Football ticket fever

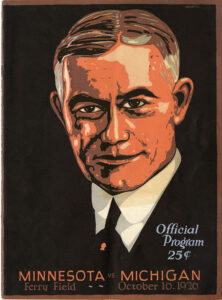

Yost was featured on the cover of a 1926 football program a year before the dedication of Michigan Stadium. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley HIstorical Library.)

A century ago, just like today, Americans were going nuts for college football. Colossal palaces had been built or planned at Yale (70,896 seats), Ohio State (75,000), and Illinois (92,000), among others.

In Ann Arbor, the crushing demand for tickets fell on the head of Fielding H. Yost.

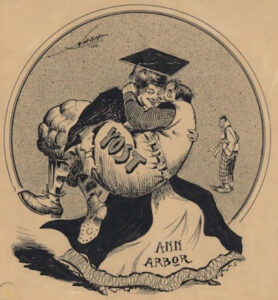

In Yost’s first years as football coach, 1901-05, his teams’ cumulative win-loss record had been 55 and 1 — so overwhelming that the Western Conference (forerunner of the Big Ten) passed rules to bring them down a peg. They left the conference, then returned in 1917. After a grim 3-4 season in 1919, Yost brought the Wolverines back to dominance.

Now past 50, he enjoyed a level of prestige in college football matched only by Notre Dame’s Knute Rockne. People said Yost could be elected governor of Michigan, if only he had wanted to run. But his ambitions remained in Ann Arbor. In 1921, he took on the duties of athletic director as well as coach. He made plans for a fieldhouse for basketball (soon to be named in his honor) and an intramural sports complex to fulfill his plans for “athletics for all.”

Still, football remained king. Home games at Michigan’s beloved Ferry Field were mobbed. On fall weekends, special trains discharged carloads of fans from across the Midwest, and Ann Arbor bedrooms were crammed with extra cots. The demand for seats was at least double Ferry’s capacity of 37,000. In 1922, half of Michigan’s entire student body attended the Ohio State game — in Columbus.But the regents said no to a brand new stadium — the cost would simply be too high. More stands were added at Ferry, but the demand only grew. When the Wolverines were named national champions in 1923, powerful alumni began to call for a new facility to seat up to 100,000 fans. Still the regents resisted.

“We owe a new stadium to the people”

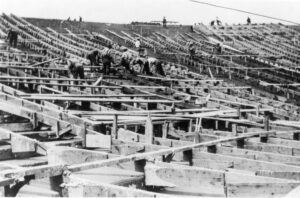

Yost even observed as seats were being numbered in 1927. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library. ) See a slideshow about the stadium construction.

But now Yost had an idea: To fund construction, he would sell 20-year bonds with two season tickets allotted to every person who bought a bond. No student fees. No donation drive. No taxes.

Alumni applauded. Students were ecstatic. President Marion LeRoy Burton liked the idea. It was sent up to the regents.

Then, early in 1925, President Burton died. His interim replacement, Alfred Henry Lloyd, professor of philosophy and dean of the graduate school, called a screeching halt to the stadium charge. He appointed a faculty committee led by Dean Edmund Ezra Day of the Business School and directed them to review the entire question of athletics at Michigan.

At this, Yost went into overdrive. All that spring and summer, he gave speeches to Rotary clubs, Kiwanis clubs, and chambers of commerce from Monroe to Marquette to Kalamazoo. Among outstate alumni and fans, he roused thousands of allies. He said Michigan was behind in the stadium race. The state had to compete. And more football revenue could advance the cause of “athletics for all.”

“We’re not after a new stadium simply because other stadiums have them,” he declared. “We owe a new stadium to the people who have every right to see Michigan teams in action. . . I call it plain, simple justice.”

Sites and specifications

Ann Arbor’s adoration of Yost was captured by a local cartoonist. (Yale’s famous coach, Amos Alonzo Stagg, looks on in envy.) (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley HIstorical Library.)

