The ground-breaking

In a light spring drizzle on May 23, 1952, Regent Roscoe O. Bonisteel turned over a spadeful of good farm topsoil just north of the Huron River. Next with the shovel came four deans, a professor, the Ann Arbor city council president, and a student, Howard Willens (1953), head of Michigan’s student legislature. Shutters clicked and dignitaries applauded. Construction of the University of Michigan’s most significant expansion since its founding had begun.

The regents decided to build North Campus not just to gain space to accommodate growth. They were signaling the University’s full embrace of research applied to the demands of an urban, industrial society.

As early as 1906, President James B. Angell had warned the campus was straining at its original boundaries. Pressures for growth only intensified with time. In 1932, President Alexander Grant Ruthven remarked that so many expected so much from higher education that a species of “super-university” was emerging, with Michigan a leading example.

“The university as an institution is rapidly becoming the brain of society,” Ruthven wrote. It must prepare students for worthwhile lives and develop new knowledge for a thriving industrial economy. Both missions were essential to “insuring the welfare of society.”

Bursting at the seams

Thousands of World War II veterans fueled the University’s need for more space. These two students of the 1940s posed against a backdrop of the farmland that would soon become the University’s North Campus. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Meanwhile, in the wake of World War I, Michigan’s leading industrialists (and influential engineering alumni in Chicago) began to press the College of Engineering for help. The regents agreed on a Department of Engineering Research (soon renamed the Engineering Research Institute). It would coordinate private research contracts to employ both faculty and students.

World War II brought a cascade of scientific and engineering research contracts to aid war industries and the military. And this was not research in a little glass beaker. It required heavy equipment housed in large buildings.

Peace brought crowds of returning servicemen funded by the federal “G.I. Bill.” Enrollment shot up to 22,000 students in 1948. That year, recalled student government president Blair Moody Jr., the campus was “literally bursting at its seams…with young men fresh from battlefields who desired a good education to enter the business world and recover years that they had contributed to their country.”

Before the war, most students traveled to Ann Arbor by train. Now, many more had cars and they needed parking spaces. And more were married, with children who needed play spaces. University planners tracked the sudden postwar “baby boom,” looked toward the 1960s, and knew campus growth was inevitable. But how?

A land-grant school like Michigan State could expand into its farm holdings. An urban campus like Columbia could grow by clearing nearby “slums.” No such options in Ann Arbor.

Three choices

Eero Saarinen, modernist designer of North Campus and the new home for what is now known as the School of Music, Theater, and Dance. (Image: Library of Congress.)

According to Frederick W. Mayer, a longtime U-M planner and author of the authoritative A Setting For Excellence: The Story of the Planning and Development of the Ann Arbor Campus of the University of Michigan, the leaders were considering three choices.

They could buy and demolish properties in the blocks west of State Street and north of Huron Street. That would wreck central Ann Arbor.

They could decide they just didn’t have the space for extensive research programs and drop them. That would wreck the University’s reputation.

Or they could buy land somewhere distant from the central campus. Only that choice made sense. But where?

The farms south of the University’s golf course? No, the cost would be too high. The old “Lower Town” neighborhood north of the Broadway Bridge? They’d have to tear down houses, and the land might flood.

How about the rolling farm fields that rose north of the Huron River? That seemed like a good place for students to study and live. The land was affordable, and it was only a mile from the center of the Diag.

Yes, that was it. So in 1949, the regents quietly bought 88 acres, then more, with an average price of less than $1,000 an acre. Within 10 years, the total land acquired would grow to 826 acres.

The designer

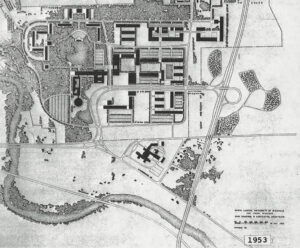

A portion of Saarinen’s 1953 master plan for North Campus. Note the expectation that U.S. 23 would run north/south along the campus’ eastern edge, with an interchange connecting directly to Bonisteel Boulevard. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

For plans, the regents aimed high and chose Eero Saarinen, son of Eliel Saarinen, a renowned Finnish-American architect who designed the Cranbrook Educational Community in suburban Detroit. The son had become even more renowned. Among many other buildings, including numerous corporate headquarters, he designed the modernist TWA Flight Center at John F. Kennedy International Airport, the main terminal at Washington Dulles International Airport, and the Gateway Arch in St. Louis. (He beat his father in the competition to design the Arch.)

Saarinen sent his first plan to the regents in the fall of 1951, a vision of roads (soon to be named for U-M regents), land use, and the placement of buildings in several groups — engineering, research, fine arts, natural resources, and housing.

Meanwhile, architects drew up blueprints. Within three years, four industrial research buildings rose along the new Bonisteel Boulevard — the Mortimer E. Cooley Building (named for a beloved College of Engineering dean); the Michigan Memorial Phoenix Project Laboratory with its attached Ford Nuclear Reactor; and the Automotive Engineering Laboratory, later named for Professor Walter E. Lay, who had initiated auto research at U-M. The exteriors were built of a modernist “North Campus Brick.” Four aeronautical/aerospace buildings quickly followed, plus married student housing, and a scattering of others.

The great migration

An early model arranged buildings in pods of connected blocks. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

But that was just the start. Through the 1950s, Saarinen directed an evolving series of master plans. As financial estimates shifted and professors weighed in with their preferences, the planners added, subtracted, and shifted buildings from place to place. The rolling landscape, with several stands of old trees, was largely preserved.

