So much for effective interventions

In 2007, in one of my earliest articles on climate change, I wrote about the relocation of an Alaskan village that was falling into the sea. I wondered whether we required such catastrophes to happen. Or could we intervene, reduce emissions, and prevent them?

Being a rational incrementalist with confidence in institutions, I believed we could carry out effective interventions.

Life has, however, taught me otherwise. Catastrophes are required.

Embracing catastrophe

Disruptive events and abrupt changes are part of life. Sometimes, we even construct them. In my most recent column, I wrote that ongoing crises — to our security, economy, health, or energy — make it difficult for us to prioritize the crisis of climate change.

Not all abrupt changes are disasters. The transformation of liquid water to ice is an abrupt change that occurs at a particular temperature. In weather, we experience abrupt changes at fronts that separate hot and cold air. These changes are natural and predictable.

Another abrupt change we might recognize is the bat hitting a baseball. This is described as an impulse.

Abrupt changes are common enough that we have a way to describe and model them in physics and mathematics: Catastrophe theory is the study of discontinuous transitions.

Catastrophe theory is well developed in social science, where abrupt transitions in politics and societies rule the day.

The innovator’s dilemma

One of my coveted management books is The Innovator’s Dilemma. It was written about businesses that have a successful product — until a new disruptive technology or product comes along. Examples would include how we listen to music or watch movies. We go from live events, to acetate or vinyl recordings, to tapes, to CDs, to streaming. The computer industry includes hundreds of examples.

If you have a strong and profitable customer base with one technology, how do you manage the onset of a new technology? Many large businesses fail, with a remnant of the old technology holding on in a much smaller market. There is a fascinating piece of land not far from me plotted out in open fields with street names like Tape Drive, Memory Lane, and Disk Drive. It comes from a company named StorageTek, when robotic tape storage was at its peak a couple of decades ago.

We all face this challenge — doing what we’ve always done, which might be very successful, versus changing to something new. We perceive the new way as far too risky. We don’t see that the actual risk is our own catastrophic failure in the wake of this innovation.

Those who succeed at such transition points push forth new solutions, rethink what they have been doing. Many old thinkers are replaced with new thinkers who embark on paths leading to their own eventual innovator’s dilemma.

Climate disasters

I started this column with a reference to a 2007 climate disaster. It was a climate disaster because the sea ice that protected the coast had melted and the coastline was opened to erosion. Since then, we can count many weather-related disasters amplified by a warming climate.

It is natural that we would take a wait-and-see approach to observe how disruptive a warming climate might be. Therefore, it does not surprise me that we require a series of disasters to act, perhaps, a series of more severe disasters. Unfortunately, we think we can bandage things up and carry on — it is the natural thing for most of us to do.

I call this “protect and persist” and view it as one of the many behavioral barriers we must overcome to cope with a warming climate. I got to talk about this at the 2021 Biennale di Venezia, a meeting of architects.

Protect and persist is not only natural, but also what our behavior, policies, and practices encourage. We will rebuild on the lot that we own, which is likely home, right where the devastating hurricane or fire just took our house.

Though I would like to think we do not require repeated disasters to break this cycle, I see little evidence of that happening in our risk-averse population. More of us are vested in the status quo, or even the past, than we are in innovative solutions.

Climate change is the easy part

The psychological, behavioral, and political challenges that come with the changing climate are far more difficult to face than the scientific and technical challenges.The prospects that we would address climate change as a nation, as the world, plummeted with the 2024 U.S. Presidential election.

This had been coming, as we have spent more than 30 years with larger and larger swings between addressing and not addressing climate change.

But in the year 2024 — and now 2025 — we have arrived at a critical moment. From a climate policy perspective, it is a catastrophe.

And catastrophes are handled by innovative thinking and new ideas.

For many years, I have felt that our community’s primary approach to addressing climate change was a prescription for disaster. That approach states that we have until 2030 or 2040 to reduce emissions by some large percentage to avoid the worst effects of climate change. To that we add, “and we still have time.”

