A colossal spectacle

In two earlier Michigan Today columns about the making of The Birth of a Nation in 1914 (Aug. 17,2014) and its explosive reception in 1915 (Feb. 15, 2015) I set out to explain why many historians, political observers, and film critics consider D.W. Griffith’s Civil War, pro-Ku Klux Klan epic to be a motion picture that — simply put — just won’t go away. Throughout the 20th-century, American conservative and white supremacist groups from coast to coast have screened the film for purposes of political advocacy — often, as David Duke told me in an interview, to show what “an earlier generation had done to rid themselves of ‘outsiders.’”

In two earlier Michigan Today columns about the making of The Birth of a Nation in 1914 (Aug. 17,2014) and its explosive reception in 1915 (Feb. 15, 2015) I set out to explain why many historians, political observers, and film critics consider D.W. Griffith’s Civil War, pro-Ku Klux Klan epic to be a motion picture that — simply put — just won’t go away. Throughout the 20th-century, American conservative and white supremacist groups from coast to coast have screened the film for purposes of political advocacy — often, as David Duke told me in an interview, to show what “an earlier generation had done to rid themselves of ‘outsiders.’”

While heralded at the time of its release as a screen achievement unlike any other, the fledgling NAACP and numerous other organizations decried the film’s racist theme and its repugnant, stereotypical treatment of blacks. Protesters marched outside movie theaters and called for a ban.

This column details Griffith’s activities, personally and creatively, in the aftermath of The Birth of a Nation’s tumultuous reception. The film’s huge success with filmgoers made Griffith — at least for the time being — a wealthy man as it did Thomas Dixon Jr., the novelist who wrote the two books on which the film was based. And Griffith clearly relished the critical praise bestowed on him for his mastery of cinematic techniques. But how did the attacks on the film by the NAACP, newspaper editorialists, movie-house protesters, and black activists affect him?

Ripple effect

We know the negative reactions led Griffith to stand outside theaters and distribute pamphlets that attempted to justify his on-screen views of post-Civil War Reconstruction and the Ku Klux Klan. We also know that in journal interviews about criticism of The Birth of a Nation’s sensational thematics, Griffith seemed unwilling to offer any direct apologies for what he had brought so forcefully to the screen. Historians have speculated that that stand was derived in part from critics’ attacks that he found personally overwrought.

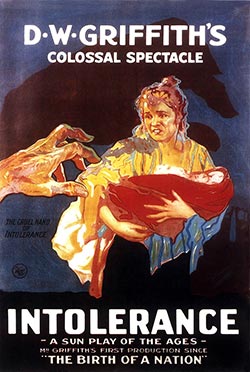

And then there is the significance of the massive, multi-storied epic Intolerance (1916) made the year following The Birth of a Nation. We are now in the centenary year of Intolerance’s release, and it deserves a look back. Critics and historians have seen in its creation an indirect ‘mea culpa’ by Griffith. The late Roger Ebert, for one, maintained that in Intolerance Griffith sought to make amends for the racist and “brutal images of blacks” in The Birth of a Nation with a follow-up film themed around prejudice and cruelty.

Intolerance’s back story

The narrative inception for the film that would become Intolerance actually occurred before The Birth of a Nation’s release. In late 1914 Griffith had begun filming “The Modern Story,” which would be one of four narrative components of Intolerance. Said to be inspired by the waning Progressive Movement of the early 20th century, “The Modern Story” showcased the social injustices among factory workers in New York City at the time. It was not a new theme for Griffith. In 1909, working at Biograph Pictures, he made a 12-minute film titled A Corner in Wheat. The plot centered on a wheat tycoon whose capitalist greed drives up the cost of bread, adversely affecting the poor, financially strapped factory workers.

Griffith employed dialectical crosscutting between the extravagant lifestyle of the tycoon’s circle of friends with that of common workers waiting patiently in a bread line. The “montage of collision” approach drove Griffith’s social message forcefully home. The plot of “The Modern Story” contained similar elements but was more complicated. A young working class husband (The Boy) and his wife (The Dear One) fall victim to a slum underworld, dominated by a corrupt overseer and a monopolistic capitalist. The Boy is sentenced to the gallows for a crime he did not commit, and The Dear One, declared an unfit mother, loses her baby to a women’s group acting to “clean up” society.