Saarinen’s early plans had arranged buildings in pavilions connected by covered passages. But try as it might, the University could never attract the massive funds needed to execute the architect’s vision in one grand sweep of coordinated construction. In the end, piecemeal funding drove a piecemeal construction strategy. But the Saarinen design for the property as a whole is still visible in the basic outlines of roads and land use.

Eventually, North Campus would accommodate a great migration from what came to be called “Central Campus.” The entire College of Engineering moved its operation there, as did the units that became the School of Music, Theater and Dance; the Stamps School of Art and Design; and the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning; plus libraries and a phalanx of residence halls and student support facilities.

Harlan H. Hatcher, who began his U-M presidency just before North Campus broke ground, remarked to the Michigan legislature: “It is a long road from the log cabin school in a clearing in the wilderness, the best the pioneers could do for their children, to the vast opportunities which we can now afford for ours — from the first small college hall to the intricate laboratories now required in engineering, medicine, and their supporting sciences. And it has been accomplished within the single lifespan of men now living.

(Sources include Michigan Alumnus, the Michigan Daily, and the book ‘A Setting For Excellence: The Story of the Planning and Development of the Ann Arbor Campus of the University of Michigan’ by Frederick W. Mayer. Lead image courtesy of the Michigan Daily Digital Archive, U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

Pamela Bernstein - 1980

I grew up in Ann Arbor and went to the University of Michigan in 1976. How disappointed I was when I learned my housing was out on North Campus. In reality, it was beautiful out there. I ended up transferring to the art school(a passion I had only entertained as a hobby) and ended up majoring in graphic and industrial design. I loved living out there for two years.

Reply

Dennis Hameister - 1973

I came to the UM in August 1969 & loved living on North Campus in Baits Housing. Spent my 4 years at UM in Baits & met my wife as she & her family were bringing her to North Campus. I spent 3 years on Housing Staff at Baits & met wonderful friends, with whom we stlll communicate with. After leaving Baits my wife & I lived in married housing over on Hubbard Rd. Great memories of good times in Baits Housing. GO BLUE

Reply

Allison MacDuffee - Ph D. 2004

My husband John and I lived in Family Housing on North Campus from 1996 to 2001. We enjoyed the lovely surroundings, the Wave Field by Maya Lin, the eclectic shops on Plymouth Road, and especially the friendships we made.

Reply

Martha Wallace - 1971

I was an out of state student, and I was not especially pleased to be assigned to Bursley Hall on North Campus. I had such a fine time there for two years and met my future husband during Orientation! Later, two of our children would attend U of M, one daughter was assigned to Bursley as well. Good times in Ann Arbor!

Reply

Michael Longo - 1985

Great article! As an Engineering Student in the early/ mid 80s I had to trek up to North Campus especially in my Junior and Senior years. Back then the Dow building and the Lurie Carillon Tower were relatively new. Now it’s teeming with new facilities including the ‘dude and research buildings.

Reply

Michael Evanoff - 1071

In my 3 years in Ann Arbor, North Campus might as well have been in the Upper Peninsula. All my classes were on the original and so-beautiful original campus. I loved it there and felt sorry for those who had been exiled to the North Campus gulag. I am pleased to learn that so many students enjoyed it out there!

Reply

David Steiner - 1977 LSA, BGS

Here is a little more history about North Campus that I thought you might find interesting.

Much of the North Campus farmland sold to the U of M was owned by my great uncle, Dr. Lloyd G. Steiner, U of M School of Medicine. He sold it to the U of M and brought property in Saline, MI. I don’t remember what year he graduated, but his picture is on a wall in a U of M hospital lobby somewhere. My father, Raymond, and his younger siblings (Richard, Wendel, and Cheryl) came to Ann Arbor in 1936 with their mother after the death of their father. Uncle Lloyd hired my father and uncles to help build a house for him near where the VA hospital now stands. The $200 he paid my father covered his tuition for the year when he enrolled for classes! Both of his brothers also attended the U of M after graduating from Ann Arbor High School, which was on the site of the present North Quad. Richard went on to graduate from the U of M Medical School. Wendel attended the Engineering college, but I think he was drafted before he could graduate. He went on to be a career officer in the USAF Strategic Air Command (SAC), finishing as a colonel. Until the early 1960’s, the farm’s barn was still on the site, just south of where the Art & Architecture building now stands. My dad got a photo of it before it was torn down.

Coming full circle, my father’s great grandson, and my great nephew, Raymond Shumaker, now a freshman in the U of M School of Engineering, attends classes, and lives on North Campus on land once owned by his great-great uncle, Dr. Lloyd Steiner. In addition, my twin brother, Richard, was the chief accountant for the U of M Plant Dept. for many years, overseeing the budgets for North Campus buildings and construction for many years.

Reply

Deborah Holdship

Thank you for adding to the story, David. So fascinating!

Reply

David Steiner - 1977 LSA, BGS

Deborah,

Are you the editor?

My brother had these comments/corrections regarding my piece.

I think the barn was actually across the street from the Gerald R. Ford Library.

To be 100% accurate my retirement title was Division Controller-Facilities Maintenance and Operations. I was not involved in construction, only maintenance, grounds, refuse/recycling, cleaning and utilities delivery.

Reply

David Burhenn - 1975, 1982 (Law)

Another great Jim Tobin story. While Saarinen is rightly credited with the overall design of North Campus, his firm was also responsible for one of the U’s modernist gems, the School of Music, Theatre and Dance (then, just the School of Music). This is unfortunately the only building that Saarinen designed for U-M but it remains (sensitively expanded) a real gem.

Reply