Meanwhile, Yost sent for blueprints of other stadiums. He especially admired the Los Angeles Coliseum, which was sunk into a giant excavation — it could never fall down. He wanted a rectangle, not an ellipse, so fans would see the action up close. He wanted the field laid out north and south, unlike Ferry, to keep the afternoon sun out of players’ eyes.

With engineers, he studied the land to the south and west of the campus. The state was already planning a big road (soon to be named Stadium Boulevard) to bypass downtown Ann Arbor on the south side of town. That could ease access for thousands of motoring fans.

Yost preferred to build on the University’s golf course, just south of the planned road. But his project engineer — Bernard Green, a U-M alumnus at Cleveland-based Osborn Engineering — noticed the ravine north of the planned road, in a parcel called the Miller Tract. Build the stadium there, he said, and the excavators would have less soil to remove. That tipped the choice of a site.

Early in 1926, the campus’s long wait for the Day Committee’s report ended. It was good news for Yost.

The members declared that Michigan should dampen the fierce emphasis on winning. After all, they said, the University was “an institution of higher learning, not a purveyor of popular entertainment. Intercollegiate athletics seem to have grown out of all proportion to the importance of the purposes which they serve.”But few people paid attention to any of that. Instead, headlines trumpeted the committee’s grudging admission that there might as well be a new stadium of perhaps 60,000 seats.

The regents approved and said that 70,000 seats, in fact, would be fine.

The biggest in the land

Steam pumps were required to remove water from a number of natural springs unearthed during excavation. Crews had to raise the level of the playing surface about six feet. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

The excavators hit unexpected water below the surface. But wells were dug to avert disastrous delays. Bond sales were slower than expected, but Yost threw himself into the selling. Crowds gathered every day to watch the construction.

On Oct. 1, 1927, with 72,000 seats, Michigan Stadium hosted its first game, a 33-0 victory against Ohio Wesleyan — though heavy rains kept the day’s attendance to under 40,000. The official dedication was held three weeks later on a fine Saturday afternoon when the Wolverines defeated Ohio State, 21-0.

Over the years many more seats were added — 13,752 in 1928; 12,187 in 1949; 3,762 in 1973; 1,500 in 1992; 5,000 in 1998; and (after 1,300 seats were lost in 2008), 3,700 in 2010. Today, with an official seating capacity of 107,601, it is the largest football stadium (college or otherwise) in the U.S.

Sources include Robert Soderstrom, The Big House: Fielding H. Yost and the Building of Michigan Stadium (2005) and The Michigan Daily.

Kendra Viola

I’m so confused. This article says Yost coached in the years 1901-1905. It outlines some accomplishments through 1920’s. Then it states, “In 1921, he took on the duties of athletic director as well as coach.” That is amazing that he was coach in 1901 and then, 120 years later, became the athletic director. How old did Yost live to be?

Reply

Deborah Holdship

I’m confused by your calculations. It was 20 years, not 120. Yost lived from April 30, 1871–August 20, 1946.

Reply

James Tobin - 1978, 1986

The story says 1901-1905 were his “first years” as coach, not his only years. He was football coach 1901-1923 and 1925-26. He was athletic director from 1921 to 1940.

Reply

steve carnevale - 1978

Thanks, Jim, for another brilliant, engaging article on the important history of Meeeechigan!

Reply

William Wilson

An interesting sidenote: Yost had the new stadium designed and built so that it could, at some point in the future, be expanded to seating capacity of 150,000

Reply

Michele Cross - 1967

My father often told us that he was part of the crew that worked on excavating the site for the U of M stadium. He was born in 1902 and lived in Fitchburg MA in 1924, but had moved to Royal Oak by 1928.

Reply

David Thoits - 1971

First touchdown was scored by M’s Kip Taylor. When I was an undergrad, old Kip ran the U’s golf course.

Reply