Big ideas, bigger budget

With the impending release of The Birth of a Nation in April 1915, Griffith had to put “The Modern Story” aside for several months and see to the promotion of his Civil War epic. That done, Griffith returned to “The Modern Story,” which he retitled “The Mother and the Law.” Inspired and spurred on by the great financial success of The Birth of a Nation, Griffith decided to expand the idea of human injustice and cruelty into four separate stories that span 2,000 years of history, beginning with “The Modern Story.”The remaining three stories were called “The Judean” about the religious indifference and intolerance that led to Jesus Christ’s crucifixion; “The French Story,” an account of the royalist-led persecution of protestant Huguenots in 16th-century France; and “The Fall of Babylon,” which chronicled the invasion and destruction of ancient Mesopotamia by Persian troops in 539 B.C.

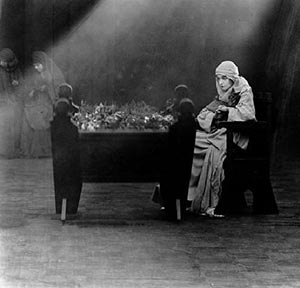

The four stories — each to be tinted with a different color — would be interwoven for a composite treatment of Griffith’s grand thesis. Bridging the flow of the stories was a poetic insert of a mother — bathed in an ethereal light — rocking a cradle. The recurring shot bore the on-screen text: “Endlessly rocks the cradle, uniter of here and hereafter. Chanter of sorrows and joys.” The lines came from Walt Whitman’s poem “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking” from the third edition of Leaves of Grass (1860). The mother represented the symbolic link between the progression of the human race and that of the eternal possessor of human sorrow.

A bold exercise

The making of Intolerance was a bold exercise in creative filmmaking. For the Babylonian story, Griffith’s crew constructed massive settings, including walls as high as 100 feet that horse-drawn chariots could top as the Persians battled the Babylonians. The scenic designs for the French Huguenot sequences were also impressive, elaborate, and costly. More than 3,000 crowd extras (paid $2 per day) filled out the cast. Estimated production costs of scenery, costuming, and actor/extra fees was $2.5 million, a staggering sum equivalent to $60 million today.

In combining the four stories (into a 14-reel, 3.5-hour release print), Intolerance’s editing structure involved more than 50 cut transitions back and forth among the narratives with the Modern, Judean, and Babylonian sequences building toward suspenseful, last-minute rescue attempts that had long been a Griffith trademark. The Dear One prays for a governor’s pardon as her husband (The Boy) stands on the gallows platform. A mountain girl rushes by chariot in a failed attempt to save her adored Prince Belshazzar from the Persians. Two young Huguenot lovers are unable to escape the deathly St. Bartholomew Massacre. As the story lines progress toward a climax, Christ is viewed approaching Calvary.

Life of the different ages

In the program for Intolerance’s premiere in New York’s Liberty Theater on Sept. 5, 1916, Griffith explained the rationale behind the composites and his unique editing structure: “The purpose of the production is to take a universal theme through various periods of the race’s history: Ancient, Sacred, Medieval, and Modern times are considered. Events are not set forth in their historical sequence or according to the accepted forms of dramatic construction, but as they might flash across a mind seeking to parallel the life of the different ages.”

Vachel Lindsay, perhaps better than any critic of the time, described the effect in the Feb. 17, 1917, issue of The New Republic: “…the days of St. Bartholomew and the Crucifixion signal back to Babylon sharp or vague or subtle messages. The little factory couple in the modern street scene called The Dear One and The Boy seem to wave their hands back to Babylon amid the orchestration of ancient memories.” But an unnamed critic was less than impressed in a Daily Variety review Sept. 8, 1916: “The effort to tell four stories at the same time makes it so diffuse in the sequence of its incidents that the development is at times difficult to follow.”

Confounded filmgoers felt the same and while Intolerance was an initial box-office success, attendance quickly waned. By 1918, to recoup some of his financial losses, Griffith was forced to separate “The Mother and the Law” and “The Fall of Babylon” into two discrete films, one a social melodrama and the other a spectacular historical epic. Each found receptive audiences.

