Allergic to water

So, here I was playing golf with a friend. It was hot. We were both sweating. So I poured water inside my hat and turned the hat over my head and face to cool down. I offered my friend water from my bottle so he could do the same. He refused and said, “I’m allergic to water.”

“WHAT!” I screamed. “How can you be allergic to water?”

As he wiped the sweat from his face, he replied: “I have a rare disease.”

He told me that as a child he would have meltdowns (no pun intended) every time he was forced to take a bath. He would yell, scream, and cry. He told his parents the water hurt his skin, and it was unbearable. They didn’t believe him and continually forced him into the bath. He said it was a nightmare.

When he was much older, a doctor finally diagnosed his condition. Aquagenic Urticaria (water allergy) is an extremely rare disease that manifests when water interacts with skin. With aquagenic urticaria, a person’s skin turns red and itchy after overexposure to any amount of water, snow, sweat, or rain. Often, the associated pain includes an extreme burning and prickly feeling.

I returned home, took a shower (oh boy, I felt guilty), and looked up aquagenic urticaria. My deep dive revealed other rare diseases I’d never heard of.

A little history

Before the 19th century, the understanding of diseases was mostly empirical. Many conditions, especially those with obscure or unusual symptoms, went unnoticed. At the time, people believed most diseases were caused by divine punishment, evil spirits, or environmental factors.

In this medical school clinic in 1893, faculty and students examine a body. (Image courtesy of U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.)

It wasn’t until the late-18th and early-19th centuries, during the Age of Enlightenment and the rise of scientific medicine, that the study of diseases expanded. Advances in anatomy, pathology, and clinical observation helped scientists identify diseases in a more structured way. It was in this period that doctores were first able to document many rare diseases.

During the 20th century, as medical classifications and epidemiological studies became more sophisticated, the concept of a “rare disease” began to take shape. The first disease classified as rare was Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS), often referred to simply as Progeria or Progeroid syndromes (PS). The English surgeon Dr. H. Gilford is credited with naming the condition. He first described it in 1886, and again in 1904. Progeria comes from the Greek words pro, meaning “before” or “premature,” and geras, meaning “old age.” Progeroid syndromes are a group of diseases that cause individuals to age faster than usual. Progeria is sometimes referred to as “Benjamin Button disease,” named after F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1922 short story and the 2008 movie “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.”

However, in terms of written records, one of the earliest and most famous rare diseases is Morphea, first described in 1867 by Sir Erasmus Wilson, a pioneer in the new field of dermatology. The word morphea comes from the Greek word forma, which means “spot of the skin.” Morphea is a rare, localized skin condition and is now classified as a form of Scleroderma (an autoimmune disease) that mainly involves isolated patches of hardened skin on the face, hands, and feet (or anywhere else on the body). Internal organs are rarely involved.

Other early descriptions of rare diseases emerged from isolated case reports, rather than widespread recognition of a specific medical disorder. The classification of rare diseases and the increasing understanding of their genetic, environmental, and molecular causes has increased dramatically, thanks to progress in genetics, molecular biology, and biotechnology. Patients now receive better care and researchers have more focused avenues of inquiry. However, we still encounter “orphan diseases” that are so rare it is difficult to generate funding or research to study them.

What classifies as a rare disease?

In the United States, a disease — assuming it has been cataloged — is classified as rare if it affects not more than one person per 200,000 Americans. Other countries apply different standards. For example, the European Union defines a rare disease if it affects not more than one person per 2,000 in the European population. The average time it takes to get a diagnosis for a rare disease is five to seven years, and it can involve up to eight physicians and three misdiagnoses.

How many Americans have a rare disease?

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), there are approximately 7,000 rare diseases affecting between 25-30 million Americans. This equates to one in 10 Americans, or one on every elevator and four on every bus.

How many rare diseases are there?

The National Organization for Rare Disorders offers a database of approximately 1,300 reports on specific diseases written in patient-friendly language on its website, www.rarediseases.org. The most complete listing of rare diseases in the U.S. resides on the NIH Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center website.

Rare diseases are present across the medical spectrum. Some are widely recognized by name, such as cystic fibrosis (a genetic disease that causes the body to produce thick, sticky mucus that can lead to breathing and digestion problems). Most cancers (all but a few types) are classified as rare. Other rare diseases are less known, such as Cat Eye Syndrome, a rare chromosome disorder, usually diagnosed in children. It tends to appear as a hole in the iris below the pupil, resulting in the appearance of a cat’s eye.

There are rare neurological and neuromuscular diseases, metabolic diseases, chromosomal disorders, skin diseases, bone and skeletal disorders, and rare diseases affecting the heart, blood, lungs, kidneys, and other body organs and systems. Many rare diseases are named for the person or persons who first identified them. A few are named for patients, like Lou Gehrig (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease. Sometimes the diseases are named for the hospital where they were identified: Floating-Harbor Syndrome was named after the Boston Floating Hospital and Harbor General Hospital in Torrance, California. It’s an extremely rare genetic disorder characterized by a distinctive facial appearance, various skeletal malformations, delayed bone age, and expressive and receptive language delays.

Problems for people with rare diseases

Aside from suffering symptoms of the disease itself, individuals with a rare disease also experience other difficulties. Since so little is known about certain diseases, obtaining an accurate diagnosis can take years. Most doctors know little about any of the 7,000 or so rare diseases. Hence, they generally misdiagnose the disease and prescribe treatments that do not help or, in some cases, actually harm patients. Even if the disease is correctly diagnosed, patients often have limited treatment options.Pharmaceutical companies have virtually no incentive to develop drugs or other treatment options for the small population that may be afflicted by a rare disease. The time it takes to bring a new drug to market typically takes 10-15 years or more. The process of developing a new drug involves research, discovery, preclinical development, clinical trials, and finally, FDA approval. Only about 12% of drug candidates successfully make it through clinical trials and approval by the FDA. On average, the cost to bring a new drug to market averages from about $43.4 million to $4.2 billion.

