What’s my age again?

Some people don’t look their age. Some look younger; let’s call them youthers. Others look older; we’ll call them agers. For years, scientists have sought to understand why two people can have totally different health metrics and appear to be years apart when they are the same chronological age. Researchers are refining the definition of aging to base it on biological measures, rather than just years lived. We know that one’s cumulative biological age can be older or younger than one’s birth age.

Measuring biological age

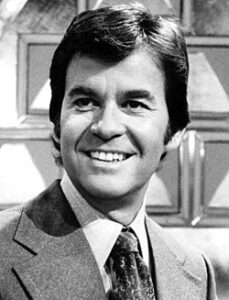

Dick Clark, pictured here in 1974, was the ultimate youther. The ‘American Bandstand’ host was nicknamed America’s oldest teenager. (Image: Wikipedia.)

One biological-age definition gaining widespread use states that biological age “represents the accumulation of damage to the body attributed to natural aging (years lived), and from specific lifestyle behaviors.” Throughout a person’s life, DNA accumulates molecular changes (i.e., mutations in DNA sequencing) that turn various genes on and off. It’s these gene mutations that determine the cellular function of body organs like skin, heart, blood, circulation, etc.

Speeding up or slowing down gene alterations determines if a person is a biologic youther or ager. We know smoking and alcohol consumption cause cellular gene alterations resulting in a shortened lifespan in different organs. In contrast, regular and consistent physical activity and various dietary habits cause specific cellular changes resulting in an increased lifespan.

By analyzing gene changes in thousands of people at a given age, it is possible to create an epigenetic clock or average pattern of gene activity at certain ages. These patterns of gene activity can then be used to categorize a person’s biological age.

For example, if a 40-year-old’s gene activity matches that seen in most other 40-year-olds, that person’s biological-age clock would be the same as their chronological-age clock. But, if the gene patterns more closely resemble those of a typical 30-year-old, the person would be a youther, i.e., they are biologically young compared to their chronological age. If the gene activity resembled that of a 60-year-old, the person would be considered an ager.

Healthspan versus lifespan

It is possible to have a long lifespan but a short healthspan, and vice versa. Someone who lived for 100 years but who spent 40 years suffering from chronic disease or disability had a long lifespan and a short healthspan. A person who lived a disease-free life and died at 55 in a car accident had a short lifespan but a (relatively) long healthspan. For most people, the ideal goal is to have a long lifespan and a long healthspan. Maintaining good health throughout life contributes to a longer lifespan. On the flip side, poor health usually shortens lifespan.

Increasing healthspan and lifespan

In one of the largest human studies to date of organ aging, scientists found that heart agers are far more likely to develop heart failure than other people of the same chronological age. At the same time, brain youthers are about 80 percent less likely to develop dementia in later years than people with average or old brains.

Perhaps the most critical finding was that organ age(s) can be changed. When you compare people’s organ ages to their lifestyles, as shown in the accompanying figure, those who smoke, drink, or eat processed meats are more prone to accelerated organ aging. In contrast, anyone who regularly exercises or eats a plant-based diet and oily fish are far more likely to have youthful organs, a longer healthspan, and a longer lifespan.

Interestingly, for menopausal women, estrogen noticeably affects organ aging. Women who use supplemental estrogen wind up with relatively youthful immune systems, liver, and arteries compared to those who don’t take estrogen.

How diet, exercise, hormones, or other lifestyle and medical options affect organ aging and biological age is unclear. Perhaps it’s genetic predisposition, lifestyle factors, luck, or the complex interplay of these factors throughout a person’s life that affects healthspan.

Youthers and agers among people who live past 90

A recent study unveiled some common biomarkers, including cholesterol and sugar levels, in people who lived past 90. This study compared the biomarker profiles of people who went on to live past the age of 100 with the profiles of their shorter-lived peers. Researchers investigated the link between health biomarker profiles and the chances of becoming a centenarian. The study included data from 44,000 male and female Swedish adults who underwent health assessments at age 64 through age 99 and were then followed for up to 35 years. Of these people, 1,224, or 2.7%, lived to be 100 years old. The vast majority (85%) of the centenarians were female.

Twelve blood-based biomarkers were included to assess inflammation, metabolism, liver and kidney function, and potential malnutrition and anemia.

Study findings

Those who made it to their 100th birthday exhibited organ health markers that resembled those who were chronologically younger. In other words, those individuals making it to age 100 had a long healthspan. For these long-lived centenarians, their biomarkers for inflammation, heart/kidney function, and sugar/fat metabolism starting at age 60 onward were lower and less erratic (did not fluctuate) compared with their cohort of non-centenarians. This suggests that changes in specific biomarkers of cellular metabolism, kidney function, inflammation, and fat and sugar use are good predictors of attaining a long healthspan and a long lifespan.

The earlier you start practicing a healthy lifestyle, the greater the probability you will increase your own healthspan and lifespan.

References

Ahadi, S., et al. “Personal aging markers and age or types revealed by deep longitudinal profiling.” Nature Medicine 2020;26:83.

Alley, D.E., et al. “Changes in weight at the end of life: characterizing weight loss by time to death in a cohort study of older men.” The American Journal of Epidemiology 2010;172(5):558.

Alvarez, J.A,. et al. “Stratification in health and survival after age 100: evidence from Danish centenarians.” BMC Geriatrics 2021;21(1):406.

Engberg, H., et al. “Centenarians — A useful model for healthy aging? A 29-year follow-up of hospitalizations among 40,000 Danes born in 1905.” Aging Cell 2009;8(3):270.

Hirata, T., et al. “Associations of cardiovascular biomarkers and plasma albumin with exceptional survival to the highest ages.” Nature Communications 2020;11(1):3820.

Horvath, S. “DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types.” Genome Biology 2013;14(10):R115. Erratum in: Genome Biology 2015;16:96.

Ismail, K., et al. “Compression of morbidity is observed across cohorts with exceptional longevity.” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 2016;64(8):1583.

López-Otín, C., et al. “Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe.” Cell 2023;186:243.

Motta, M., et al.. “Successful aging in centenarians: Myths and reality.” Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2005;40(3):241.

Murata, S., et al. “Blood biomarker profiles and exceptional longevity: Comparison of centenarians and non-centenarians in a 35-year follow-up of the Swedish AMORIS cohort.” GeroScience 2024;46:1693.

Wennberg, A.M., et al. “Blood-based biomarkers and long-term risk of frailty-experience from the Swedish AMORIS cohort.” Journals of Gerontology, Series A Biological Sciences, Medical Sciences 2021;76(9):1643.

Willcox, D.C., et al. “Centenarian studies: important contributors to our understanding of the aging process and longevity.” Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research 2010;2010:484529.

(Lead image: Promotional still from the 2008 Paramount film “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.”)

Richard Lane - 1965

When a resident of Battle Creek Michigan and younger once and then, I received my Bachelor of Science in Business Administration in 1963 from Western Michigan University . . . and In 1965 my Master’s Degree in Hospital Administration from the U of M. I am age 95 with a rather sound age-related mind and still able to drive. I have never smoked or drank alcohol or had recreational drugs. I have been, at my choice, a vegetarian for the past 63 years along with reducing intake of dairy and sugar during the past 20 years. I credit my ‘gift of years’ to Diet and Exercise. I played senior basketball up to age 90 and jogging in my earlier years. Basketball was my greatest fun and golf was my greatest pleasure. Thank you for the U of M and its publications, connections and continuing information. (Dick Lane)

(Responsively Yours)

Reply