I got to talk about this at the National Science Foundation in 2022, and I extracted a short video that interpreted our messaging, crudely perhaps, as catastrophe theory.

The basic idea was that extreme, rapid reduction of carbon dioxide emissions requires disruption of our energy acquisition. Such a transition directly assaults the power and wealth structure of corporations and nations. There is no reason to expect the scientific evidence of climate change to motivate an orderly transition.

Indeed, a rapid transition to renewables would be catastrophic to these corporations and nations. As they hold wealth and power, they will not let that happen, and it is unrealistic to expect them to let that happen.

The unsatisfying present

We now arrive at a moment that is perilous for the climate. It is even more perilous for science and society.The already weak words of trying to manage greenhouse gas emissions and limit warming will disappear as we exit the Paris Agreement. We are promised deconstruction of basic scientific capacity held by or funded by the U.S. government. Energy policy will swing to set up barriers to the market forces that have been increasingly driving the renewable energy transition. The hubris that we can manage our climate through global environmental engineering will grow.

And the climate will continue to become warmer.

Though we have experienced meaningful progress in addressing climate change, it is evident that our collective efforts have not been especially effective. Therefore, we need a better approach than “protect and persist.”

Those who grow and thrive after a catastrophe are innovative in their adaptation. In a world so rapidly changing, whether it be our climate, our technology, or our government, the complacency of the innovator’s dilemma must be avoided.

The idea that we will achieve smooth societal transitions based on scientific evidence is foolishness.

Catastrophes will occur. They are required. And we must strive to cross them successfully.