Of the 7,000 known rare diseases, approximately 95% have no treatment options. Often patients receive “off-label” treatments that are not approved by the FDA for the specific disease. This can lead to problems with insurance reimbursement, not to mention treatment failure.

Various governmental and nonprofit organizations have promoted grants to develop drugs to treat rare diseases. For example, the FDA’s Orphan Products Grants Program funds research and clinical trials for a host of rare diseases. At this time, the FDA also oversees other grant programs, including the Rare Neurodegenerative Disease Grants Program and the Pediatric Device Consortia Grants Program. The Orphan Disease Center offers over 50 grant opportunities each year for research on rare diseases. Despite these efforts, orphan disease funding remains a deterrence to successful drug treatment production.

The rarest diseases

Of course, there is controversy regarding what are the rarest of rare diseases. While rare disease diagnoses are difficult, and reliable reporting is mostly absent in the literature, it is difficult to rank the rarest of rare diseases. Here are few:

Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase deficiency

RIPD causes muscle stiffness, seizures, and reduction of white matter in the brain. To date, there are only four known cases, all diagnosed between 1984-2019.

Field’s disease

This progressive neuromuscular disorder causes degeneration of muscles and body weakening, involuntary muscle movements such as hand trembling, and persistent and painful muscle spasms worsened by emotional distress. Welsh identical twins are two of only three people known to have been affected.

Progeroid syndromes

This group of rare genetic disorders mimics physiological aging, making affected individuals appear to be older than they are. Even 2-year-olds look aged and weak.

Methemoglobinemia

Symptoms include headache, dizziness, shortness of breath, nausea, poor muscle coordination, and blue-colored skin (cyanosis) caused by elevated blood methemoglobin (a form of hemoglobin that makes blood blue). Complications include seizures and heart arrhythmias.

Foreign Accent Syndrome

In this rare neuropsychiatric condition, which results from a stroke, individuals develop speech patterns that are perceived as a foreign accent that deviates from their native accent without having acquired it in the perceived accent’s place of origin.

Harlequin Syndrome

This condition is characterized by asymmetric sweating and flushing precipitated by intense emotions, heat, or exercise on the upper thoracic region of the chest, neck, and face. One side looks pale, dry, and cold to the touch, while the other appears flushed, with large amounts of sweat. These two sides of the face are sharply demarcated at midline, resembling the Italian theatre character Harlequin, hence, the disease’s name.

References

- Angelis, A., et al. “Socio-economic burden of rare diseases: A systematic review of cost of illness evidence.” Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2015;119(7):964.

- Ehrhart, F., et al. “A resource to explore the discovery of rare diseases and their causative genes.” Scientific Data, 2021;8:124.

- Fagnan, D.E., et al. “Financing drug discovery for orphan diseases.” Drug Discovery Today, 2014:19(5);533.

- Ferreira, C.R. “The burden of rare diseases.” The American Journal of Medical Genetics, 2019;179(6):885.

- Forman, J., et al. “The need for worldwide policy and action plans for rare diseases.” International Conference for Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs (ICORD). Acta Paediatrica, 2012;101(8):805.

- Haendel, M., et al. “How many rare diseases are there?” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2020;19(2):77.

- Moynihan, B. “The making of a disease: Female sexual dysfunction.” The BMJ, 2003;326.

- Moynihan, R., et al. “Selling sickness: The pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering.” The BMJ, 2002;324:886.

- Roessler, H.I., et al. “Drug repurposing for rare diseases.” Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 2021;42(4):255.

- Smith, R. “In search of ‘non-disease.'” The BMJ, 2002;324:883.

- Tambuyzer, E., et al. “Therapies for rare diseases: Therapeutic modalities, progress and challenges ahead.” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2020;19(2):93.

- Tambuyzer, E. “Rare diseases, orphan drugs and their regulation: Questions and misconceptions.” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2010;9(12):921.

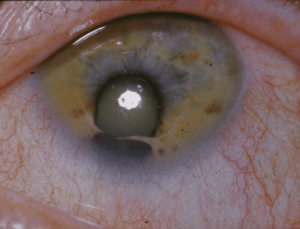

(Lead image of aquagenic urticaria courtesy of drhealthclinic.com.)

Lawrence Stiffman - 1979 umsph

Is permphigus vulgari, an auto immune disease, too common to be included on a rarity list?

Dr Anhold (a mich med grad) assisted my mother at Johns Hopkins. Epidemiologic leads to at-risk groups such as Eastern European Jews and male butchers.

Reply

Victor Katch

There are several types of pemphigus, but the two main ones are:

* Pemphigus vulgaris, which normally affects the mucous membranes, such as the inside of the mouth, genitalia and skin.

* Pemphigus foliaceus, which only affects the skin.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is often considered a rare autoimmune disease, depending on what classification you use. It occurs in about 1 to 5 people per million worldwide each year. The incidence of PV varies by location and ethnicity. It’s more common in Ashkenazi Jews, people of Indian origin, and people from Southeast Europe and the Middle East. It occurs more often people between the ages of 30 and 60.

In Pemphigus the immune system mistakenly attacks cells in the top layer of the skin (epidermis) and the mucous membranes. People with the disease produce antibodies against desmogleins, proteins that bind skin cells to one another, and other proteins in the skin. When these bonds are disrupted, skin becomes fragile, and fluid collects between its layers, forming blisters.

There is no cure for pemphigus, but in many cases, it is controllable with medications.

Reply