In English, it is often said, there are no synonyms, and it’s true. While we may be able to substitute one word for another without changing the meaning much, it is not hard to construct contexts in which one word fits fine and the other clashes. In discussions of Ovid’s tale of Acteon and Diana (as told by Chaucer and painted by Titian) the words “naked” and “nude” seem nearly interchangeable. Yet “the naked truth” is quite a different thing from “the nude truth,” and it seems silly to say “nude as a jaybird.”

Teasing out the differences between synonyms is fascinating to the word-curious; whole books have been devoted to doing so.

Sometimes they are called dictionaries of synonyms: these have an alphabetical ordering with clusters of related words gathered together and linked by cross references. Sometimes they are called thesauruses: these arranged by clusters of meanings and linked by an alphabetical index. (There’s also a dispute about the plural of thesaurus which we will pass over here.)

The first large book of this kind was called British Synonymy, published by Hester Lynch Piozzi in 1794. She was a gentlewoman of polish and learning, and her entries are little essays in nuance and discrimination. For instance, she distinguishes amiable, loving, charming, and fascinating. And affability, condescension, courtesy, and graciousness. These words take us into the world of Jane Austen, and the book helps us to understand what Elizabeth Bennett means when she tells her father that Mr. Darcy is “perfectly amiable,” or how we are to understand Mr. Collins who gushes, again and again, at the condescension of Lady Catherine De Bourgh.

The 19th century was the great age of systematic taxonomies. The periodic table not only displayed the filiations of all the known elements but also allowed for ones that might be newly discovered or synthesized. The Dewey decimal system organized libraries in ways that put related works together but allowed new books to be written and whole new subjects to be contrived.

Peter Mark Roget, an Edinburgh-trained physician, devised a system that would organize all the meanings human beings might want to express (including new ones that might come along later). These he published as the Thesaurus in 1852. It went through many editions including ones expanded by his son and grandson. A generation or two ago, high-school graduates received copies of Roget’s Thesaurus on the principle that its contents would enlarge the mind (or at least enhance prolixity in vocabulary).

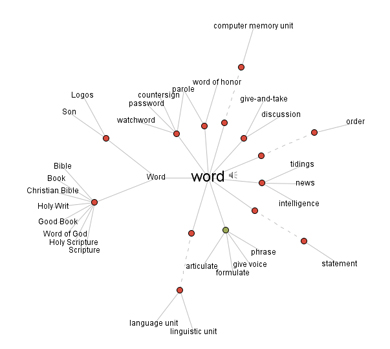

A synonym map from the visual thesaurus.

Now, in the age of the internet, we have many such works including the Visual Thesaurus. (Disclosure: Ben Zimmer, the “executive producer” of this resource, is a friend of mine.) You can see what the array of meanings are for a given word, but you can also see a map of somebody’s words—for instance, Holden Caulfield in the late J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye reveals a network of associations. And you can even see how Holden’s meanings connect him to Mark Twain’s Huck Finn.

Piozzi’s Synonymy arranged related words along a one-dimensional trajectory. Roget’s Thesaurus gave us two dimensions by arranging synonyms from literal to figurative—for instance, bare to birthday suit.

Now we have a three dimensional thesaurus: The Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary. Here meanings are displayed in clusters showing their history. For example, people in Shakespeare’s day could be naked but not until later could they be nude. The weighty two volumes of the Historical Thesaurus will have a transforming effect in showing us what possibilities people in a given day had for expressing themselves.

Kimberly Smith Albrecht - 1979

Dear Dr. Bailey, Yes, once lit, the flames of bibliophilia never extinguish… dim… fade… diminish… ebb…

Reply

Lewis Dickens - 1964

Dr. Bailey,

For years I have wanted to talk with you because a young lady named Sue, I believe, told me years ago about you and your work so what a pleasant surptise it was to see your article this morning.

I’d like your impression of a taxonomy that I created for Architecture, Engineering and Construction… a domain full of confusion.

If you could look at this recent article that was published I would appreciate it very much.

http://www.aecbytes.com/viewpoint/2010/issue_50.html

I would love to hear your response.

Bill Dickens

Reply

Frank Povah

Thank you, Professor Bailey, for supporting the argument that access does not have precisely the same meaning as gain, enter, reach, obtain, attain, get, into, onto, board, embark, climb and no doubt a host of other words that don’t immediately spring to mind.

Reply