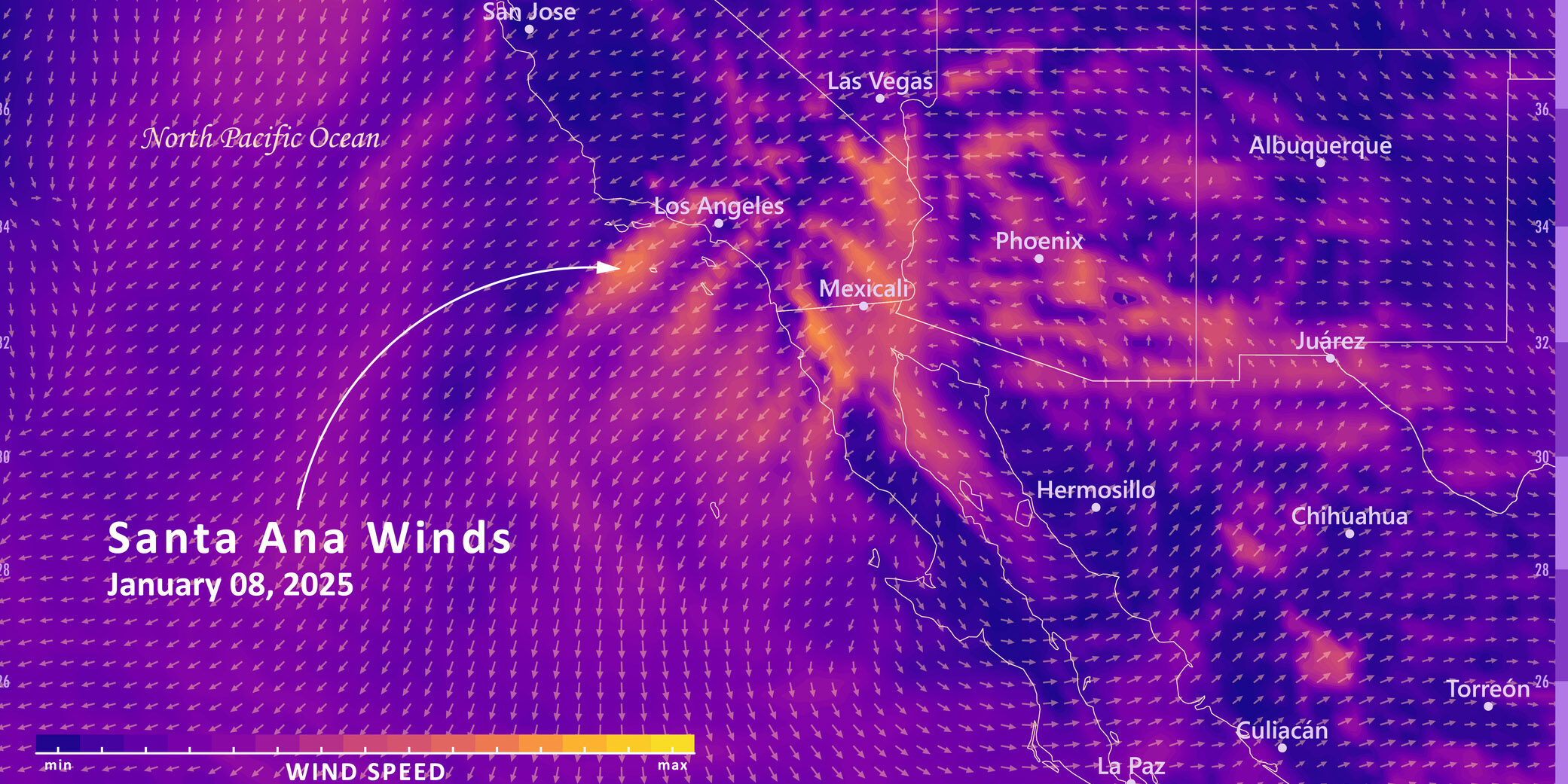

(Lead image: Wind Speed Weather Map of the strong Santa Ana Winds at Los Angeles County on Jan. 08, 2025. Made with data from Global Forecast System GFS. All source data is in the public domain. Wind Speed data: NCEP GFS 0.25 Degree Global Forecast Grids Historical Archive. Countries and Boundaries: Made with Natural Earth. Credit: iStock.)

David Kochalko - ‘75, ‘78, ‘82

For a “better approach” start with honesty and integrity. Since this article features a photo from the (still burning) LA fires, you have an opportunity to write one dedicated to the man-made factors which led to the devastation of those communities. Including that photo in this piece by association implies climate as the cause. Nothing is further from the truth in this case, the scale of damage from the fires in LA is a failure of public policy and not evidence of climate change.

Reply

Richard Rood

Please consider this

https://openclimate.org/wildfire-collection/

It includes several Climate Blue articles on wildfire.

Then we can talk about distance from the truth.

I believe, in any circumstance, the LA fires are a disaster, a catastrophe, which is the subject of this entry.

Reply

Norb Roobaert - 1963

There is much that has been written and discussed about global warming now usually called climate change.

Despite all the talk, writings, lectures, accords, summits and money spent on addressing the issue not any noticeable progress has been made.

The only things we’ve been able to do with some good results is adjust. LA did not plan or act to be ready.

Reply

Jonathan Blanton - 1975

The primary cause of the LA wildfire catastrophe is foolish and irrational public policy, not climate change. Cycles of extreme drought and heat have been occurring for centuries in California, some worse than in modern times, and lowering man made emissions to whatever level will not change that, nor would it prevent these fires. Ironically, these policies have been promulgated by climate activists and environmentalists together with their Democrat allies and along with governmental incompetence, created this perfect firestorm. Hopefully, after the 2024 election we can move in a more sensible direction, but I’m not holding my breath given the California electorate which is infamous for making bad voting decisions.

Reply

Richard Roood

WIth regard to the comments above.

First, this article was not about fires.

Second, nothing I have written has said that fires were “caused” by climate change. In the link I provided in the first comment,

https://openclimate.org/wildfire-collection/ ,

in the beginning, I summarize the roles of landscape management and a warming climate, so that no one has to read thousands of words. With the exception that the commenters chose to take an on/off, black/white, sometimes political point of view, I don’t think what I have written stands in opposition to most of the points about landscape management that they have made.