Intolerance’s legacy

Intolerance in various forms has continued to screen since its release a century ago. It was shown out of competition at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival. In the 1980s the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) reconstructed the film at great expense — a challenging task in part due to the dismantling of the original negative in 1919-20 to achieve the single release prints of “The Mother and the Law” and “The Fall of Babylon.” Historian Kevin Brownlow has overseen screenings of the MOMA restoration, noting the achievement and lasting influences of Griffith’s original four-story epic.

In spite of (and in no small part because of) its original complexity, Intolerance is regarded as one of the greatest films in cinematic history. In 1989 in its initial year of selecting and preserving American films of lasting social and cultural significance, the Library of Congress selected Intolerance.

The film’s influence on post-Revolutionary Russian filmmakers was well-noted by Vsevolod Pudovkin, who was inspired by Griffith’s cross-cutting editing constructions and his development of historical screen epics. Pudovkin, initially a chemist, says he turned to filmmaking after seeing Intolerance. His Mother (1926), a historical drama about the abortive Russian uprising at Tver in 1905 — owes much to Griffith in both narrative familiarities and editing technique. The great French director Abel Gance — J’Accuse (1919), Napoleon (1927) — was an avowed admirer of Intolerance and Griffith’s innovative editing and camera techniques. Numerous other directorial greats from Erich von Stroheim to Stanley Kubrick have spoken of the impact that Griffith’s historical epic had on their own screen efforts.

And Griffith’s intended message in Intolerance was not lost on reviewers. An Oct. 19, 1916, editorial in The San Francisco Bulletin observed that “Griffith’s film comes powerfully to strengthen the hand of the believers in love. Overwhelmingly he preaches the lesson that no action inspired by hate can be other than wrong.”

The years after Intolerance

In 1919 Griffith joined Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin in the formation of the United Artists Corporation, a gesture aimed at giving the director-actor consortium greater creative control over the production and distribution of their own films. Although the excessive expense of producing Intolerance, combined with its commercial failure at the box office, left Griffith financially distraught, at United Artists he would have some continued success, most notably in films starring the great Lillian Gish: Broken Blossoms (1919), Way Down East (1920) and Orphans of the Storm (1921).

These films were popular with filmgoers, but Griffith continued to lose money because of the large sums he continued to pour into the production and promotion of the films. Way Down East, a melodrama in which Gish is rescued from an ice floe, was Griffith’s one major commercial success after The Birth of a Nation. In 1924, out of financial necessity, he accepted a staff directing position at Paramount Studios.

By the late 1920s Griffith’s film stature had begun to fade away following the release of a number of fairly commonplace efforts. His glory days as an American motion picture director, with more than 450 films behind him, were past. Many would claim, as they later did with Orson Welles, that Hollywood had turned its back on D.W. Griffith.

Ending Notes

On July 23, 1948, living alone in the Knickerbocker Hotel in Hollywood, Griffith was found unconscious following a cerebral hemorrhage. He died later that day.

In 1953, in recognition of his unequaled contributions to the development of film art, the Directors Guild of America (DGA) created the D.W. Griffith Lifetime Achievement Award. However, in 1999, reacting to increasing claims that The Birth of a Nation was responsible for generating “intolerable racial stereotypes,” the DGA governing board dropped Griffith’s name from the citation. DGA President Jack Shea said: “As we approach a new millennium, the time is right to create a new ultimate honor for film directors that better reflects the sensibilities of our society at this time in our national history.”

Future, as well as previous winners, would be listed as recipients of the Directors Guild of America Lifetime Achievement Award.

Timothy Anderson - 1977

Kudos to Professor Beaver for his insightful discussions of film. His comments regarding the work of D.W. Griffiths have greatly enhanced my enjoyment of and my respect for the work of this early film pioneer while putting his work and prejudices in perspective. My experiences in the South at the time of the tragedy in Memphis validates many of Professor Beaver’s remarks on the terrible burden and blindness of the South to its own history. Thank you for helping me to further understand how good men could follow such an evil path.

Reply