Unwittingly prescient

Last month, I wrote about an emerging pattern of floods. The takeaway: In a warming world full of oceans, any rain-producing storm is likely to produce extreme rainfall rates and record-breaking amounts of water. You can think of this as buckets that fill up fast, and there are a lot of buckets.

As I wrote that article, I did not anticipate the stunning floods in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia after Hurricane Helene. And, we can’t ignore the extreme rainfall rates in Saint Petersburg, Florida, with Hurricane Milton.

Trending now

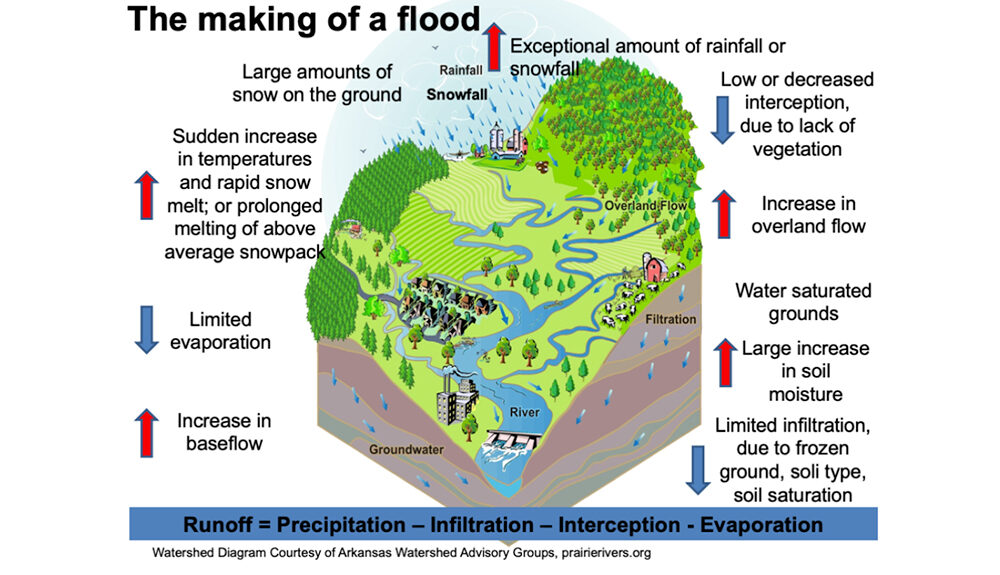

In the past year, I have written about flood scenarios several times. Floods are not just “a lot of rain,” and there are many ways to make a flood. If you’re attempting to understand floods, it’s critical you begin by evaluating the conditions on the surface. For example: Is there snow on the ground? Is the ground already saturated? Is there a lot of pavement? Are pipes funneling water to a particular place? The importance of surface conditions makes it difficult to make easy statements about whether or not climate change causes or contributes to increased flooding.One metric to analyze extreme rain events is the average recurrence interval. This measure is seen frequently in news stories, for example, the ‘1-in-100-year’ event. This term signifies that a certain magnitude in a specific area might be expected just once every hundred years. Another interpretation is that such an event has a 1% probability of occurring in any given year.

A 1-in-100-year event usually comes with severe consequences. Thus, an event that occurs once every 500 or 1,000 years wreaks even more havoc.

We do not have direct measurements of precipitation from 500 and 1,000 years ago. Therefore, when we talk about a 1-in-1,000-year event, we rely on statistical methods, backed up by our understanding of physical processes.

To the extreme

It is safe to conclude, that for most anyone, a 1-in-1,000-year event is unprecedented and unexperienced. It is also safe to conclude that few people, few regions, and few governments are prepared for such an event.

It is safe to conclude, that for most anyone, a 1-in-1,000-year event is unprecedented and unexperienced. It is also safe to conclude that few people, few regions, and few governments are prepared for such an event.

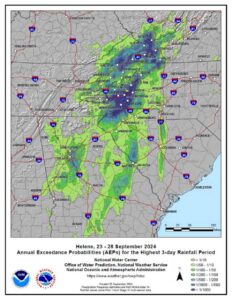

As context, for large portions of western North Carolina, the rain events in late September were more severe than a 1-in-1,000-year event. And earlier in the month, there was a much more localized 1-in-1,000-year event on the other end of the state. (Click on the image to enlarge.)

There is little doubt that when we experience a rain event that is as extreme as once in a hundred years, 500 years, or 1,000 years, we experience flooding. For a 1-in-1,000-year event, flooding will occur whether the landscape is urban, suburban, agricultural, forested, or wilderness.

For flooding associated with such extreme events, if we establish that these extreme events are occurring more frequently, then we can conclude there is a trend in flooding.

Observational evidence exists to support the increase in extreme events measured by average recurrence interval. For example, in the mid-Atlantic of the U.S., a 2022 paper concludes, “Collectively, the results indicate that, given recent trends in extreme rainfall, routine updates of extreme rainfall analyses are warranted on 20-year intervals.”