Third, a little thought problem.

I think in this group we might agree that the climate is getting warmer. We might agree that weather has an important role in wildfire (dry fuel and wind, being the most important). We agree on the past, present, and future of drought-flood cycles. We agree, I think, on the importance of excess dry vegetation (fuel). We can probably agree on the connection between drought-flood cycles and vegetation growth and drying. With the climate getting warmer, it must change the drought-flood cycle and vegetation growth-decay cycle in important ways, because we really can’t add energy to the system and expect no change can we? Therefore, fire conditions have to change, right?

Fourth,

“Hopefully, after the 2024 election we can move in a more sensible direction,” at some level that was the point of my article.

Finally, it is possible to make a point without suggesting that I am dishonest and lack integrity.

Reply

Norb Roobaert - 1963

Professor Rood: I have carefully reread your article. I agree with your comments above. I have tried to determine what your point is and conclude the following:

1) we cannot as a practical matter be innovative to prevent catastrophes because corporations and nations would lose profits. Question: what about the people?

2) Rapid reduction in CO2 emissions requires displacement of energy acquisition. Question: How do you think this can be done?

3) I think we have to be practical and do what can be done to minimize the damage. Houses in Galveston on piles and constructed for hurricane winds. Forest maintenance, brush removal and adequate water supply in LA. Not rocket science.

Reply

Richard Rood

Hi,

thank you for the note and rereading.

1) We can be innovative to prevent some catastrophes through adaptation policy and practice. I believe part of being innovative is to focus on near-term, local-scale problems that are important. The longer mitigation problem is tough, and I think the current state of the world, not just the US, is making it tougher. It disturbs me that the public discourse / press often distracts and dilutes what is important for getting things done. I don’t have any innovative answers, or rather, I don’t have any ability to move any forward.

2) I think, at best, the changes of energy acquisition is a decades long process. Since 2007, one of the basic conclusions from my class is that we must learn to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

3) I agree … I have been writing about adaptation for years. We can’t keep building in some places. I owned a house near the water in Maryland that lost much of its value because of rising ground water. When I discovered this, as I was trying to sell it, I found out that several houses in the neighborhood were in the same situation. There was a brisk business of 100K improvements to lift the (small) houses about 12 inches. This might last a few years, but it is not sustainable. I sold for probably 25% of what it was worth 12 months earlier. Some people in the area are starting to use stilts. Little 1/8 acre lots. A decision that I can make, but what is the public policy of managing this.

And as a point, on this level this is not a Democrat versus Republican problem. All were involved in getting where we are at, and all are interested in what to do.

Again, thanks for the comment.

Reply

Sari Sommarstrom - 1973, 1976

Let’s look at credible studies about how much climate change contributed to the LA winter wildfires. A research group found that climate change made Southern California’s dangerous wildfire conditions in early January 35% more likely than they would have been before the industrial era. Here’s one from UCLA:

https://sustainablela.ucla.edu/2025lawildfires The combination of fire conditions on Jan. 7th in LA were extremely unusual, only waiting for human-caused triggers to ignite. Nothing can defeat flames in 80-100 mph winds.

Promoting a political blame game does not help while we wait a full objective assessment of this catastrophe. Living in California, where everyone in my extended family has had to evacuate at least once in the past 5 years, the chronic fear of personal and community wildfire catastrophe is very real. Farmers acknowledge that droughts are becoming more frequent and the weather is warmer, yet they don’t like to say “climate change” as the term is too politically charged. And most people feel powerless to do anything to help.

Rebuilding will partially happen, with better building codes and landscaping. Water system infrastructure at a capacity to fight fires under extreme conditions may be unaffordable. But it is a losing battle in SoCal’s climate and dense population.

Reply