldman.

The scrapbook and their correspondence are preserved in the Joseph A. Labadie Collection, one of the world’s leading compendia of social-protest materials, in the University’s Special Collections.

Inglis became the first curator of the Labadie Collection. Emma Goldman died in 1940.

Sources include the Emma Goldman scrapbook in the Agnes Inglis papers, Special Collections, University of Michigan; Emma Goldman, Living My Life (1931); Jacob Erhardt, “Robert Reitzel and the Haymarket Affair,” Yearbook of German-American Studies, 1987. Lead image comes from the Labadie Collection.

Rick Baum - 1986

Interesting writeup. Thanks for printing it.

Reply

Errol Shifman - 1978

While I certainly don’t agree with many of the things she was touting, if the heckling and destruction were as she described, she was absolutely right in her comments regarding human decency.

Reply

Eric Sullivan - 1998

Thank you for posting this fascinating story. It never occurred to me that Emma Goldman had been to Ann Arbor for a single speaking engagement, let alone several.

Reply

Karen Epstein - 1972

I don’t agree that anarchy is a solution. However, I agree strongly with Emma Goldman’s feminist ideas, some of which have yet to be realized.

Reply