Take me home

Now, I return to North Carolina, my home state. I spent the first 20 years of my life traveling to nearly every part of North Carolina. The geographical extent of the September 2024 flood includes landscapes that are urban, suburban, agricultural, forested, or wilderness. All of it is in hilly and mountainous terrain that funnels water into ravines and canyons.

The amount of rain and the terrain’s subsequent focusing of that rain into torrents was landscape-changing. The ground liquifies and once we have a mud flow, rocks, roads, trucks, homes, and buildings are afloat. The pipes we designed to carry away water are, themselves, carried away.If this was really a 1-in-1,000-year flood, then maybe it’s wise to rebuild to incrementally higher codes and improved zoning.

But, with a warming climate can we count on our history that a flood like this will occur just once every thousand years?

In fact, we cannot.

We might expect a 1-in-1,000-year event to remain reasonably rare. But a person should expect to experience what had been a 1-in-100-year event several times in their life.

We need new language to describe these extreme events, which are no longer uncommon.

Repeating myself: The extreme weather we are experiencing today should no longer be considered extreme. We are only beginning to experience our warming climate. From a science-based perspective, it is safe to assume that today’s extremes are representative of what is emerging as routine.

Combating the conspiracies and chaos

The western North Carolina flood was immense and its consequences horrific. The story, however, does not end there.

It didn’t take long for the Pandora’s Box of conspiracy theories to break open. Disinformation ranged from accusations that meteorologists are controlling the weather under government direction to reports of the disaster being faked so that corrupt government officials could steal disaster relief money. These lies hinder response efforts and cause injury and damage to traumatized people. Though some misinformation may be rooted in legitimate fear and misunderstanding, many conspiracy theories are born of ill intent, and all are amplified with goals of discontent.

Aside from hindering rescue, relief, and reconstruction, the lies waste precious time. People, some whom I know well, spend valuable time — amid their devastated landscapes and disrupted lives — reporting and refuting conspiracy theories that are flat-out lies.I believe that our biggest threats from climate change are rooted in our own response to what is unfolding. What policies are in place to limit warming? How do our local and national leaders react to weather catastrophes? How do our governments anticipate and prepare for future weather catastrophes? How do we rebuild after the fact?

If we allow lies, the undermining of our institutions, and the dismissal of science-based evidence to rule the day, it only supports my belief that we are the greatest threat to ourselves. To be effective going forward, we need behavior and practice that is organized, connected, and broad-reaching.

Lawrence Gagnon - 1968 1976

Excellent article. Would be even better if a few sentences were added elaborating on connection between warming of planet and increased rainfall. A subsequent article might address the potential benefit of remedial actions by the U.S. without corresponding actions by other highly populated countries.

Reply

Abigail Welborn - 2004 LSA

His article here talks about some of the association between floods and warming: https://michigantoday.umich.edu/2024/09/20/i-feel-the-earth-squish-under-my-feet/

But I, too, would be interested in knowing how much one country can do unilaterally. Do you think a large country taking the threat seriously would motivate others?

Reply

Chris Campbell - 1972 (Rackham); 1975 (Law)

How can we learn from experience when attention is diverted to correcting false information? During the pandemic my clients often reported experiences with Covid. I’d inquire if they had been vaccinated. Often the response was “Oh no, it’s not safe, I’ve done my research.” That “research” was usually a trip to the internet’s unmoderated quarters.

Reply

Abigail Welborn - 2004 LSA

That’s a great connection to make. I loved this thread as a sort of “post-mortem” about Covid (mis)communication. https://yourlocalepidemiologist.substack.com/s/yle-health-miscommunication

My biggest takeaways were: 1. make sure scientists are clear about the difference between what the data say and what they infer/recommend because of it, and 2. get out in front of mis- and disinformation by proactively communicating. In this case, maybe telling people in advance “Here’s where you can go to collect immediate aid, here’s where you apply to long-term aid.” There’s a risk of diverting people away from preparing and evacuating, but then you’ve also prepped people who weren’t told to expect a flood because Helene was worse than predicted (e.g., a lot of people in North Carolina), who will then remember “oh right, there are two kinds of aid,” etc.

But you’ve got me on how to convince people no one is building hurricanes on purpose.

Reply

Susan Roaf - 1975

Great article – demonstrating the need to ‘Bounce forwards not backwards – with as you say – resilient reinstating of system – upgrading them for worse future climates. I think you may like to join us at our comfort at the extremes conferences – we need some reality checks like everyone else. I think people really never thought of accelerated pluvial extremes in the climate – just look what happened after the last Ice Age….

Reply

Jonathan Blanton - 1975

Good article with important advice that we need to prepare for the effects of climate warming, which includes hardening and upgrading our infrastructure of all types and our public and private property. I must say though that dignifying and crediting ridiculous conspiracy theories by inclusion in the article implies way more importance and influence than they actually have. I recommend ignoring such nonsense which has always been part of the human condition in these situations. The vast majority of people pay it no mind and use common sense and credible evidence.

Reply